Those unwanted dark velvety patches

View(s):Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) is a preventable and treatable disease if early signs are heeded, says Consultant Endocrinologist Dr. Dimuthu T. Muthukuda

By Kumudini Hettiarachchi

Just a walk past and closer look at any group of adolescent girls will show up the tell-tale marks. While many of them will have pimples (acne), which everyone erroneously assumes is a purely teenage problem, there will also be hair-growth on the face where it should not be and a dark velvety patch on the neck.

These could be early signs of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS), stresses Consultant Endocrinologist Dr. Dimuthu T. Muthukuda, adding that it is a “highly prevalent” disease condition.

The good news is that it is preventable and also treatable, MediScene learns, with the sooner treatment starting, the better. Unfortunately though, according to Dr. Muthukuda, it is not identified as an ailment especially in this part of the world.

Before dealing with PCOS, she gives some background about insulin-resistance to which those living in South Asia are more vulnerable than those in other parts of the world, with such insulin-resistance being a risk factor for the later development of Type 2 diabetes. Here is where the other link arises – while insulin-resistance is a very important South Asian risk factor for future diabetes, it also goes hand-in-hand with PCOS.

Secreted by the pancreas, insulin is the hormone (chemical messenger) which helps a person’s cells to utilize glucose or sugar, found in the carbohydrates she/he eats, to produce energy. Those with insulin-resistance have trouble absorbing glucose which, in turn, leads to a build-up of sugar in the blood. Insulin also regulates the blood-glucose levels and this is why if there is insulin-resistance, there would be blood-glucose levels higher than normal bringing in a pre-diabetes condition and if not dealt with finally leading to diabetes.

Secreted by the pancreas, insulin is the hormone (chemical messenger) which helps a person’s cells to utilize glucose or sugar, found in the carbohydrates she/he eats, to produce energy. Those with insulin-resistance have trouble absorbing glucose which, in turn, leads to a build-up of sugar in the blood. Insulin also regulates the blood-glucose levels and this is why if there is insulin-resistance, there would be blood-glucose levels higher than normal bringing in a pre-diabetes condition and if not dealt with finally leading to diabetes.

Taking up PCOS next, Dr. Muthukuda, says it is ‘syndromic’ (a collection of clinical features which occur together) so there is no way that a single test can be used to diagnose it.

It has to be looked at as a whole, otherwise there could be under-diagnosis or misdiagnosis, she discloses, citing the example of a sole test such as an ultrasound scan finding cysts (tiny liquid-filled rounded structures) in the ovaries (the female egg-producing organs), which could lead to the ‘wrong labelling’ as PCOS.

Pointing out that females and males get their gender identity, physical features and behaviour from the sex hormones – oestrogen and androgens respectively — this Consultant Endocrinologist explains that in both, the other hormone is also present in minute amounts. However, in PCOS, the male hormone in that particular female becomes a “little bit” hyperactive, with a relative increase of androgens.

This results in a dramatic physical change and a hormonal imbalance in the form of:

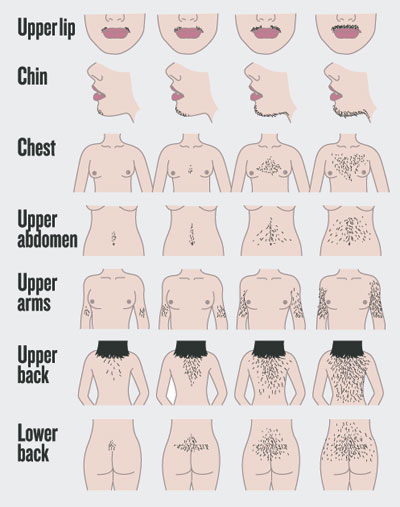

Hyperandrogenism – excess of androgens causing male hair-patterns (hirsutism) in adolescent females who suddenly find unusual hair growth over the face, chest, stomach, back of chest, upper arms and thighs.

A rash of acne

Menstrual irregularities – such as oligomenorrea (infrequent period) or amenorrhea (absence of period).

Dr. Muthukuda says that usually a female would get her monthly period roughly in and around 28 days, but those having PCOS may not have a period for months on end or an absence of the period for one or two years. “Simultaneously, she would gain weight (obesity) and develop acanthosis nigricans where a dark and velvety discolouration would mar body folds and creases such as the neck, armpits and groin.”

The spectrum could affect any female starting from menarche to middle-age, it is learnt, with the presentation of symptoms varying from age to age. PCOS may take on a more prominent cosmetic appearance in adolescence while in young married women it may be sub-fertility issues (difficulty or inability in conceiving a baby).

Depending on the age of the patient, it is important to address what their current need is, says Dr. Muthukuda, adding that going by what Endocrinologists have seen PCOS seems to be “highly prevalent” even in women who are in the reproductive age.

