News

Stiff winds hit Mannar Island wind turbine project

Gale-force winds of criticism are buffeting the proposed wind-turbine project of the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) on Mannar Island, known for its unique eco-systems.

All environmentalists are in total agreement on the need for Sri Lanka to make use of wind power, which is an environmental-friendly renewable source of energy, but controversy is creating turbulence about the proposed installation of more than 50 wind turbines on Mannar Island.

In the eye of the storm is the ‘Study of impact on local and migratory birds from the proposed wind farms in entire Mannar Island for the submission to the Asian Development Bank and for subsequent clearance’ put out in May this year, copies of which were distributed at a media conference on September 21.

A four-member panel of powerful environmentalists, while reiterating that they are not opposed to wind turbines, however, expressed serious concerns about their ‘positioning’ on Mannar Island. According to them the wind turbines would be in the flight pathway of a large number of migratory birds and they are adamant that the study is “flawed”. They also charge that due approval processes have not been followed. (See box)

A stronger and wider argument against placing the giant windmills with their blades making an unpleasant and constant whooshing noise on Mannar Island — with Adam’s Bridge National Park to one side and Vankalai Sanctuary to the other, making it a critical area for protection — came from a research scientist who knows the area like the back of his hand.

It is not just a “no, no” from him but also a feasible solution. “Avoiding the Mannar Island completely, the wind-turbine project should go farther south, closer to Silavaturai and Arippu, to a less environmentally-sensitive area with equally strong winds to provide the country with the benefits of wind-energy and the local community more jobs,” said Dr. Sampath Seneviratne, Research Scientist in Evolution Molecular Biogeography and Senior Lecturer in Zoology at the Colombo University, adding that then it would be a win-win situation for all.

Research Scientist Dr. Sampath Seneviratne

Dealing with some of the concerns over the study, he said that the raw data which have come forth from the study are good, for an efficient and qualified team headed by Prof. Devaka K. Weerakoon and including himself had fanned out across Mannar Island, spent long hours in the field, from January 2014 to April 2016, and gathered good data, working within the terms of reference decided by the CEB.

The need of the hour is to analyze this data thoroughly, he says, underscoring that the data do not show a clear “black and white pattern” about the wind turbines being in the flight pathways of migratory birds.

Drawing detailed sketches, he explains to the Sunday Times in a three-hour interview on Tuesday, not only the migratory flyways, which indicate that this is not the worst consequence of the wind turbines but also the colossal harm on the ecology which would have a gargantuan and disastrous impact on the habitat of both migratory and local birds as well as on all other wildlife.

What is a major worry for Dr. Seneviratne is that the turmoil caused by the wind turbines would have a huge impact on the “marketplace” that is Mannar Island and its environments within the Greater Palk Bay Marine Ecosystem. And he should know what he is talking about as he as a study-member on birds had recorded rare bird-sightings including the Brown Noddy species breeding at Adam’s Bridge, the Bar-headed Goose in Vankalai and numerous other species breeding throughout the year.

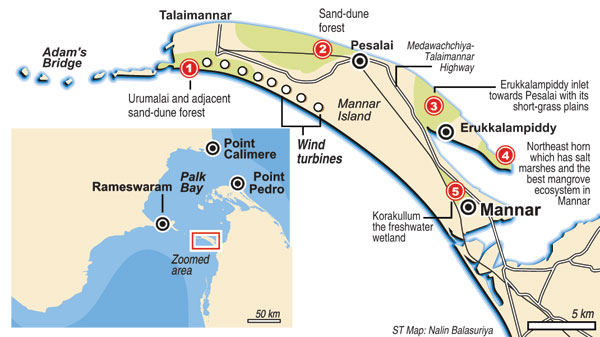

Before looking at the migratory flyways, he stresses that Mannar Island and its surroundings are a big wetland and all those birds which pass through the Palk Bay use it as a feeding, breeding and nesting ground. The island includes: Urumalai and its adjacent sand-dune forest; relatively undisturbed sand-dune forests of the northern shore; Erukkalampiddy inlet towards Pesalai with its short-grass plains; the northeast horn of the island which has salt marshes and the best mangrove ecosystem in the whole of Mannar; and Korakullum, the freshwater wetland. (See graphic)

Satellite data of four birds which have radio collars clearly indicate that the whole area encompassing Point Calimere and Rameswaram on the Indian coast and Sri Lanka’s Adam’s Bridge, Mannar Island and Jaffna peninsula is used as the primary feeding and breeding grounds by both migratory and local birds which would be greatly disturbed by the wind turbines. The birds would not know the man-made boundaries of this big wetland.

