Arts

Words powered by pictures

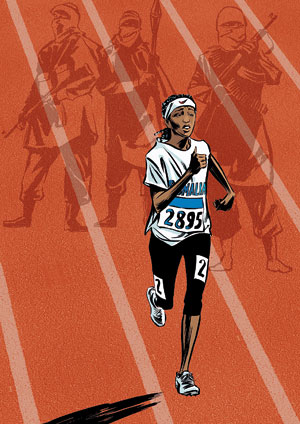

Kleist’s most recent work: Somali runner Samia Yusuf Omar who died fleeing her country

When the news broke that Fidel Castro had passed away, Reinhard Kleist was a little surprised to find himself in demand. It turned out that journalists remembered Kleist’s graphic novel ‘Castro’, which the German illustrator had produced with writer Volker Skierka in 2011.

In the book, Kleist’s narrator was a journalist who initially subscribed to the virtuous position that reporters must remain neutral, but over the course of the novel found himself developing a conflicted relationship with the young, charismatic firebrand who was Castro. Kleist dedicated whole pages to emotionally expressive portraits of Fidel, capturing him in heated debates with a president, or inhaling a signature Cuban cigar.

“Now that he is gone, people seem to be really interested in reading about him again,” Kleist who will be in Sri Lanka for the Fairway Galle Literary Festival (FGLF) from January 11-15 told the Sunday Times, adding that looking back he felt he wrote a book that was both critical and sympathetic of the man. Kleist made a determined effort to break out of a western view point, in particular paying attention to Cuban politics in relation to the countries around it. “It definitely had to do with the time I spent in Cuba,” says the artist, who was there in 2008 and learned Spanish so he could speak with locals. He found a populace that was quite deeply divided on the issue of Castro’s leadership. In the end, Kleist made sure his character made no definitive judgments.

“I find it not very interesting to tell the reader what to think,” says Kleist. “I wanted people to have their own conclusions.”

Over a series of remarkable graphic novels, Kleist has become a notable biographer. He was already well into his career when his tribute to Johnny Cash – I See A Darkness was published in 2006.The book traced Cash’s eventful life from his early sessions with Elvis Presley (1956), through the concert in Folsom Prison (1968), his spectacular comeback in the 1990s, and the final years before his death on September 12, 2003.

Critically acclaimed, it was translated into several languages and awarded the Peng Munich Comics Prize, as well as the Frankfurt Book Fair Sondermann prize. In 2008, it also received the most prestigious German comics prize, the Max und Moritz.

In 2006, Kleist’s biography on Elvis Presley was also released, and in 2011 his book “Der Boxer” (The Boxer) told the story of Jewish Boxer Harry Haft. An Olympic Dream, the latest of his 18 novels,about the Somali runner Samia Yusuf Omar was published in 2015.

Kleist’s work is compelling, not just for the kinetic energy of his illustrations but also for his ability to portray characters with nuance, in a way that does not shudder away from moral complexity. Nowhere is this truer perhaps then in his prize-winning book on Harry Haft, a man who was sent to the concentration camps and survived by being willing to fight other detainees for the entertainment of his Nazi captors. With men from the SS betting on his victories, Haft was soon dubbed the “The Jewish beast” by his captors.

Kleist based his book on a biography written by Haft’s son, who traced his father’s journey through Auschwitz, and then to days of the Soviet Army advance in 1945, during which Haft made a daring escape. Eventually he made his way to America, where he struggled to find his place in a strange new society, even attempting to become a professional boxer in his new life, remaining undefeated until he faced heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano in 1949.

For the reader, Haft is not always a sympathetic character. In one particularly searing section, the man brutally takes the lives of innocents in an attempt to protect himself. “For me the challenge was to understand what he is going through, to understand his perspective, and that is something that is also a challenge for the reader,” says Kleist. He succeeded in part by creating a tender love story that anchored Haft throughout the book.

Reinhard Kleist: Standing up for what he believes in

In depicting the holocaust from the experiences of someone who actually experienced its horrors first hand, Kleist had to think like a film director. There are sections where the character works in the crematorium and another that hints of cannibalism among desperate captives. “My idea was to show it by not showing it,”says Kleist. “It was as I was putting the camera far away or making it blurry.”

In fact, this cinematic approach guides Kleist in creating a new work. “It is like watching a movie inside my head, and then I translate what I see into a sequence of pictures,” he says, admitting that when he started out he didn’t think himself a very good artist. While that has changed, his recent years have been dedicated to exploring different techniques of expression, and with an interest in experiments along the lines of the work done by artists like Dave McKean and Ken Williams.

The stories he chooses to illustrate, have usually come to him almost by accident. The same was true of his latest novel, a heartbreaking account of the life and death of Somali runner Samia Yusuf Omar. Omar, a 21-year-old runner from Somalia, died while undertaking the dangerous crossing from the Mediterranean Sea into Europe. Kleist follows her through a long and difficult journey, reconstructing it through conversations with her surviving family, other refugees who made the crossing and through Samia’s own words, left behind in things like her Facebook posts. The young runner risked everything for her dream of competing in the 2012 London Olympic Games, fleeing a country where even her running was considered an unsuitable activity for a girl.

“The most challenging part of it was how I, a 44-year old white European man, could put myself in the head of a young black girl from Somalia,” says Kleist. Sometimes he found words just defeated him, and in those places he stuck simply to creating evocative, beautifully shaded images of Samia’s loneliness and fear as she faced down increasingly desperate circumstances.

Kleist’s own parents were refugees, and his research for Samia’s story showed him how dire the refugee crisis really is. “To be honest, I am very anxious about what will happen in Germany and France in 2017,” he says. “I fear the worst, the tension is rising and people are more divided,” he says, speaking of demonstrations that increasingly take an ugly turn.

In these times, he believes artists have their own duty. He points to the moment where the cast of the musical Hamilton addressed Mike Pence, Donald Trump’s future Vice President, sharing their fear that the diverse America they represented would not be protected by his administration. “They were very calm and well-mannered, and I found that very brave,” he says. “At some point, we can’t just sit back any longer. We are going to have to say something and stand up for what we believe.”

Avenida Simon Bolivar: From Kleist’s book ‘Havana’