News

Thirsty for water and justice

Man-made disaster: The drained out Kukulkatuwa Tank Pix by Indika Handuwala and Sarath Siriwardene

Water has always been a scarce resource for people living in far-flung drought prone areas in the Hambantota and Monaragala districts, but in spite of being familiar with the inhospitable nature of the land, thousands of people in these areas are reeling under a severe shortage of water.

For several weeks now, the daily lives of residents of remote villages around Kataragama and Kirinda revolve around their quest for water, many staying up all night hoping the taps that have run dry will miraculously bring water or the occasional water bowser dispatched by the Water Board will come their way. While finding water for drinking and cooking purposes take precedence over their other daily requirements of water, the villagers’ main livelihoods including cattle rearing and farming have also been adversely affected, plunging their meager incomes even lower.

T. Madhushanka (35), a resident of Gaminipura in Kataragama tends a herd of around 60 buffaloes and drives the herd five kilometres to get them to the closest water body. The water in the Kukulkatuwa Tank the lifeline of around 100 families living in the village was drained in May this year with the assurance that within two months renovation work on it would be completed, but five months on, barely any work has been done to dig up the residue of mud and stone collected over the years. The tank, known as Dosar Wewa, provided water to nearly 100 acres of paddy land as well as coconut and vegetable cultivations but today what remains is just parched earth across which Madhushnka drives his herd of buffalo.

“The animals suffer as much as humans due to the lack of water. They have little food and water and in turn their milk supply has dropped sharply. Had the tank not been emptied, we would still have had some water in it despite the drought,” he said.

Madhushanka, the second in a family of four says his income has suffered as a result. “Some of the animals are sick and don’t produce enough milk and without a proper diet too the milk supply is low. I used to collect about 75 liters of milk a day prior to the drought but now it has dropped to around 20 liters,” he said.

The ubiquitous curd sellers who line the main road in Tissamahrama are testimony to the dwindling milk supplies. S. Kamalawathie says they produce only around 20 pots of curd a day as opposed to around 40 in the past due to the short supply of milk.

Two of the villages worst hit by the water shortage in Kataragama are Sandagirirgama and Mahasenpura, both of which were provided pipe borne water in the 1980s but for weeks now, it’s only the hissing sound of air that comes when they open the taps.

“Those of us who can afford it get down a bowser to fill the tank. A large bowser of 5000 liters of water costs Rs 2000 while a smaller one of 2000 liters is Rs 1000. We buy bottles of water for drinking. Now, selling water is big business,” said Madhushanka Gihan, a resident of Mahasenpura.

In the village of Sandagirigama where around 225 families live, the taps have been dry for over two weeks. “We have complained to the Water Board office in Kataragama and we have been told that new water lines are being laid out and the shortage of water would be resolved soon.

It’s an excuse they have heard many times over the years and have little faith in, said D.K.Sriyalatha. However, water or no water; these villagers get a monthly bill.

Parched land: Destroyed coconut plantation

The severe drought has also taken its toll on coconut plantations and rows on rows of dead or dying coconut trees can be seen. S.G.Karunaratne who looks after a small coconut planation consisting of around 70 trees says at least two water bowsers are brought to the plantation each week to water the plants. “This is the worst situation I have experienced in at least 20 years,” said the 61-year-old Karunaratne. “Had there been water in “Dosar Wewa”, the water could have been released to the canals,” he said.

The quarrel these villagers have is not with nature but with the lackadaisical attitude of government officials and elected representatives who have largely ignored their plight. Desperate for help, instead of turning to government officials, villagers often turn to the Chief Incumbent of the Kirivehera Raja Maha Viharaya Ven. Kobawaka Dhamminda Thera for solace.

“I have hired backhoes to help people to dig canals and clear some of them so they can draw water from whatever source available,” Ven. Dhamminda Thera said.

“The problem of water is a perennial one in this area but what we need is a permanent solution to this problem because every year this cycle is repeated,” he said.

Further away, in the village of Hajjiyargama in Kirinda, the story is almost identical. Here in the village of around 100 residents, they too complain how the tap lines have been dry for nearly a month.

K. Irangani is angry that their plight is being neglected by both the authorities as well as area politicians. “We get water bills but there is no water. Having a bath is a luxury. It’s an uphill task to provide water to the children each morning for them to wash them before they head to school,” she lamented adding that many schools in the area too are without water.

Madhushanka Gihan

A water tank with the capacity to hold 30,000 gallons of water which provided supplies to the villages in the area since it was built in 1987 lies abandoned for the past five years. A leak in it had made officials abandon it and now the water is pumped from a tank at Yodakandiya nearly eight kilometres away. “If this tank was repaired and the water was provided from here, we would not be facing this problem,” W.A.Piyasena a resident of Hajjiyargama said.

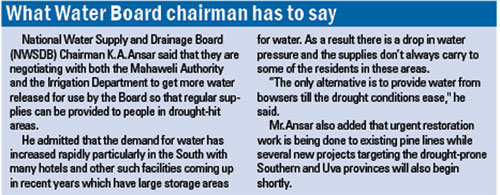

Most villagers here also alleged that the water supply to their homes is being compromised to provide water to the large number of hotels in the area, many which have come up in recent years.

“The hotels have sumps that collect the bulk of the water supplies for their use so the water pressure is too low to carry the water to our taps,” Piyasena said.

In the outlying areas of the Yala National Park, animals too are feeling the heat. With water bodies fast shrinking, crocodiles in particular have begun invading both the Tissa Wewa and the Manik Ganaga.

“People can no longer go to these places to bathe due to fear of crocodile attacks, “K.Irangani of Hajjyargama said.

The well laid out roads, grand buildings and plush hotels that line the road from Hambantota to Kataragama hide the real face of suffering of the people who live in the interiors of these areas. With drought and water shortages a regular occurance years of neglect by government authorities and failure by successive government to provide a permanent solution to their “water problem” mean the villagers have no option but to live in the harshest of conditions depending only on the change of heart of the weather gods to ease their suffering.

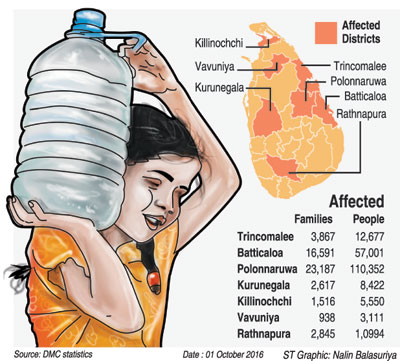

| Bowsers and storage tanks and hotline to address water crisis By Anushiya Sathisraja The Disaster Management Ministry has stepped into to assist people by setting up temporary tanks while a 24 -hour hotline, ‘117’ has been introduced for any assistance related to the water shortage, Disaster Management Center (DMC) Assistant Director Pradeep Kodippili said. An official of the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) said that under the Mahaweli Development Programme, a substantial amount of water has been diverted from the wet zone area of the Mahaweli basin to the dry zone basins. “These include reservoirs in Matale, Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, and Trincomalee districts in the dry zone,” he said. “A country is considered to be severely affected by water scarcity if the withdrawals exceed 40 per cent of the total supply,” he said adding that at present the districts in the dry zone share more than 75 per cent of the water withdrawals. The Kalutara district also been affected due to the drought with scarcity of drinking water being a major problem.  Help on the way: Boswsers carrying water and lorries carrying storage tanks are being sent to affected areas, say officials

|

K .Irangani: The water bills still come

A water tank that can hold 30,000 gallons of water lies abandoned for the past five years depriving residents of precious water

Big business: Come buy my water

(With additional reporting by Janath De Silva and Rukman Ratnayake)