News

Refugees’ welcome mat has holes

The houses that the refugees live in Talaimannar. Pix by Indika Handuwala

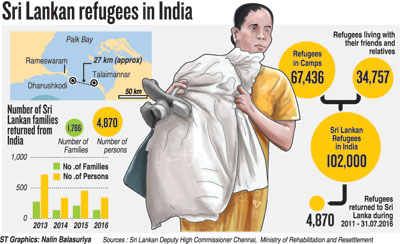

Increasing numbers of Sri Lankan refugees are returning from South India but the government has run out of money in essential programmes to help them rebuild their lives.

More than 550 refugees have returned to Sri Lanka this year to date, almost 20 per cent more than the total for last year. Most of them are settling in Jaffna, Kilinochchi, Mannar, Trincomalee and Kandy.

The Ministry of Rehabilitation and Resettlement asserts the government is encouraging refugees to return to their homeland but the practical back-up for this policy is inadequate.

Most of those returning to Sri Lanka have no homes as their dwellings were destroyed in the war.

Frank Vellachami, 37, who left came back to Sri Lanka with his family in the last week of September and settled in Talaimannar, said the whole family had been crammed into a single-room house in a refugee camp in India.

“It was the main reason for us to leave the refugee camps, and we wanted our children to live in their homeland but here our misery continues as our house is in a dilapidated condition,” Mr Vellachami said.

Former refugees are also finding it difficult to support themselves. “Before fleeing Sri Lanka we went fishing to earn our living. But we find our boats have been destroyed, which makes it hard for us to earn a living,” said Vellachami Jesuraja, 42, who lived in a refugee camp in India for 10 years.

Periyasami Kanakarasa, 40, who also returned from India, admitted that his family is facing a challenge with housing and finding jobs. “We informed the local District Secretary of our arrival and asked for help. Though they have assured they will provide help the process is delayed and is causing us misery,” Mr. Kanakarasa said.

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), which facilitated the return of the refugees, providing them with free air tickets, transportation fares and a reintegration grant, says the first three to six months is the most difficult period for returnees.

Jennifer Jesuraja

“Many of the individuals are returning to their places of origin after 10 to 20 years in refugee camps. Access to adequate housing, water, education, health and viable options to earn a living must be promoted by the government. This can become the key deciding factor for the voluntary return of Sri Lankan refugee residing elsewhere,” a spokesperson for UNHCR said.

Young returnees who were educated in India find it difficult to have their certificates recognised by higher education bodies and employers.

Jennifer Jesuraja, who was educated in India to a level equivalent to Sri Lanka’s GCE Ordinary Level, has to spend another two years in school here to gain an O-Level. Another girl, Sahaya Meclin, who had been top of her class in India and holds an Indian diploma in computer science, is unable to find work appropriate to her qualifications.

“I cannot even apply for higher studies as converting my certificates to Sri Lanka is tough. Now I am looking for job of any kind, be it skilled or even unskilled as it is tough to survive without a job,” Miss Meclin said.

The Ministry of Rehabilitation and Resettlement said returning refugees could apply for support through programmes that benefit all war victims, including Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) and war widows: there was no special government-funded programme to address the returnees’ needs.

“All returnees who face difficulties over housing can apply for [support under] the welfare programme for war victims,” the Secretary for the Ministry of Prison Reforms, Rehabilitation and Resettlement, V Sivaganasothy said.

“If the returnees’ houses are damaged they can contact the Government Agent of their area who will provide money for this.”

Officials admit, however, that funding allotted to housing schemes for war victims has been used up, which means refugees have to wait months longer for help.

The Government Agent of the Mannar district, where many of the returnees have settled, said many of them had applied for funding to rebuild their homes. “The people have to wait for the ministry to announce new programmes to address their needs as the funds allocated to us have already been used,” the GA, Mr. M.Y.S. Deshapriya, said.

The ministry also disclosed that there is no specific employment program to help returnees find jobs with their Indian educational qualifications. “All programmes cannot be set up overnight. We have talked to the universities and Education Department to solve the problems regarding the [recognition] of returnees’ educational

certificates,” Mr. Sivaganasothy said.

