SL’s new development paradigm: Factory jobs vs desk jobs in 2020

According to the economic development plans declared by the government, it is clear that industrialisation has been identified as a catalyst to propel Sri Lanka’s economic development.

Industrialisation would be an appropriate development strategy for Sri Lanka due to its strategic location in the Indian Ocean and high investment in public infrastructure. It would attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and new technology to the country while increasing government tax revenue, export earnings, etc…

Moreover, one of the imperative benefits of industrialisation would be the creation of new employment opportunities. Specifically more job openings for blue collar jobs such as plant and machine operators, technicians, assembly and packing line labourers and other labour related jobs. The government intends to achieve its ambitious plan of creating one million jobs primarily by developing Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in different parts of the country. In order to execute industrialisation plans, the government is currently assessing an economic partnership with India and bilateral trade agreements with China and Singapore. A similar approach was taken by the Premadasa government in encouraging the establishment of small scale garment factories in rural areas. This was an effective solution to curtail unemployment which prevailed during that era.

Due to changes in aspirations of the Sri Lankan labour force, could the government generate jobs for local youth via industrialisation? The purpose of this article is to question the suitability of industrialisation as a strategy to create employment opportunities for the current Sri Lankan labour force. Even though this is a premature question, it is important to assess the impact and likelihood of possible outcomes to take preventive actions.

If the government is able to attract FDI and set up SEZs, it will certainly create new job opportunities, particularly unskilled and skilled blue-collar jobs. But it begs the question as to whether the present youth labour force is willing to undertake in large numbers blue-collar jobs in factories.

Facets of the Sri Lankan labour

market

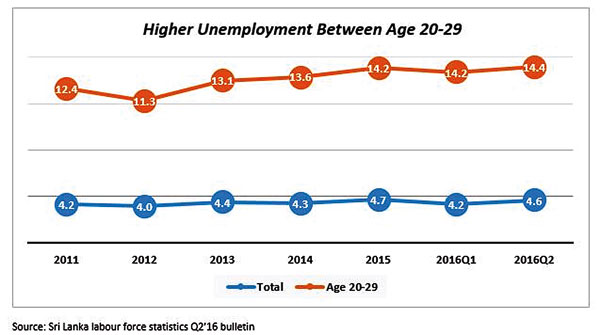

The unemployment rate is one of the key macroeconomic factors to measure economic performance in any country. Sri Lanka is experiencing a downward trend in unemployment rate over the years and currently remains at 4.6 per cent as per Sri Lankan labour force statistics (Q2’16 bulletin). Liberalization of trade policies, commencement of industrial zones, and provision of free education up to state universities, gradual increase in female workforce and surge in foreign employment opportunities for both blue- and white-collar jobs could be identified as some of the significant contributors to reduce unemployment rate over the decades.

However, the unemployment rate among youth is still at a higher level despite the decline in the overall unemployment rate. This is a chronic social issue prevailing in the country, which needs to be managed by the government in participation with the private sector.

Shift from blue-collar to white-collar

One would define white-collar jobs as highly professional careers whereas another would refer it to any clerical and administrative functions. In this article, the writer uses the term white-collar jobs to describe any job other than blue-collar jobs at factories.

