News

Sirisena’s presidency travails amidst dilemmas of a double-headed Govt.

View(s): Two years ago today, Maithripala Sirisena contested Mahinda Rajapaksa for the Presidency. Few expected him to win. Sirisena won, defying opinion polls, political pundits and astrological predictions.

Two years ago today, Maithripala Sirisena contested Mahinda Rajapaksa for the Presidency. Few expected him to win. Sirisena won, defying opinion polls, political pundits and astrological predictions.President Maithripala Sirisena was sworn in the very next day in a chaotic public ceremony at Independence Square, only hours after the final results were announced. Immediately afterwards, Ranil Wickremesinghe was sworn in as Prime Minister. After being sworn in, Sirisena solemnly pledged that he would not run for the Presidency again, a promise he would repeat at the Dalada Maligawa later.

It later emerged that Wickremesinghe had arranged a ‘safe passage’ by helicopter for Rajapaksa to Medamulana to facilitate a smooth transition of power. Claims were made later that there was a plan to stage a ‘coup’ of sorts, to stop announcing election results, if Rajapkasa was losing the poll. These accusations were investigated initially but there was no evidence whatsoever to proceed with.

Two years and a general election later, Sirisena is still President, Wickremesinghe is still Prime Minister and the ghost of Rajapaksa continues to haunt the Presidency. Only last week, Rajapaksa said he had a plan to topple the government in 2017. He also said that he was willing to serve as Prime Minister under President Sirisena.

Two years are a long time in a five-year term as President, especially if Sirisena keeps his promise of not running for President again. It is time to reflect, take stock and assess what could be done better.

No one pretends that Maithripala Sirisena is a brilliant political strategist in the calibre of J.R. Jayewardene. Nor does he have the charisma of Mahinda Rajapaksa. Some see him as a simple villager who took the political gamble of his life, got lucky and got the top job by being at the right place at the right time — the D. B. Wijetunge of the SLFP, so to speak.

That would be unkind. Sirisena does have his virtues. He cut his teeth in politics the hard way, joining the Communist Party and then rising up the SLFP’s hierarchy from faraway Polonnaruwa where he served as a grama sevaka and a purchasing officer for a co-operative society. With such rural roots, he had the ‘common touch’.

Sirisena had served as Minister of Mahaveli Development and Minister of Health, two portfolios which had a reputation for tender scandals but he was not tainted with allegations of corruption. He kept a low profile, was not given to flamboyance and extravagance and his family, up until 2015, kept out of the limelight. In effect, he was everything that Rajapaksa was not — which is why he was chosen to run against Rajapaksa.

Sirisena’s win surprised many because it was believed that the Rajapaksa oligarchy was so strongly entrenched in the country. His margin of victory over Rajapaksa was even more surprising: A comfortable 450,000 votes, more than double the 180,000 majority Rajapaksa secured over Wickremesinghe in 2005. It was an indication of how much Rajapaksa had alienated himself from some sections of the public, particularly among the Tamil and Muslim communities.

Having won the election though, Sirisena faced his first hurdle in governing the country: he had emerged victorious only because the United National Party (UNP) had voted en masse for him. The Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), which had been his political home for nearly fifty years and of which he had been general secretary for nearly fifteen years had thrown its weight solidly behind Rajapaksa.

Sirisena had a choice. As President, he could have remained politically neutral, aligned himself with the UNP which voted him into power or tried to regain control of the SLFP. He opted for the latter. Not only did he return to the SLFP, he also took on its leadership after a tense meeting with Rajapaksa at the then Speaker Chamal Rajapaksa’s official residence near Parliament.

Critics would argue that this was not politically astute. He would carry ‘left luggage’ from the Rajapaksa regime: Politicians tainted from allegations of corruption against whom he railed during his election campaign in which he promised clean, transparent ‘good governance’. Not only would he have to accommodate them, he would have to deal with the fallout of investigating (or, worse still, not investigating) them.

The counter argument from the Sirisena camp would be that he needed the SLFP’s numbers in Parliament to muster a two-thirds majority, so he could enact the reforms he promised. The UNP, particularly Prime Minister Wickremesinghe, agreed with this line of thinking.

Matters did come to a head during the 2015 August general election campaign. The Rajapaksa camp attempted to hijack the United Peoples’ Freedom Alliance (UPFA) nomination lists and succeeded in getting most of their nominees in. Sirisena was compelled to take the unprecedented step of making an ‘address to the nation’ to inform the country that even if the UPFA won the poll, Rajapaksa would not be made Prime Minister.

The UPFA didn’t win but came a close second: 95 seats to the UNP’s 106. To ensure that he had some degree of control over the UPFA parliamentary group which had a fair percentage of loyalists, Sirisena then made another move to bolster his numbers. He purged the UPFA National List of Rajapaksa’s supporters and appointed his own.

