Imaginative, allegorical and metaphorical too

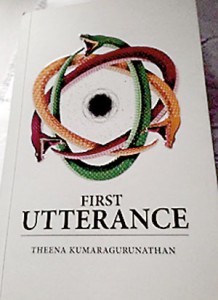

View(s): ‘First Utterance’, a self-published book by Theena Kumaragurunathan, has just been awarded first prize in the second Fairway Literary Award, in the English category. It is a breakthrough book, in several aspects: it is short, it is extremely affordable at Rs.150, it is a work of mythic fantasy fiction, it successfully incorporates elements of poetry, drama, satire and magical realism, and is the first volume in a story cycle. Above all, it is a self-published work, and this augurs well for future writers in Sri Lanka.

‘First Utterance’, a self-published book by Theena Kumaragurunathan, has just been awarded first prize in the second Fairway Literary Award, in the English category. It is a breakthrough book, in several aspects: it is short, it is extremely affordable at Rs.150, it is a work of mythic fantasy fiction, it successfully incorporates elements of poetry, drama, satire and magical realism, and is the first volume in a story cycle. Above all, it is a self-published work, and this augurs well for future writers in Sri Lanka.

I suggest that the judges of the 2016 Fairway Award should be awarded a Commendation Prize for thinking outside what has come to be seen over the past few years as the usual parameters of Sri Lankan literary culture to value a work of mythic fantasy. This award is literally a ground-breaking event.

The subject matter is epic. The back cover introduces us to ‘The story of three men, deemed mad in a dystopian world, who shirk reality for dreams, music for silence and sanity for peace,’ and urges us to ‘Plunge into Mirage as their collective fate brings a world to its knees and heralds the end of time itself’.

Most works of fiction created in Sri Lanka have been set in a world which is recognisable to us: contemporary reality, rural or urban social realism. This story immerses us, as the energetic exhortation ‘Plunge’ indicates, in a wholly otherworldly hyper-reality which is recognisable and accessible to us in an imaginative, allegorical and metaphorical way.

The other world created in this story is called ‘Mirage’ and its name evokes not only an oasis in a desert, a respite in a Wasteland, but Maya, Samsara, the illusions of this material world, from the Indian legends, which positions the realities experienced by human beings as occurring in a realm which is a testing ground for the soul. The characters, linked by their conditions of mental instability and problematic relation to the ‘real’ world, are on a quest. The outcomes of their quests are not predictable.

As I read, I sensed modernist and archetypal as well as apocalyptic aspects whirring simultaneously in the text. Huxley’s ‘Brave New World’ is invoked, and T.S. Eliot’s apt comment on the twentieth century as being ‘a vast panorama of chaos and anarchy’ is evocatively present, and there are distinct elements of prophecy resonant of Yeats’ Byzantium poetry – the unmistakable breakdown of one form of reality and the emergence of a new form – the need to create a new language to express a new condition of the heart and mind and spirit – to which the story provides access, and for which it creates a resonant vehicle.

This is the most transitional of times, in which we live: all the structures which formed and informed our lives and created continuity are being taken down and shaken off. The radical indeterminacy, the constant reactiveness into which we are compelled by rapidly changing external circumstances, the continuously interrogative nature of our response, is a highly stressful and volatile way to exist.

The inherent stress and distress of our human condition is perfectly expressed in Kumaragurunathan’s fusion of elements, and the dystopic society he delineates is permeated with the dissonance and discord which characterises our own world. Warring elements never really resolve into harmony. Tense exertion holds dualities in place, but we sense this will devolve into another form in the next phase. This friction and disquiet is reflected in the integrating vision which connects the structure, the imagery and the syntactical rhythm of the book.

| Book facts: ‘First Utterance’, by Theena Kumaragurunathan. Reviewed by Devika Brendon |

The book is a medley of utterances, and the first is female: Mirage herself speaks, in the form of a Mother, a Cosmic Mistress, counterpointing the book of Genesis and the imposition of order on primordial chaos. She, with her female energy, pre-empts and pre-dates patriarchy.

The female human figures in the rest of this story cycle will I hope take their cue from this multi-dimensional inception: most women in contemporary fiction are presented almost exclusively as vessels and objects of sexual release for the men. In an alternate universe, a more evolved state of relating would surely be imaginable between the sexes. The creating vision in Part V is a blend of strength and gentleness, an antidote to testosterone-fuelled Shock and Awe:

‘We heard a voice from atop Peak, the voice of a woman – so powerful that all of Mirage could hear her but so gentle that it blew out the flame of fear in all of us.’

The three tribes evoked in the story, each with their patrilineal lineages and books of scriptures, allegorically envision the political struggles of people from different faiths and belief systems to co-exist in one land.

The big picture offered to us of struggling human beings, with its potential for chaotic veering and derailment, is grounded by the stories of variations on the nuclear family: a father, his wife, his daughter, Adi. His detailed concerns about how he can protect and sustain them.

In the section ‘Naming The Nameless’, we meet Anne, whose husband, ‘one of the outspoken critics of President Mahasen’s administration, particularly the little-debated but speedily-enacted Psychological Cleansing Act 2190 that targeted the mentally frail’, had been made to ‘disappear’.

On February 2nd, 2222 President Mahasen VIII apologises for acts of violence committed against citizens by his father, the previous President. This section of the story is so poetic that it conflates myth and reality into wholly specific and original political satire.

The divergent elements and rapid scene shifts move us into close-up and then back up again to panorama, and the author’s narrative control is powerful, because it is inter-aligned, segmented, and flexible. The tone is temperate and detached. Nothing tips into chaos.

Imagistic elements such as The Peak of Butterflies and the empty Emergency Room rest interred in our minds, as we read, in the cubic centimetres of space that remain our only possession, in Orwellian-speak, and which are under threat in an era in which not only people’s ethnicity or religion are targeted by those in authority, but their personal mental and emotional states.

The cast of characters includes a President (Mahasen VIII), a mass of journalists and editors, and administrators, doctors and staff of asylums and hospitals for the mentally aberrant. Could there be more appropriate people presiding over the ending and beginning of worlds? There is also a Chorus, mediating between the action and the spectators, and entertainingly operating as a nervous MC, so frequently interrupted he finds it difficult to do his job.

In the last sequence of this story, the President throws his broken wristwatch into the bonfire in which the Book of Mirage is burning. With, as is the manner of Presidents, a few, well-chosen words:

‘And when it ends, those of us who have the task of sitting idly by have already made our choice because we know things end. Everything ends, doesn’t it? Things just stop working for no rational reason. This hasn’t worked in the 19 years, 43 days and 18 hours since you died. It is the way of the world. Everything ends. And yet, I didn’t stand idly by. I stood up and fought against forces you couldn’t imagine, old man. I tried. And I failed.’ He looks up and sees all eyes upon him.

It is refreshing to hear the words of this mythic President deal not with war or economics but existential philosophy!

The Miragian Cycle has started to spin. A testing ground in which we see the universe we used to think we knew become a multiverse in which we see ourselves reflected more fully.