Disappearing Bawa

View(s):A new book by David Robson and Sebastian Posingis reveals that Sri Lanka is in danger of losing a rich architectural heritage

The Jayakody House, Colombo. Pictures courtesy Sebastian Posingis

By Smriti Daniel

It might seem to the world that Geoffrey Bawa’s legacy is assured, but a new book by his most well-known biographer asks whether enough is being done to protect it. In Search of Bawa with text by David Robson and with photographs by Sebastian Posingis, sees Robson return to a subject he knows intimately, but even as he spends several pages on Bawa’s remarkable life, he also highlights how over a decade after the architect’s death, Sri Lanka is in danger of neglecting the rich, architectural inheritance Bawa left the land of his birth.

The idea for the book came from Posingis, who says it was while driving with Robson around Colombo and looking at Bawa’s architecture, that it struck him that many buildings existed that were by the architect but never associated with him, as well as others that claimed to be by Bawa but were not. “My first thought was that a “Bawa app” for the phone would be great, with GPS, tons of information, audio and suggestions of nearby properties,” says the photographer, admitting wryly that,“I still think it is a worthwhile project but as I am not much of a tech guy and more interested in books, I thought a small publication would be the next best thing.”

Priced at Rs.3,400, In Search of Bawa is meant to be affordable and portable, making it suitable for the libraries of students and the suitcases of travellers, but its real interest may be in its systematic survey of what remains of Bawa’s work. Posingis and Robson travelled across Sri Lanka, and found that many of Bawa’s buildings were in a state of disrepair, had been reconstructed beyond recognition or were even in danger of being demolished.

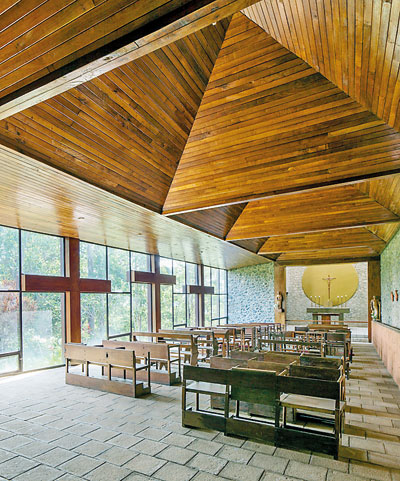

When he began taking the pictures, Posingis knew he was most interested in images that were honest, rather than beautiful – though from his results it is clear that the former didn’t rule out the latter. But to his disappointment, the photographer sometimes found there was not much left for his camera to record. “Some of the pictures I have admired for years just did not exist anymore, either due to alterations or simple obstructions such as trees or other buildings. Some of the black and white pictures of the nuns at the Chapel in Bandarawela, The Strathspey’s Estate Bungalow or the classic image of the State Mortgage Bank cannot be taken anymore.”

The Nazareth Chapel of the Good Shepherd Convent, Bandarawela

The book’s appendices dedicate several pages to Bawa buildings at risk, those that have been transformed and those that are lost to us forever. “To a degree Geoffrey Bawa has become a cliché,” Robson tells the Sunday Times over a Skype call, referring to the near ubiquitous popularity of the architect’s work. Robson notes however that there is a contradiction here, despite Bawa’s growing legend, “his buildings are being treated very badly, and they are disappearing very quickly.Unfortunately quite a number of his buildings have now been altered or been destroyed.”

But it isn’t all bad news. A photograph of the library at the Ruhuna University Campus is one of the highlights of working on this book for Robson. He says Posingis has taken what may be one of the first pictures of the interior of the library ever to be published. In Posingis’ picture, the library’s double-height reading rooms are framed by bookshelves and rows of windows that bring the light flooding in. The pleasing geometry of the reading halls is reflected in the paneled ceiling. It is very much an inhabited, well-loved space, as its architect intended it to be.

Robson notes that subsequent renovations and extensions to the university have been done with great care so as to add to rather than detract from Bawa’s original design. Another great discovery for the author was the Ratna Sivaratnam House off Buller’s Road, where the son of the late owner had painstakingly renovated the house. “When I saw it in 2000 it was in very bad condition, but they have done a marvellous job of bringing it back up,” says Robson. A similar effort returned The Raffel House to its original glory.

There are lessons to be learnt here about how a conservation effort is successful. Robson believes that buildings do not stand still. “If you are going to conserve a building you have to have a use for it,” he says, pointing to the work of the National Trust in Britain as a working model for this approach. “Inevitably in preserving a building, there will be changes.”

One of the biggest success stories for Robson has been the conversion of Bawa’s office into the Gallery Café. “It is an example of a completely new use for a building but somehow it preserves the spirit of the place. It is still essentially the building Geoffrey designed in 1962,” says Robson, pointing out that as a result, so many thousands have enjoyed it. He minces no words when describing another effort by the same owners though – “If you take the hotel called The Villa at Bentota, I think they have added buildings to the extent that it has completely ruined the character of the original.”

For the author, all this points to the need for a more considered and comprehensive approach to preserving Bawa’s buildings. For Sri Lanka, this would also mean investing in a source of tourism revenue as interest in Bawa’s work brings his fans flocking to these shores. Says Posingis: “I hope this book opens up a wider conversation about the preservation of buildings in Sri Lanka. It’s frightening to see the speed at which buildings disappear here, especially in Colombo.”