Box II: A disease of exclusion

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) is “a disease of exclusion”. The diagnosis of PCOS should be made after excluding any other secondary cause, MediScene understands.

A detailed case history has to be taken as well as a careful examination of the hair pattern – its distribution and severity measured against the Ferriman Gallwey (F-G) Score, an evaluation of hirsutism – says Dr. Dimuthu Muthukuda. The ‘absolute’ criterion is to exclude other conditions such as thyroid problems, hyperprolactinaemia, congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and malignant tumours secreting the male hormone.

The tests needed to ascertain PCOS include:

The tests needed to ascertain PCOS include:

An ultrasound scan (cyst-imaging) to check out whether there are cysts in the ovaries

A blood test to determine whether there is an excess of androgens (male hormone)

Once the absolute criterion has been ruled out, if the patient has two of the following three – male-pattern hair growth, menstrual irregularities and an ultrasound finding of cysts in the ovaries, then the diagnosis should be PCOS, according to Dr. Muthukuda.

Gentle advice flows forth from this Endocrinologist in the case of women in the menopausal age. Then it becomes a ‘differential’ diagnosis, for symptoms such as male-pattern hair growth may have a more sinister cause or be a feature of a bigger problem such as a male-hormone producing tumour or resulting from an ovarian pathology. Those need to be investigated thoroughly, she adds.

| Treatment to fit the need Targeting treatment to meet the need, is the best way to handle patients with PCOS, says Dr. Dimuthu Muthukuda, while underscoring that catching it early would be the best. In adolescents, the cosmetic appearance would have to be dealt with even as the treatment is on. The patient may be advised to seek such measures as physical hair-removal, of course, from a reputed salon, so that the patient does not feel insecure due to her appearance or be wracked by image-loss. In women in the reproductive age, with ovarian dysfunction causing sub-fertility issue due to insulin-resistance, that would have to be addressed quickly.“Treatment is long drawn out, a minimum of at least six months and patient-compliance an essential factor. But it works,” says Dr. Muthukuda, pointing out that as the treatment takes effect, the unwanted hair growth will stop and the acne will regress. Weight loss will allow the menstrual cycle to right itself spontaneously.Giving a few pointers how PCOS may be managed, she says that if it is a young girl, her period may be induced by putting her on the pill but if in the late 30s and her ovaries are not functioning, there would be limited time if thinking of conception. Then fertility-induction techniques to induce ovulation may be the answer. Metformin, meanwhile, increases insulin-sensitivity and would help ovulation improvement and also weight loss.Urging not only parents but also principals and teachers who see adolescents, day in and day out, to guide the children in the direction of seeking help if they spot the tell-tale signs, she says that PCOS is easily preventable and also treatable.Simple lifestyle changes, such as eating a healthy and nutritious diet and exercising regularly, will lead to weight loss and prevent obesity. These are the mainstays of therapy, MediScene learns, as in other non-communicable diseases such as diabetes.Being not only a professional but also a wife and mother, Dr. Muthukuda is quick to point out that a healthy diet should be woven in to the meals of the whole family. There should be no special meals for the patient with PCOS, as it may not be practical long term. Such a diet is also good for all and should be workable within the home structure. Even when eating a healthy diet, be conscious of portion size. Adolescents should also have earmarked play-times where they engage in physical activity. What is happening currently is that they go to school, then for tuition and when they return home they either take up their books once again or sit in front of the TV or computer. There is no physical activity at all and that needs to change, she adds. | |

| A disease of exclusion Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) is “a disease of exclusion”. The diagnosis of PCOS should be made after excluding any other secondary cause, MediScene understands. A detailed case history has to be taken as well as a careful examination of the hair pattern – its distribution and severity measured against the Ferriman Gallwey (F-G) Score, an evaluation of hirsutism – says Dr. Dimuthu Muthukuda. The ‘absolute’ criterion is to exclude other conditions such as thyroid problems, hyperprolactinaemia, congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and malignant tumours secreting the male hormone.The tests needed to ascertain PCOS include: An ultrasound scan (cyst-imaging) to check out whether there are cysts in the ovaries A blood test to determine whether there is an excess of androgens (male hormone) Once the absolute criterion has been ruled out, if the patient has two of the following three – male-pattern hair growth, menstrual irregularities and an ultrasound finding of cysts in the ovaries, then the diagnosis should be PCOS, according to Dr. Muthukuda.Gentle advice flows forth from this Endocrinologist in the case of women in the menopausal age. Then it becomes a ‘differential’ diagnosis, for symptoms such as male-pattern hair growth may have a more sinister cause or be a feature of a bigger problem such as a male-hormone producing tumour or resulting from an ovarian pathology. Those need to be investigated thoroughly, she adds. |