News

Passive euthanasia exists as good medical practice

Dr. Gihan Abeywardena

The focus was turned to euthanasia, assisted-suicide or mercy killing, as doctors took to the debating floor to look at an issue the country has put on the back-burner.

Organised by the ‘Mid-country Psychiatrists’ at the Tourmaline Hotel in Kandy, the friendly verbal sparring event whether Sri Lanka should legalise euthanasia or not, was preceded by whether abortion should be made legal on December 28.

Once again the jury remains out, with no verdict forthcoming. However, many in the packed audience were of the view that at least the doctors were taking the lead in discussing both euthanasia and abortion and hopefully the politicians and the people would follow suit. The livewire in organising the event was Kurunegala Hospital’s Consultant Psychiatrist Dr. Gihan Abeywardena.

With Prof. Raveen Hanwella, Professor in Psychiatry at the Colombo Medical Faculty, moderating the afternoon session on ‘Sri Lanka should legalise euthanasia’, the floor was occupied by the pro-euthanasia (proposing) team led by Consultant Psychiatrist Dr. Priyani Ratnayake from Canberra, Australia, and comprising Consultant Psychiatrist Dr. Harischandra Gambheera from Colombo and Consultant Anaesthetist Dr. Gihan Piyasiri attached to the Nuwara Eliya District General Hospital.

The anti-euthanasia (opposing) team was led by Consultant Psychiatrist Dr. Ranil Abeyasinghe from Kandy and comprised Consultant Psychiatrist/Senior Lecturer in Psychiatry, University of Peradeniya, Dr. Pabasari Ginige and Head of the Department of Philosophy and Psychology, University of Peradeniya, Dr. Danesh Karunanayake.

Pointing out that “easy death” though a complex and contentious issue, is very close to her heart, Dr. Priyani Ratnayake said that as it is a process that intends to reduce intractable pain, it should be legalized.

She went onto describe what “passive” and “active” euthanasia is. Withdrawing or withholding medical treatment with the knowledge that death will follow is ‘passive’, while ‘active’ is offering a lethal agent or administration of such an agent to a terminally-ill person. Passive also includes ‘involuntary’ and ‘voluntary’ under which a decision could be taken that there is no point in continuing treatment or there is an express wish by the patient not to continue treatment.

“Passive euthanasia exists in Sri Lanka and we call it ‘good medical practice’ where we decide that there is no point in resuscitating a person or pull off life support,” said Dr. Rodrigo.

She also dealt with ‘advance directives’ (living wills) which can be resorted to if euthanasia is legalised. Then a person, when he/she has well-functioning mental faculties can make a decision not to be resuscitated or not to be put on life support later. (Advance directives are legal documents allowing people to spell out decisions about end-of-life care, ahead of time.)

Dr. Rodrigo argued that dysthanasia or bad death was the common fault of modern medicine which has helped to extend biological life, whatever the quality of that life is. “Be it good or poor we prolong life. We are supposed to cure patients but should we also not alleviate and relieve suffering,” she asked, adding that the patients should have the right to refuse treatment. This is why euthanasia should be legalised and legislation put in place to practise it.

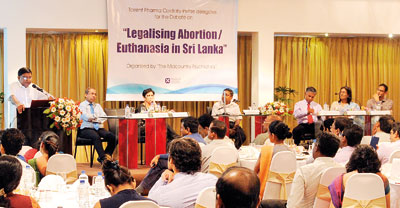

Moderator Prof. Raveen Hanwella is flanked (on the right) by Anti-euthanasia Team Leader Dr. Ranil Abeyasinghe and Dr. Pabasari Ginige and Dr. Danesh Karunanayake; and (on the left) the Pro-euthanasia Team Leader Dr. Priyani Ratnayake and Dr. Gihan Piyasiri, while Dr. Harischandra Gambheera puts forth his arguments. Pix by Amila Gamage

It is with a long quotation from William Shakespeare’s Hamlet that Dr. Harischandra Gambheera launched his arguments, pointing out that almost all religions believe in the sanctity of life and condemn suicide or assisted-suicide.

“Religions where there is a creator believe that suicide amounts to murder as life does not belong to them. They are only stewards of life. However, in Buddhism and a sector of Hinduism your karma is responsible for your life and therefore suicide is not considered murder,” he said.

Dr. Gambheera pointed out that all humans do not a have similar inherent value in the sanctity of life and that even all ages of life, between birth and death, are not equal.

Going on to ‘natural selection’, he said that the basis of evolution is this, but humankind has stopped it and taken over that task by aborting malformed foetuses. “We control births through contraceptives, abortions (medically or surgically) and abstinence. We control unnecessary births but not necessary deaths. Why not allow assisted suicide, the right of the invalid?”

