The Dutch connection woven into our society

View(s):

Pic courtesy Threeblindmen

This attractive and sumptuously illustrated publication offers an evocative treatment of one of Sri Lanka’s most tumultuous historical periods. The book examines the events from April 1602 when the Dutch made their initial incursion into Sri Lanka’s territorial waters in the command of a fleet under Joris van Spilbergen.

Although the country’s Maritime Provinces were under colonial subjugation for a little over four centuries from 1505-1815 their presence had a lasting impact on every facet of the nation from architecture to cuisine. Dutch rule in Sri Lanka was singularly exceptional in that the civil, military, judicial and economic activities of the territory were carried out by a trading institution, the Dutch East India Company, known world over as theV.O.C.

Lodewijk Wagenaar, in his role as a curator at the Amsterdam Museum, first visited Sri Lanka in 1980 to establish the Dutch Period Museum in Colombo, which opened on 2nd Cross Street, Pettah, in July, 1982. Over four decades Wagenaar was involved in numerous assignments related to the several aspects of Dutch legacy and other cultural activities, both in varied roles as a researcher and educator.

In this publication Wagenaar charts the East India Company’s influence over this island through multiple channels – mercantile, social and cultural. Its officials were the colonial masters, the pyramid of power being headed by a Governor and his Council based in Colombo.

Unlike their Lusitanian neighbours, the previous colonial ruling power of our coastal territories, the role of the Dutch Reformed Church was not pronounced. Trading and barter helped spread Dutch influence throughout Sri Lanka. Thus the company’s trade mark VOC impacted every facet of their presence and this is the reason why present day collectors of antiques value and treasure every object which has the Company’s seal engraved, carved, printed or stamped on it.

Lodewijk Wagenaar in 216 pages with as many illustrations takes on a historical survey of the country the Dutch came to know as their home away from home. In an enlightening aside in his book he points out one of the social issues that was worrisome for the Dutch Administrators:

“The administrative elite was allowed to bring their wives or families with them, but ordinary VOC employees had to make their journey to Asia alone, and it has long been customary for sailors, artisans and seamen at VOC trading post to have relationship with local women. – The very earliest sources after the capture of Galle in 1640 mention such relationship. One consequence of this phenomenon was the establishment of the orphanage in 1644.”

Further on he adds- “Although concubinage was officially forbidden, it was very common for VOC employees to live unwed with women who were either freed slaves or whose parents had been slaves.” [Page 127-8]

The consequence of this was that 60% of the employees of the Company up to the middle level in Galle were of mixed ancestory and this number was slightly less in Colombo.

As rulers and settlers the Company officers had made this country their home and were reluctant to return to Netherlands or accept a post in another of their colonies.When the Dutch VOC finally conceded their territories in Sri Lanka to the British in 1796, only a small section of the officers actually returned home to Holland. Many of the senior officers took on whatever government post offered to them by the incoming British administration, and soon became a part of the social fabric.

In several ways this book highlights the social, racial and other aspects, which over the years has been woven into the customs of Sri Lankan society.

The author highlights another fascinating feature of a legacy that has now been interwoven into our own society. It is now a feature of our own cuisine and culinary practice that was originally a part of Dutch legacy, but which still lingers on in our country.

Describing kitchen utensils, which were uniquely Dutch he says;

“But there were also characteristic items in the domestic environment that showed who belonged to the privileged “European” community. Burghers used these items to distinguish themselves from Muslim or Sinhalese citizenry. Typical examples include biscuit moulds, waffle irons for making stroopwafels (Dutch syrup waffles), and pans for making poffertjes [miniature pancakes.) The most typically Dutch of all was the broder a pudding also known in Netherlands as jan-in-de-zak (jan in the bag) which is boiled in a bag. In Ceylon however, it was usually cooked in a heavy pot called a broederpan.