To address unemployment among the refugees, the ministry has a programme through which applicants will be given help for self-employment through a Rs 100,000 grant for each family.

| Talaimannar hums again as refugees return

The village is known for it close connections with India, mainly in trade, and Talaimanar residents recall the old times, when they used to get goods from India cheaper than they could buy them in Sri Lanka. S.H. Ameen, who runs a hotel now at Talaimannar, revealed that he had smuggled goods from India to Sri Lanka.“During the early 1990s, I used to go India by sea and buy petrol and diesel from there to sell it in Sri Lanka,” he said. “At that time petrol was only Rs 10 a litre in India and I could sell it at a price more than 10 times higher.” The bombing of Mannar bridge by the LTTE in 1990 made the transportation of goods from elsewhere in Sri Lanka into Mannar a tough task so the people found it easier to get goods from India. Now the situation has changed and no one is interested in going to India, and also the laws are stricter. A Sri Lankan who now sails into India without a passport would no longer be allowed in as a refugee but would be sent back or kept in custody for violating immigration laws. A few years back, when the immigration laws were not strict, there was a huge outflow of Talaimannar residents to India by sea. Rev T. Navaratnam, a priest of a church at Talaimannar, confirmed that none of them travelled on passports. According to the people who live in Talaimannar, about 90 per cent of the population had been to India through the sea route and had lived in refugee camps at India. Many houses here have been locked up for years as the owners are still in refugee camps in India. Frank Vellachami, 37, who had lived 10 years in one such refugee camp, recollects that he left Talaimannar on June 27, 2006 with his family, travelling in their own fishing boat at night with two other families and reaching Dhanushkodi by 5am. There, they straightaway surrendered to police and were sent to the refugee camp. During the civil war, India was familiar with the inflow of refugees. According to UNHRC data, there are 117 refugee camps in Tamil Nadu. An interesting bit of trivia shared by the refugee returnees was that there were cricket and volleyball tournaments played between these refugee camps. When asked about the life inside the refugee camp, Periyasami Kanakarasa,40, explained that the Indian government provided adequate facilities. Camp residents were given a monthly grant about Rs. (Indian) 3,500 for a family of four along with ration of 12kg of rice per person and 5 litres of kerosene for a family. Though refugees were allowed to work outside the refugee camps, they were not allowed to own any possessions. Some had bitter experiences at the refugee camps during the tensions following the LTTE’s assassination of Rajiv Gandhi in 1991. Sunil, 49, who said he had been in India at that time said he and others had been taken to jail at Vellore. They did not face abuse but their incarceration restricted their ability to work. They were allowed to live with their families inside jail. “Only the women were allowed to go outside of the jail, for three hours every day to buy provisions,” said Mr Sunil. Mr Sunil and his family was released from jail on 1995. The government of India maintained it had been taken into custody in order to protect them from attacks by Indians outraged by the assassination of their prime minister. Nevertheless, even after two decades, some refugees who had been taken into jail like Mr Sunil and his family are still imprisoned in Vellore and Puzhal in Tamil Nadu even though, Mr Sunil says, they had proved they had no LTTE connections. When asked about such Sri Lankan refugee prisoners in India, the Ministry of Rehabilitation and Resettlement said it was aware of this fact and was in talks with New Delhi. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which is facilitating the return of Sri Lankan refugees, said it could not comment as the issue. With the recent inflow of Sri Lankan refugee returnees, the village is again back to business as many have returned from India and many are yet to come. Last week four more families have returned from India, after their 10-year stay at refugee camps. They returned as part of the UNHCR’s voluntary repatriation programme and almost 70 persons returned to

|

Talaimannar, on the north-western coast of the Mannar district, was the main jumping-off point for Sri Lankans fleeing from their homeland. It lies only 18 miles far from the Indian town of Dhanushkodi, the main destination for the refugees.

Talaimannar, on the north-western coast of the Mannar district, was the main jumping-off point for Sri Lankans fleeing from their homeland. It lies only 18 miles far from the Indian town of Dhanushkodi, the main destination for the refugees.