Back to life brick by brick

Restoration of the magnificent Abhayagiri dagoba, a project Nilan spent much time on

Nilan Cooray understands how cruel time is to beautiful buildings.

He is no stranger to slow erosion by Sun, wind and rain; the shifting earth and the tunnelling roots that prise apart brick and mortar. But as one of Sri Lanka’s foremost conservation experts, Cooray is trained to look past leaks and crumbling plaster to see things as they were – and then to return them to that former glory. It is a rigorous art that demands an understanding of many different fields, but Cooray has had decades to develop his craft. The current Director of Conservation for the Cultural Fund, Cooray sat down for a far ranging interview with the Sunday Times this week.

Soft-spoken and patient, 53-year-old Cooray tells me that his “academic father” is S. Roland Silva, widely considered one of the great Asian experts in the conservation of historical monuments and sites. But Cooray’s connection is more personal than that – he credits Silva with propelling him from a career in architecture to one in conservation. In fact, it was while Cooray was a student at the University of Moratuwa, (from where he received his B.Sc, M.Sc and a postgraduate diploma in architectural conservation) that he heard a lecture by the former head of the Department of Archaeology. He was so inspired that Cooray followed Silva to the Cultural Triangle Project, where he says he learned some of his most enduring lessons about conservation.

First as a project manager, then as the assistant director, Cooray was part of the team that laboured to restore the World Heritage Sites of Anuradhapura, Sigiriya and Kandy under UNESCO’s campaign to safeguard the Cultural Triangle of Sri Lanka. Not only did this involve becoming well acquainted with World Heritage standards,but for a few months it also required that Cooray climb up and down Sigiriya’s 1,200 steps at least thrice a day. At the top, the now iconic water gardens lay in ruins, their conduit sand ponds packed with silt. Close by, the Dambulla paintings demanded attention, as did a dozen other sites.

“We were learning how to carry out mega-projects for the first time,” Cooray says looking back. “These were the biggest heritage programmes we had undertaken in this part of the world, and it was a steep learning curve.” Beyond the technical challenges of the task, Cooray says they had all the issues of a sometimes recalcitrant workforce to deal with. But in the middle of this, he would find moments of great personal significance. “When you excavate a monument for the first time, when you are touching it, you know you are among the first to do so after centuries. That gives you a feeling of connection with the people who made it, who lived in it so long ago. For me it has been a privilege to work on these sites.”

Yet, in its everyday manifestation, Cooray’s work is a catalogue of mundane obsessions. Between 2003 and 2009, much of his focus lay on restoring the Abhayagiri Dagoba. The structure dated back to the 1st century BC and was once over 100m high. Today, it is celebrated as one of the great constructions of the ancient world, rivalling the pyramids of Giza in scale.

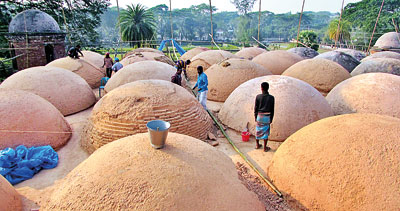

“It is the second largest brick monument in the world and so our challenge was to make the right kind of bricks,” says Cooray, explaining that the ancient technology no longer existed in Sri Lanka and that the department had been using the standard bricks introduced by the British in all their projects. Turning to the brick-makers of Bangladesh, the Sri Lankan team built a kiln in Anuradhapura that could produce bricks that were thin and long (approx. 16 inches x 8 inches in size and only 2inches deep) in keeping with the kind preferred by the ancients. “They were very thin compared to the modern brick, but the surface area is more, and so the compression strength is more,” he explains.

Another project for the team was the development of a special kind of mud mortar with the National Building Research Organisation (NBRO). The final recipe was a blend of some very uniquely Sri Lankan ingredients. Says Cooray: “Just using mud between the bricks meant that it would be washed away, but we didn’t want to use cement. So as a kind of compromise, we developed a mixture of lime and paddy husk, and then added ant hill clay and tile dust. It was a ground-breaking mixture that worked so well that we used it for the stupa and it is now being used in other monuments as well.”

When the Abhayagiri project ended, Cooray went on to work on a particularly unique effort – the Bawa Trust’s relocation of the Ena de Silva house. This early work by the iconic architect was in danger of being demolished, and with the land it stood on in Colombo 3 having been sold, there seemed few options. Then the Trust decided to disassemble the entire structure and reassemble it on a plot off Bawa’s gardens in Lunuganga.

Nilan at work in Bangladesh

Cooray and his team brought to this task a staggering attention to detail, producing hundreds upon hundreds of glass drawings that located every element of the house within its context – he numbered the wooden slates in each latticed window, and the boulders embedded in the interior courtyard. Neither did the rough granite slabs or the small panels on the parquet floors escape his attention. Cooray then directed the team who, working from the roof down, rapidly broke down the house and trucked it in pieces off to Lunuganga. When the house was rebuilt, Cooray’s detailed drawings and numbering system allowed them to place each element exactly where it used to be. The numbers are still visible in parts of the house.

Cooray’s work has also taken him out of Sri Lanka to projects in locations such as Myanmar, Netherlands and Nepal but his most recent project took him to Bangladesh where he was asked to help conserve the Bagerhat and Paharpur World Heritage Sites, Mahasthan (on the Tentative List of World Heritage Sites) and the Kantaji Temple.

He is perhaps most pleased with the work he did on the Shait Gumbad Mosque in Bagerhat. “It was the first time I had worked on an Islamic building,” he says, explaining that Shait Gumbad is one of the largest ancient mosques in this part of the world, and was constructed totally out of bricks. Though Shait Gumbad literally means 60-dome mosque, it in fact has 81 domes. On site, Cooray found he had to contend with additional columns, heavy leakage, and crumbling terra cotta decorations. Again, restoration hinged on getting the details right – this time it was hunting for gargoyles or water spouts that would allow water to drain off the roof of the mosque.

However, it requires more than experts like him to bring a monument fully back to life. Changing times and a grimmer global economy have made Cooray an advocate for rethinking not just how, but why we conserve.

“The earlier theory is that we would conserve a building and turn it into a museum or public space but that way a building is unlikely to generate enough funds for its own maintenance.” The venue in which our interview takes place – the former asylum now known as Independence Arcade – is a perfect example of how such efforts could be made sustainable, says Cooray.

But then he pauses, and pointing to a column says that real conservation work is exacting and every effort is made to keep original fittings, materials and ornamental structures – something he is not sure was done here. “For instance, they have used cement instead of limestone,” he points out. The former sets in a day, and the latter takes up to six months to harden, explains Cooray, but limestone, much better suited to Sri Lanka’s climate, will still be holding strong long after cement has started to crumble.

Restoring the domes of the Shait Gumbad mosque in Bangladesh

This is the kind of detail Cooray will be paying attention to in his upcoming projects in the North and East of the island, where he says restoration work on the fort at Trincomalee as well as buildings in the island of Delft will begin later next year. Right now, they are very much in the early stages, but Cooray is filled with the anticipation every new project brings. He laughingly compares his profession to that of doctor, where “the monument is my patient.” Says the conservationist: “We have to understand that real causes for the deterioration of structure, and that is the most challenging task.”