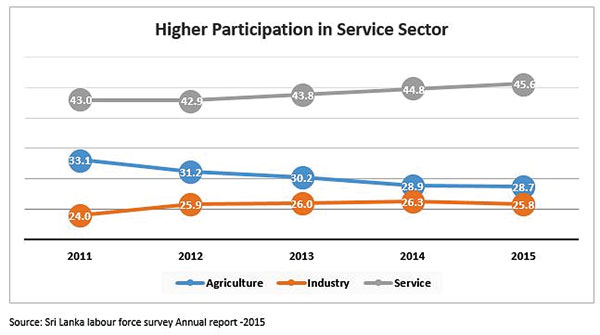

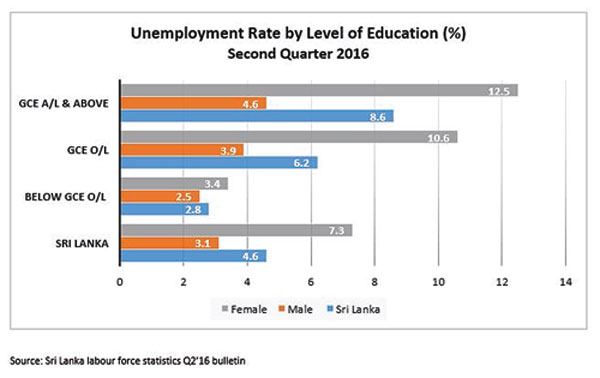

Local labour participation has been shifting from the agriculture sector to industrial and service sector over several years. The service sector provides the majority of employment opportunities and growing at a steady rate. Looking at the Sri Lankan labour force, it is evident that current job seekers are in pursuit of white (desk jobs) and pink-collar (work associated with women) jobs over blue collar jobs. Further analysis of unemployment by education level portrays that unemployment is highest among who possess education qualification A/L and above. This could be one of the reasons to generate a higher supply for white-collar jobs.

The above mentioned trend is not an unexpected outcome. This trend is a result of several socio economic factors prevailing over a period of time. Higher earning potential, other benefits, job security, career growth, healthy and safe working environment and social recognition are some of the popular merits of white- collar jobs compared to blue-collar jobs. In today’s rapid digitalisation era, Millennials and Generation Z would prefer to sit in front of a computer in an office environment, instead of working in a steaming, noisy factory.

There is an excess supply for white-collar positions such as clerks and clerical support services, shop assistants, administration/sales assistants, customer service, etc. Even though, Sri Lankan job seekers aspire to move in to the service sector, there is an unfulfilled demand in the service sector due to lack of essential skills such as English and IT. The current education system has been battling to improve soft skills of students which are vital to fulfill future employment opportunities, which is another key topic to be discussed but beyond the scope of this article.

When the government formulates strategies to combat youth unemployment by setting up SEZs, it might not be able to deliver expected results due to above trends in local labour markets.

Shortage of local skilled labour

At present the Sri Lankan industrial sector is struggling to source skilled labour predominantly due to the migration of skilled workers overseas for higher wages and growth prospects. Firstly, after obtaining the required vocational qualification/certification from Sri Lanka, blue-collar workers migrate overseas for greener pastures similar to white-collar migrants. Foreign workers’ remittances play a pivotal role as the largest foreign exchange earner in the country. Secondly, as explained, the gradual shift towards office jobs would create a labour shortage. On the labour demand side, employers are also unable to provide higher wages to attract blue-collar workers due to cost pressures.

At present, the foreign employment sector mainly consists of unskilled workers and housemaids but there is plenty of demand for skilled labour which is yet to be capitalized by Sri Lanka. The Government has recognized this opportunity and certain programmes have been already initiated to enhance skilled labour migration. Nevertheless, higher migration of labour will create further pressure on the availability local labour.

The shortage of skilled labour will be further aggravated when the proposed factories are built in Sri Lanka. There will be a higher demand for blue-collar jobs in newly built factories. This vacuum in the local blue-collar job market will open windows to low cost immigrant labour from countries such as India and China. This aspect is visible when observing some of the ongoing construction projects in Sri Lanka. Similarly in future, such immigrant workers will be employed by foreign investors to operate their plants flawlessly at a lower cost. Evidently, they would require government clearance to deploy foreign workers in Sri Lanka. At some point due to the shortage of local workers, the government might not be able to decline such a request at the outset to facilitate smoother operations of SEZs.

In the midst of these possible scenarios, local youth unemployment rate will remain an unaddressed issue due to the mismatch between industrialized job demand and local labour market supply.

Conclusion

The government’s economic development plans for industrialization has over-shadowed the growth prospects in the service sector. Being the largest contributor to the national GDP, there is further potential to make the service sector more vibrant and export oriented. Policy makers should attempt to link the dots between higher youth unemployment with the potential growth of the service sector. A well-crafted, export-oriented service sector will be one of the key tools to resolve youth unemployment and fuel export sector growth.

Sri Lanka cannot be a factory for the world like China or India due to limitations in its inherent structures. But Sri Lanka could position itself as a reliable service partner by leveraging on strategic service sectors such as tourism, information and communication technology, business process outsourcing, financial services, health care services, construction services, higher education services, etc. However, we rarely notice that policy makers formulate and implement nationwide strategic plans to create job opportunities in the service segment in partnership with local and foreign private sector.

(The writer is a member of the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (UK) and member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Sri Lanka and holds B.Sc. Accounting (special) degree awarded by University of Sri Jayewardenepura. He can be reached via manoshstar@gmail.com)