While many would concede that this was only sensible, in doing so he also appointed through the National List seven candidates who lost at the election: Lakshman Yapa Abeywardane (Matara), S.B. Dissanayake (Nuwara Eliya), Mahinda Samarasinghe (Kalutara), Vijith Wijayamuni Soyza (Moneragala), Thilanga Sumathipala (Colombo), Angajan Ramanathan (Jaffna) and M.L.A. M. Hisbullah (Batticaloa).

Civil society activists who fought hard to bring him in to power were aghast. Ven. Maduluwave Sobhitha Thera, the driving force behind the Sirisena campaign when it was in its infancy, was distraught and condemned the move in the strongest possible terms. It was the first hint that President Sirisena was prepared to waive the rules, so he could rule the waves.

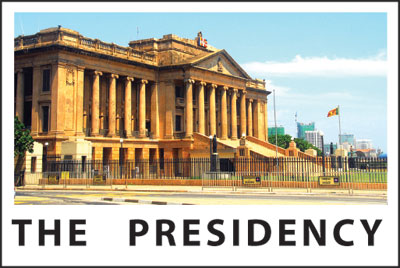

President Sirisena: Two years in a five-year term are too long a period in politics especially if he keeps his promise of not running for President again

Since then, it has been an uphill battle for President Sirisena. Rajapaksa loyalists have banded themselves together as the self-proclaimed ‘Joint-Opposition’ (JO) in Parliament and have been vocal in their criticism of the President. It is telling that of the 95 UPFA parliamentarians, a sizeable majority of 51 identify themselves with the JO. Recently, Local Government and Provincial Councils State Minister Piyankara Jayaratne quit his post, saying he only wanted to be part of a ‘wholly SLFP’ government and that he found it difficult to work with the UNP. He was afraid that the Sirisena-led SLFP would lose the upcoming local council polls that would, in turn, erode his own vote base and lead to the end of his political career.

But, President Sirisena does have achievements to showcase. He physically remained in Parliament and coaxed, cajoled and coerced the House into passing the 19th Amendment to the Constitution which restored the independent commissions and repealed the 18th Amendment. Now, Rajapaksa cannot run for President again.

He was also largely responsible for ensuring that former Central Bank Governor Arjuna Mahendran was not reappointed when attempts were made by the UNP faction of the National Unity Government led by Wickremesinghe himself to renew the Governor’s tenure. President Sirisena has also been quite insistent that the controversy over the sale of Central Bank bonds will be probed and that any wrongdoers will be dealt with properly — though that saga is yet to come to an end.

Sometime though, the President has been sending mixed messages. His public outburst against former Bribery Commissioner Dilrukshi Dias Wickramasinghe left much to be desired and led to her resignation. By all accounts, Ms. Wickremesinghe was doing an unenviable job under trying circumstances and even if the President had issues with the way she was going about her work, it could have been dealt with differently, in a more diplomatic manner. In the end, the public perception was that the President was interfering with the work of the Bribery Commission.

Indeed, the National Unity government’s battle against corruption has been one of its sore points with the general public. For a government that came to power campaigning on a platform of ridding the country of corruption and punishing those who indulged in it, it has precious little to show for it after two years. It is ironical that, despite so many politicians being paraded before the cameras at courthouses and Police headquarters, the only person who has been a casualty of the Government’s anti-corruption drive has been the Bribery Commissioner.

The President also took some early flak after appointing his younger brother, Kumarasinghe Sirisena as Chairman of Sri Lanka Telecom. The younger Sirisena is a public servant but his appointment was seen as inappropriate by many because one of Candidate Sirisena’s main themes against the Rajapaksas was nepotism. It didn’t help matters when son Daham suddenly appeared as part of the President’s delegation to the United Nations either.

Such lapses of judgment aside, President Sirisena’s job has been made difficult because he has to work with the UNP (which is not his party but the party which got him elected) and a faction of the SLFP- while the other half of his own party keeps manoeuvring to have Rajapaksa installed as the leader. The only other President to face hostility from her government was Chandrika Kumaratunga — and that United National Front government did not last long. From such a perspective, not only has the National Unity government survived, it still retains its two thirds majority and that must be a feather in President Sirisena’s cap.

However, the President often finds himself to be the ‘meat in the sandwich’ in the tug-of-war between the UNP and the SLFP groups in the government — and in the Cabinet room — which have differing policy positions on issues. The UNP was keen on the increase in the Value Added Tax, the SLFP not so. The SLFP was keen to oust former Central Bank Governor Arjuna Mahendran, the UNP not so. Now, the UNP is eager to pursue the Development (Special provisions) Bill but the SLFP abhors it — and so the list goes on.

President Sirisena must not only keeps both camps happy, he must also find a viable middle ground, so that he can make progress in matters such as taxes, key appointments and legislation, and the government can get on with the business of running the country.