“The wind turbines will cut through this very productive ecosystem which is an inextricable part of the Greater Palk Bay Marine Ecosystem which is sandwiched between Sri Lanka and India,” says Dr. Seneviratne, pointing out that some of the essential areas for migratory birds to feed, breed and nest are the northern shores of Mannar Island.

Citing the example of the tidal mudflats, which turn into feeding grounds for the birds during low tide and wash in the tasty morsels of various invertebrates during high tide, he says that if it is disrupted the next available feeding ground would be the western shore of the Jaffna peninsula. Harm to the Mannar Island mudflats will have a snowball effect, tilting the delicate balance, he is quick to point out, adding that a large number of birds will not die by getting slashed by the blades of the wind turbines but because the destruction of the mudflats will denude the area and cause starvation en masse.

Looking deep into the Mannar Island wetlands, this Research Scientist says that although the mix of water and land is what the wetlands are all about, the fluid or hybrid nature of the area caused by the constant ebb and flow is what makes it special. A ‘good’ wetland, as is now found on Mannar Island, consists of intermediate tidal plains, undisturbed land and good water. Mannar Island has this and much more, 50sqkm of tidal mudflats backed by good forested patches. Of course, the forested patches are not like Sinharaja but typical of the area’s climate which is scrubland.

The very fact that the Indian coastline has been de-forested adds more weight to the argument for the preservation of Mannar Island in its pristine state, making it a haven not only for birds but also for other wildlife. The shallow patches, hidden around the island exposed to ultra-low tide are a paradise for flamingos, while for those birds with short legs it becomes a staging area after a long flight, with the soft soil being “a rich soup” of invertebrates for birds with different lengths and shapes of beaks as well as varying leg lengths. The land, if concreted, will take away the refuge of birds during high tide, as well as their breeding and nesting grounds.

Mannar Island is sensitive, he keeps repeating, adding that this is why it should be left alone and safeguarded against wind turbines as well as other so-called development intrusions and human encroachment.

Dr. Seneviratne then deals with the thinking that the wind turbines on Mannar Island would disrupt the flyways of the migratory birds. There are two migratory flyways, to avoid the winter and return home through the spring migration according to him:

· The Eastern Flyway – Originates in far eastern Russia and eastern China and kisses the eastern shores of Asia into eastern Asia and Australia. However, some birds such as ducks and shorebirds from northeastern Asia including Siberia fly in a southwest direction into South Asia. As they near the Himalayas, because they cannot overcome (except the species of the Bar-headed Goose) the Himalayan wall, they fly down towards Bangladesh and onto the eastern shores of India and Sri Lanka.

· The Western Flyway – Birds in Europe and western parts of Asia fly down to Africa through Gibraltar and the Mediterranean. Some of them, however, fly eastward and come through Pakistan to the west coast of India and Sri Lanka.

When they come to India, for them, the south of India and Sri Lanka act as a funnel, and they stop somewhere as these are the tropics. They do not go beyond Sri Lanka, as there is a huge mass of sea around Antarctica.

Therefore, the migratory pattern is North to South and the spring migration back is South to North. Mannar Island, however, is on the East-West axis. This is why there is evidence that a majority of migratory birds coming down along the Eastern Flyway make landfall on the Jaffna peninsula and not Mannar Island which is 14km away on the wrong plane for them, while those coming on the Western Flyway hit Colombo. “There is, however, some migration along Adam’s Bridge but mostly by forest birds,” he says.

Quoting extensive studies done by Birdlife International on wind turbines, Dr. Seneviratne says, the primary issue is not direct fatalities but the deafening disturbance which will make the birds avoid the area and go elsewhere. So when there is an impact of these wind turbines on the whole of Mannar Island, the birds will have no place to go for feeding, nesting and breeding which would cause major displacement.