According to Dr. Gambheera euthanasia is perhaps the most urgent, multi-dimensional and challenging subject of medical ethics. It has many ramifications. Is the performance of euthanasia a morally acceptable practice? If so, how should it be done? Euthanasia occurs in many countries and where it is illegal, it is resorted to secretly. Giving a fatal drug is an ethical problem but the most important ethical phenomenon is to respect autonomy. Consent should be after understanding what is to be done and evaluating the risk and benefit and alternative acts.

Arguing that sometimes it is “not euthanasia, but euthanasia”, he questioned as to what we do to our terminally-ill relatives. Do we take them for immediate medical treatment or withhold food, fluid and medicine? Is this not passive euthanasia?

Dr. Gambheera added that assisted-suicide should only be when there is a last will giving consent and abuse should be minimised through clear guidelines, high professionalism and after seeking the opinion of a panel of professionals and relatives.

Dr. Gihan Piyasiri, meanwhile, reiterated that legalising euthanasia will not make a country go down the slippery slope.

Euthanasia is not the right to kill, because we are all going to die some day but the right to end life if one has to live with quadriplegia or motor neuron disease. You have the choice and the autonomy to end the suffering. Euthanasia is an option, where the patient can choose to end his/her suffering.

| Euthanasia plea may be due to treatable depression Condemning euthanasia, Dr. Ranil Abeyasinghe was quick to point out that in this painless killing two doctors have to examine the patient and the patient must make a request. What moral or ethical rights have two doctors to let a patient live or die. Picking up several cases abroad, he said that there has been controversy over a woman who went blind and wanted to be euthanised. It was not because she was blind that she wanted to die but because she was obsessive and could not see dirt. He stressed that in many cases of euthanasia, people want to die because they felt that they were a burden to family; there was hopelessness and loss of dignity. This sounds like depression which can be treated but they were allowed to die. “What they need is not euthanasia, but a psychiatrist.” Dr. Abeyasinghe said that a liberal attitude to euthanasia is not acceptable as it will lead towards a slippery slope. This is doubly so when we have tools to keep people alive and also kill. Then where are the barriers and what if those barriers break down. He cited the case of Harold Shipman who killed old and young people and went undetected until he murdered more than 200 patients. Here the barriers were broken down and doctors got the power to kill. Do we want to go there? Do you want to give power over life and death to doctors? It is both a moral and ethical principle. With the adage “do unto others, what you wish to be done unto you”, he was adamant that doctors should not cause death but control suffering and preserve life. Euthanasia is a major ethical and moral dilemma and should not be taken lightly, as it can destroy the ethical and moral fibre. Countering the Hamlet quotations, Dr. Pabasiri Ginige said that it was not Hamlet speaking but it was depression that was speaking. The Hippocratic Oath which doctors swear-by is very specific that they should first do no harm. This is a prohibition against killing patients. For a doctor, human life should command respect. Doctors are meant to heal and medical studies clearly indicate this, not to kill patients. The overriding mandate of medicine is humanism. Making euthanasia legal will send us down the slippery slope – first mentally-sound adults will be euthanized but after that euthanasia will target the disabled, infants etc. Will we prescribe the E-pill (euthanasia-pill) to love sick teenagers who hit the depths of depression, but bounce back soon after, she asked. “Would we be putting granny out of her misery or ridding ourselves of misery by resorting to euthanasia? We are here to alleviate suffering,” she stressed, citing the example of her elderly father who was very ill recently and also acutely confused. “We did not practice euthanasia but helped him recover so that he could play his much-loved tabla again.” Dr. Danesh Karunanayake dwelt on individualism versus collectivism; power of distance; the three pillars of democracy (Executive, Legislature and Judiciary); corruption; population explosion; social groups at risk of abuse, religious concerns and living wills. Picking on the ‘I’ and the ‘We’, he said that in individualist societies people are supposed to look after themselves and their direct family only, but in collectivist societies, Sri Lanka is considered to be one, people belong ‘in groups’ and as such take care of each other in exchange of loyalty. “It must be recognised that assisted suicide and euthanasia will be practised through the prism of social inequality and prejudice that characterises the delivery of services. Those who will be most vulnerable to abuse, error or indifference are the poor, minorities, and those who are least educated and least empowered. This risk does not reflect a judgment that physicians are more prejudiced or influenced by race and class than the rest of society – only that they are not exempt from the prejudices manifest in other areas of our collective life. Ethnic, religious and class biases would all play a role,” he said. Quoting a US report, he next spoke of living wills. The report had found that most people do not have living wills; people who sign living wills have generally not thought through its instructions in a way we should want for life-and-death decisions. Drafters of living wills have failed to offer people the means to articulate their preferences accurately; living wills too often do not reach the people actually making decisions for incompetent patients; and living wills seem not to increase the accuracy with which surrogates identify patients’ preferences. |