Tracing a spice connection

Dr. Lodewijk Wagenaar in Colombo. Pic by Indika Handuwala

One could say that Dutch historian Dr. Lodewijk Wagenaar’s passion to discover more about the lands in Asia was ignited in his grandmother’s kitchen. The smell emanating from the waffles and cookies she baked and their deliciousness fuelled his curiosity to find out more about the lands where the spices used extensively by the Dutch in their cooking came from.

It took him many more years to reach the shores of Sri Lanka, the island nation his forefathers had held sway over for over 150 years when Dutch power was at its zenith in the region and the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC), better known as the Dutch East India Company controlled all the major trading posts across Asia with Ceylon among its prized possessions.

Dr. Wagenaar’s first visit to the country in 1980 was nowhere as eventful as the arrival of fellow countryman Joris Van Spilbergen through whom the Dutch first made contact with Ceylon in 1602, but his fascination with the country is likely the same. Over the past two and half decades, Dr. Wagenaar, who is a lecturer at the Department of History at the University of Amsterdam, has embarked on a mission to document various aspects of the Dutch period in Ceylon.

In his newly published book “Cinnamon & Elephants”- Sri Lanka and the Netherlands from 1600, Dr. Wagenaar has used archival material at the Rijksmuseum –the National Museum of the Netherlands – to recreate the Dutch period in Ceylon and piece together some fascinating details of what life was like for both the colonizers as well as the indigenous population during the period.

He has framed the Dutch period in Sri Lanka into three categories- Arrival (1602), Conquest (1638-1658) and Loss (1796) – the latter being the year the British arrived and took control of the country’s maritime provinces.

For Dr. Wagenaar, teaching about “Colonial History” has become rather complicated with different ideas of how best to interpret the era when European traders turned aggressors in order to secure their share of the bounty from newly discovered lands in Asia. What he now teaches is termed “An encounter between the east and west”. “Out of a kind of political correctness, this is the term which is now used to describe the Dutch occupation,” Dr.Wagenaar says, adding that the choice of words is not exactly to his liking and puts it bluntly in his book, “The Dutch conquest of Ceylon was about one thing: money.”

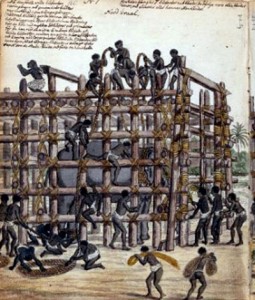

Restraining a wild elephant in corral (1785)

Whichever way one chooses to look back at the Dutch period in Ceylon, there is no doubt that the study of the period continues to generate interest among historians in both the Netherlands and in Sri Lanka and new details continue to emerge about the era. It was mainly in the search for cinnamon and other spices that the Dutch sailed across the seas, eager to take control of trade in the area as it was becoming increasingly difficult to depend on other traders to get them adequate supplies across to Holland with several wars waging in the European continent. Upon landing in Galle, they were confronted by the Portuguese who were occupying these areas and it was after a lengthy war between 1638-1658 that the Dutch finally took control of the cinnamon plantations in the country’s coastal areas,” he says.

The Dutch had moved quickly to make contact with the King of Kandy and the King in turn, weary with the Portuguese occupiers, invited the VOC to help him expel them. Once the Portuguese were ousted, the Dutch were in no mood to leave and turned the tables on Raja Sinha II who had sought the help of the VOC telling him,” We are here to help you Sire but we will not leave until you reimburse the costs we incurred by waging war for you.” They set the amount at millions of guilders which the King was in a position to pay. From then on for nearly a century and a half, the Company, having taken control of almost the entire coastal line of the country, consolidated itself on the island and while the initial aim was only to export cinnamon , the “VOC moved swiftly to open up the entire territory for financial gain.”

Dr.Wagenaar explains that what followed was an uneasy truce during most of this period between successive rulers of Kandy and the VOC with the Dutch using their military might to coerce the local rulers into several agreements which gave them a free hand to trade and exploit the resources in the coastal regions while they also used soft diplomacy to appease the kings with annual emissaries sent to the Kandy Kingdom bearing gifts. “The two sides agreed to disagree and annually the Dutch sent gifts worth 25,000 guilders brought from foreign lands including porcelain from China, furniture from Japan and Persian horses which the king particularly liked,” Dr.Wagenaar said.

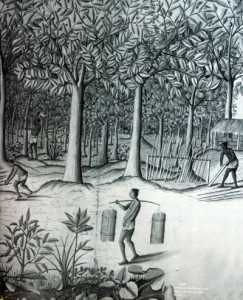

For the Dutch, as for all European colonisers, cinnamon was the major attraction, the best quality of which was on the island and fetched high prices. First the Dutch increased the cultivation of cinnamon in the coastal areas and then ventured about a kilometre interior from the coastline and here too they experimented with growing the spice and found it to be a major success. “The first major experimental plantation was at Maradana, where the present railway station is located. After that the plantations were expanded to other areas including the area which continues to be called Cinnamon Gardens in Colombo,” he explained. With almost the entire coastal areas under their control, the Dutch used all kinds of ways to coerce the King to allow them to expand the plantations into areas where the King’s writ ran and also to ensure that the local population worked as labourers without whom the cinnamon trade would have collapsed. “At one point, the King was told that in exchange for salt, the King would have to co-operate with the Dutch and not hinder the cinnamon trade. The king who had by that time little or no access to the coastal areas had to accede to the Dutch demands as salt was essential for the people,” Dr.Wagenaar explained.

Besides cinnamon, the Dutch also exported elephants which though not as lucrative as cinnamon fetched them a handsome amount.

“Five elephants, presented to the Company by the King as a gift or in return of expenses, arrived (in Matara), large and fine, will fetch a high price,” says a letter sent to the VOC directors in the Netherlands on December 18, 1639.

Dr.Wagenaar said the elephants were procured mainly from Matara and Galle and were marched along the coast to the North where they were auctioned to Muslim merchants from South India. From here they were taken across the Palk Straits on dhows to be sold to temples, for work as well to be presented to the Maharajas in India.

Unlike the cinnamon trade, the trading of elephants was fraught with dangers as well as great risks as capturing them and transporting the animals across hundreds of miles was an arduous exercise. A series of drawings by a famous Dutch artist Jan Brandes (1743-108) which gives a rare glimpse into how the animals were captured and then tamed before being taken for the auction, is included in the book by Dr. Wagenaar.

The drawing shows the animals being driven by men carrying flaming torches, shouting and beating drums into large corrals that were erected using wood. Once the animals were trapped they were restrained using rope and mahouts were employed to tame them. Then they were led out of the corral one by one. At least 20-30 elephants were exported each year with tuskers fetching higher prices, he said.

Despite the general mistrust between the local ruler and the foreign occupiers, there were occasions when the two sides worked together to their mutual advantage. One such occassion was when King Vimala Dharma Suriya (1687-1707) requested the VOC ships to take Kandyan emissaries to Arakan (now Rakhine in Myanmar) for the delegates to verify if there existed the pure form of Buddhism in that land and if so to request a delegation from there to return to Ceylon to be ordained here. The mission was a success and the VOC ship returned with 33 monks and a upasampadha (higher ordination) was held for them.

“Cinnamon & Elephants is a reflection on the shared history of the people of Sri Lanka and the Netherlands with Dr.Wagenaar giving his interpretation using visual representations such as paintings, maps and artifacts as well as written sources drawn mainly from the archives of the Rijksmuseum, where he once served as its curator. But he knows that such interpretations are relative and in 20 years’ time other observers may draw their own conclusions by looking at the same objects.

Transporting peeled cinnamon (1700)