The characteristic Dutch broederpan often crops up in inventories and auction records. In 1791 for example the Colombo burgher Pieter de Almeida (originally a Portuguese name of course) apparently owned one”. [P145]

He also points out that in a list of auction goods belonging to Henderik Willem August Keneuman who originally arrived from the German city of Oldenburg in 1755, he had by then adapted himself to the Dutch-Sri Lankan environment, as illustrative from the items listed in his kitchen which included a poffertjespan, a broederpan and also a pannenkoekspan (pancake pan).

The Dutch like the British who came after them could never adapt their taste buds to the native culinary habits even though both colonial rulers lingered on in Sri Lanka for a total of over three centuries.

Although over the years, Cinnamon and other spices have become an integral part of European cuisine, unfortunately in the text the author has confined himself only to a mere 21 pages [pp. 147-168] for this fascinating subject. In the balance of the work, he largely focuses on other interesting facets of the manner in which the Dutch adapted their lifestyle to suit their own in a tropical country.

On the relationship between the Kings of Kandy and the Dutch, the author has interesting observations to make. He highlights another aspect that differentiates the two nations. In the perception of diplomatic courtesies and etiquette, they were poles apart. This after all was an integral and essential element of statecraft in the 16-19th century when ambassadors were used to receiving or dealing with, Royalty, aristocracy and other high officials, especially in the Orient, where status and caste play a vital role.

These rituals had to be strictly followed, after all this could make or break the cordial relationships between the two countries.

The Kandyan Royalty demanded that all officials, envoys of embassies were to kneel before the King in his chamber or during public audience.

Although this was the practice, which was strictly adhered to for a century after, at their first Dutch envoy’s visit to Kandy in 1656, the Dutch Governor found this an irksome practice and wished to do away with it and had a clause included to this effect in the latest treaty that was signed the year after the invasion of the Kandyan capital in 1765. Taking the upper hand, and flexing their muscle, the Dutch High Command, tired of being humiliated let it be known that whatever the consequences they would not kowtow before the King!

The author points out that try as they might the Dutch lost out on this delicate but embarrassing issue but in the end the ambassadors were coerced into kneeling before the King.

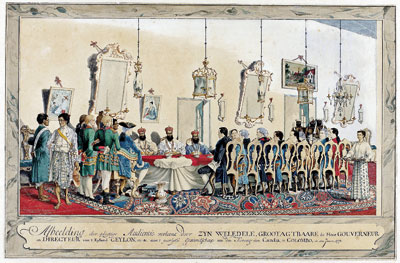

Rajadi Raja Sinha [1782-1798] made it quite plain that there was no likelihood of continuing further deliberations, if they could not afford to pay such respect to the almighty King of the Kingdom of Kandy. The Dutch Ambassador Frederik Jacob Billing’s protestations were ignored and he was forced to kneel for hours during his visit during the audience that took place on May 30, 1783. There was an element of humour and pathos in his plea that “he could give this honour to no one but the Creator of the heavens and earth”. The artist Jan Brandes has vividly captured the scene of this event in 1783. There are many such incredulous and intriguing facts that Wagenaar highlights in the text that makes this book a fine read for any one interested in history.

In the last two chapters in the book, Wagenaar has appended two additional sections on vintage photographs of Sri Lanka in the 19th century, – titled ‘Photographers in Ceylon 1870-1930’ and ‘Intermezzo9-Colombo in Photographs’ .

Although there are some fascinating images, the exact significance of this chapter to Dutch rule in the history of Sri Lanka is not clear to the reader. Photography was introduced in the early 1840s and it was purely a 19th century British phenomenon- and was largely dominated by them.

For those interested in our colonial past, however uncomfortable it may seem to endure, the book deserves to be widely publicised

| Book facts: Cinnamon & Elephants- Sri Lanka and the Netherlands from 1600- by Lodewijk Wagenaar [RijksMuseum]. 2016.Vanity Publishers]. Reviewed by Ismeth Rahim |