| Initial collision risk assessment done “Based on the vantage point survey data, a collision risk assessment has been performed. It should be noted that this assessment has been made on a limited data set and therefore should be considered as preliminary risk assessment. Based on this analysis the key species that could be at risk of collision with the wind turbines include Northern Shoveler, Painted Stork, Spot-billed Pelican, Little Cormorant and Whiskered Tern,” states the Executive Summary of the Study by Prof. Devaka K. Weerakoon commissioned by the Ceylon Electricity Board. “The four main impacts on avifauna due to wind power development have been identified based on experiences in other countries and Sri Lanka. These include collision, displacement and disbursement, barrier effect and habitat change and loss. A range of mitigation measures have been proposed. These mitigation measures must be carried out to ensure that the potential negative impacts due to the proposed project are minimised. It is extremely important that the project establish an independent monitoring mechanism for the operational phase to assess the actual impact on avifauna as well as the adaptive changes that should be effected to mitigate the negative impacts on avifauna,” the study urges. It adds: “Based on the findings of the present study, the site selected for the proposed wind farm poses a significantly lower risk of avian collision as the site comprises habitats that do not support a rich species assemblage or high densities of birds or bats. Further, the species richness of birds was found to be relatively low during the period when maximum power generation (80% of the power will be generated during the period May to October) is expected to take place. Finally a suite of mitigation measures has been proposed to minimize the negative impacts that may arise from the establishment of the proposed 100 MW wind farm along the southern shore of Mannar Island.” |

The conclusions arrived at on the data are faulty  Wayamba University Senior Lecturer Sevvandi Jayakody and Young Zoologists’ Association President Parami Vidyarathne “The methodology of the study is flawed.” This is what the four-member panel of environmentalists comprising Wayamba University Senior Lecturer Sevvandi Jayakody, environmental lawyer and Senior Instructor of the Young Zoologists’ Association (YZA) Jagath Gunawardene, YZA President Parami Vidyarathne and Uditha Hettige, Chief Instructor of the YZA’s Bird Group told the media on September 21. Explaining that the wind turbines will disrupt the pathway of the migratory birds, Ms. Jayakody said that there should be a scientific study to map the pattern of bird-migration which changes over time, for then only can be determined whether there is major or minor harm. One of the seven objectives of the study, she says, is to understand which migratory birds come to the area, their migratory patterns and also the reasons for such patterns. Anyone who is studying migratory birds would know that a majority of them fly-in at night. This is why it is essential for data on migratory birds to be collected both during the day and the night. The study, however, has collected data only from 6 in the morning till 6 at night, which would not produce accurate data. Echoing similar concerns, Mr. Hettige said that a large number of birds of certain species such as widgeon (50,000) are recorded as having migrated in 2011 or 2012 to Sri Lanka but the study does not report these species. Even though the study claims that it uses a ‘collision risk model’, the researchers do not have enough data to compare them. “The sampling is wrong and so the calculation for the end result is wrong. Instead of doing proper calculations, the team has manipulated the data to show that there is no difference between the migratory and non-migratory seasons,” he alleged, stating that the study seems to be emphasizing that the area is scrubland and not valuable, which is wrong, for in that arid-zone environment that is the climax vegetation. Mr. Gunewardene, meanwhile, highlighting a point of law, said that all projects within a mile from the border of a National Reserve, in this instance the Adam’s Bridge National Park, need permission from the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) under Section 9A of the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance (FFPO). But such approval has not been sought from the DWC, instead the Coast Conservation Department (CCD) has given approval.  Environmental lawyer and Senior Instructor of the Young Zoologists’ Association (YZA), Jagath Gunawardene, making a point while the Chief Instructor of the YZA’s Bird Group Uditha Hettige looks on. Pix by Indika Handuwala “The CCD is granted power to approve a project being done in a coastal area under the Coast Conservation Act. It can get an Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) Report or an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Report but the first does not require public comment and objections. However, the FFPO requires such opinions to be sought from the public,” he said. Referring to the two-step approval process, Mr. Gunewardene said that the report needs to be approved by the CCD and also an advisory body of the CCD. The advisory body must review the report for 60 days but this has not been done. Even if it was done, there are doubts as to whether it would be able to see the impact this project would have on wildlife because those on the advisory body are not experts on wildlife. “Moreover, the DWC has just given a conclusion indicating that there are no issues with the proposed windmills but this is inadequate. It is totally wrong for the DWC to bypass its own legal procedures and give such approval to other institutions. The DWC needs to review the reports in a similar two-step process – studying it by itself and then submitting it to an advisory body, neither of which has been done,” he added. Telephone calls by the Sunday Times to get a comment from the Ceylon Electricity Board’s Environment Unit elicited no response. |