If President Sirisena and Prime Minister Wickremesinghe have had differences of opinion — and they must have — they have been kept largely hidden from the public, and yet, the differences are pretty obviously open. Sirisena is to Wickremesinghe what chalk is to cheese: One, Colombo born and bred, an anglophile, an intellectual and philosophical; the other, a man of humble beginnings who worked his way to the top but richer for that experience and man with a simpler worldview.

Sirisena was only a backbench opposition parliamentarian when Wickremesinghe became Prime Minister for the first time in 1993, following President Ranasinghe Premadasa’s assassination. The President retains that respect for the Prime Minister and the feeling is mutual and therein lies the secret so far, of their cohabitation, in what could have otherwise been a difficult relationship.

But clearly, there is much more work to be done in the Sirisena Presidency. There is no denying that the National Unity Government has achieved much in dismantling the Rajapaksa Empire, ushering in a sense of freedom and law and order and restoring Sri Lanka’s image internationally. Yet, it has been equally disappointing in developing infrastructure, bettering the quality of life of Sri Lankans and ensuring that the masses are better off economically. This sense of discontent is manifested in the spate of strikes, almost on a daily basis staged by doctors, university students, private bus operators, railway workers, war veterans and now, even lottery ticket sellers.

In common parlance, the general perception is that “nothing is happening” whereas during the Rajapaksa era there was visible development and the average person was economically less hamstrung, even if millions were being paid off as kickbacks. Many voters are now saying that they prefer the latter because they believe that most politicians are corrupt anyway and the Rajapaksas had “runs on the scoreboard to show”.

At another level, the major policy changes promised by Candidate Sirisena are yet to be fulfilled. Constitutional reforms are progressing at a snail’s pace. There is no indication yet as to whether the Executive Presidency will be retained or not. It doesn’t take a genius to foresee a bigger battle between the UNP and the SLFP looming in this regard not so much as to whether to retain the Presidency in some form or another or not, but where the executive power ought to be; with the President or the Prime Minister.

There are similar issues with the system of elections. There is broad consensus that there would a hybrid system between the proportional representation (PR) system and the Westminster first-past-the-post system but the major parties have different views on which system should predominate. These are tricky issues which will determine the political fortunes of the UNP and the SLFP for decades to come, so negotiations between them are bound to be quite contentious — and President Sirisena would have to preside over them.

There are also bound to be differences of opinion about any constitutional changes that envisage the devolution of power. The UNP favours a greater degree of devolution, the SLFP, less so.

While the UNP faction of the National Unity government will be responsible for managing most aspects of the economy, seeing these constitutional reforms through will be high on President Sirisena’s agenda for that may well be what defines his presidency in the longer term. That though, will require that the President retains his hold on the two-thirds majority he now has in Parliament, which is why he has to pander to both the UNP and the recalcitrant factions of the SLFP.

Since State Minister Piyankara Jayaratne’s resignation, his subsequent statement that more SLFP ministers will follow and Rajapaksa’s forecast of ‘toppling’ the government in 2017, there has been speculation as to whether President Sirisena will be more comfortable with a majority SLFP government with a few crossovers from the UNP to ensure a parliamentary majority. The ‘elephant in the room’ question would be how he deals with Rajapaksa in that case. So then, would he prefer to remain with Wickremesinghe and the UNP, as he is now with all the aches and pains?

The President said as much to UNP MPs who sought a meeting with him just last week. The reason is simple: Whatever the differences between their political parties, the President feels more comfortable with Wickremesinghe in the Prime Minister’s chair than he will ever be with Rajapaksa as PM. Days later though, the President was reported to have met SLFP ministers and state ministers and asked them to stand up to UNP MPs who were making life difficult for them.

Torn as he is between these two positions, for Sri Lanka’s sixth Executive President, it has been a long journey, first from Yagoda in the Gampaha district to resettlement in Polonnaruwa as a child and then from Polonnaruwa to President’s House amidst all the rough and tumble of Sri Lankan politics, as a more mature leader.

He may have got the top job not because of his political brilliance.

Still, he has seen much, been through even more and because of that, is a tough competitor, despite his modest and unassuming demeanour.

At 65 years of age and three years left of his first — and supposedly only- term of office — President Sirisena must surely be pondering his political future as well. He has pledged not to contest the Presidency again, even if it is retained and to go back on that pledge would shatter his credibility.

That would leave him with the option of running for Prime Minister from the SLFP where his potential rival could be Wickremesinghe, turning 68 this year. That is a prospect that neither of them will relish. Of course, the President also has the option of retiring gracefully after one term — but of Sri Lanka’s five previous Executive Presidents, only D.B. Wijetunga availed himself of that opportunity.

Pallewatte Gamaralalage Maithripala Yapa Sirisena must rally those around him from both sides of the political divide to ensure that when he leaves office — whenever that is — he hands over a country that is better off than what it was when he took charge.

To do so, he must do much better than what he has already done in his first two years in office. Or else, history would consign his era to the dustbin of mediocrity in much the same way that it has, in the opinion of many, judged the Kumaratunga Presidency.