Pride and tragedy

Unsung hero: Ananda Samarakoon

During the much abhorred mathematics period in the Wewala Government School, seven-year-old Egodahage George Wilfred Alwis Samarakoon took refuge in his own lyrics. Preferring the river which flowed by the school to his sums, young Samarakoon immortalised it in verse to the fury of the mathematics master. The punishment was to sing his own lyrics for the entire class! This in fact, was his entry to the world of aesthetics.

Egodahage George Wilfred Alwis Samarakoon (later Ananda Samarakoon), was born a Christian to Samuel Samarakoon who was then the Chief Clerk to British-owned Maturata Plantations and Dominga Peries on January 13, 1911, in Watareka, Padukka. He was the second of four sons. After his primary education at Wewala School, Samarakoon was admitted to Christian College in Kotte during which time he sent his entry to a lyrics competition organised by the Education Department. The lyric which opened with âapi wemu eka mawakage daruwoâ clinched the silver trophy and was later published in an anthology of lyrics titled âKumudiniâ. Returning from Shanti Nikethana in India in the late 1930s, he not only changed his name to Ananda Samarakoon, but also embraced Buddhism.

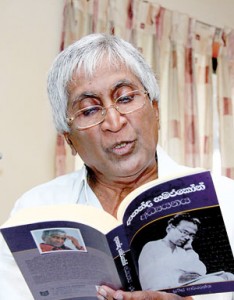

âNowhere else in the world had a creator of a national anthem been meted out such injustice as much as Ananda Samarakoon had,â reflects Prof. Sunil Ariyaratne, the eminent scholar. Donning multiple hats of linguist, researcher, lyricist and script writer, he has done extensive and little known research to date on the Father of the National Anthem. His book- Ananda Samarakoon Adyayanaya (Ananda Samarakoon – A Critical Study) navigates the life of Ananda Samarakoon from his birth to tragic death and offers a comparative study of several other national anthems across the world.

With the dawn of the British colonial era in 1796, the national anthem of the island was âGod Save the Kingâ. The national flag was the British Flag. As Prof. Ariyaratne points out, âthe colonial manacles were not so easy to shedâ, so much so that even before the commencement of theatrical productions of eminent dramatists such as John de Silva who produced satires on the British value system, âGod Save the Kingâ was sung. âHowever with the independence struggle getting intense towards the late 1930s, there was a revival in patriotic lyrics among which some so called ânational songsâ were also not uncommon,â says the scholar citing the lyrics of Ven S. Mahinda, M.G. Perera, J.P. Welivita, C.W.W. Kannangara and Ananda Samarakoon as some of them. âThere was no agreement on a national anthem as such, so much so that from 1943, The Ceylon National Congress sang its own anthem composed by D.S. Munasinghe. âIt was around this time the record under His Masterâs Voice label was released with Ananda Samarakoonâs namo namo matha. Among his other best known lyrics include ese madura jeewanaye geetha, vile malak pipila, besa seethala gangule and manaranjana darshaneeya lanka.

With the debate over the national anthem becoming more intense each day, a committee representing Sri Lanka Ghandharwa Sabhawa was appointed to organise a contest. Although Ananda Samarakoonâs ânamo namo mathaâwas submitted for the contest by his wife Caroline Samarakoon in 1948, he was in India at the time. In a bid to heal his broken heart after the tragic death of his five-year-old son, Ranjith Arunadeepa, Samarakoon found himself to be a Bohemian artist travelling all over India, holding not only successful art exhibitions but receiving invitations to adorn the covers of some of Indiaâs much acclaimed publications. As Indian critic Jasmine Roy once noted: âthere is something of music in his paintings: though the colour harmony is muted, his lines have all the charm and rhythm of Indian Ragas.â

Prof. Ariyaratne leafs through his book. Ananda Samarakoon- A Critical Study. Pic by Indika Handuwala

Interestingly, the winner of the national anthem contest was not Samarakoon but P.B. Illangasinghe. The music for his lyrics was by Lionel Edirisinghe. As Prof. Ariyaratne explains, it was this Illangasinghe-Edirisinghe collaboration which was initially broadcast as the official national anthem. âThe euphoria was short-lived as many challenged the validity of Illangasingheâs anthem since he too was one of the judges of the selection committee.â Samarakoonâs namo namo matha which was more popular among people by this time was eventually sung as the national anthem at the second Independence Day commemoration in 1949 in Torrington Square by a group of Musaeus College girls trained by Fr. Marcelline Jayakody. What is even more significant was the fact that the Tamil translation of the national anthem for which Pandit M. Nallathambi is credited was also sung on the same occasion. The commemoration notice printed at the Ceylon Government Press endorses, âNational Songs in Sinhalese and Tamil to be sung on the occasion of the Inauguration of the Independence Memorial Building at Torrington Square.â

In the wake of the recent controversy over the âprospectsâ of a Tamil National Anthem, historical evidence of this nature is imperative, says Prof. Ariyaratne who supports his research with historical evidence that singing the Tamil version of the national anthem was customary and even the government text books in Tamil incorporated this. âSadly this custom had a natural death. However, there was nothing controversial about it as the Tamil version did complete justice to the original lyrics and there should not be any controversy in reviving the tradition,â observes the scholar who further notes that national anthems rendering multiple linguistic flavour in multi-ethnic countries are not uncommon across the world.

With the debate over an officially sanctioned national anthem for independent Ceylon raging, The Times of Ceylon in its August 1st edition in 1951 made headlines to the effect, Decision soon on National Anthemâ. Accordingly the Cabinet decision to declare Ananda Samarakoonâs namo namo matha was officially announced in newspapers on March 12, 1952. Two years later His Masterâs Voice label, produced by the Cargills Company was entrusted with the production of records with the official anthem which had music and vocals by the Eastern Orchestra of the Radio Ceylon, Army Band and the choir of the then Blind School in Seeduwa. As a gesture of honour, the government decided to award Rs. 2500 to Ananda Samarakoon.

The first storm against Samarakoon loomed when P.K.W. Siriwardene claimed that the ârewardâ should be legally his as Samarakoon had sold the copyright of the publication Kumudini (an anthology of lyrics prescribed for school children by the Department of Education) in which namo namo matha was included. The irony was, Samarakoon was away in Madras involved in the production of the film Seda Sulang, meaning, devastating gales! A man destined for such gales in life, Samarakoon lost the case against Siriwardene. In February 1956, the state awarded Siriwardene the cash reward of Rs. 2500 and acquired the copyright of the lyrics.

The cross Samarakoon had to bear as the architect of the national anthem was exceptionally heavy. âWith the Bandaranaike regime coming into power in 1956, an anti-Samarakoon campaign was underway, alleging namo namo matha brought ill-luck. The extremists argued that political tragedies including the death of D.S. Senanayake, the  downfall of Sir John Kotelawala and later the assassination of S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike were all by-products of an ill-fated national anthem starting with an inauspicious syllable of ânâ,â explains Prof. Ariyaratne. In 1961 without any consent from its creator, namo namo matha was replaced with Sri Lanka matha.

Ananda Samarakoon the artist

Devastated, Ananda Samarakoon in a letter to Dudley Senanayake on March 3, 1962 hinted of his impending end stating that the act of altering the national anthem during the Sirimavo Bandaranaike era was nothing but a beheading of the same. He further noted that death was more merciful than life under a merciless regime. Exactly a month after this declaration, Samarakoon took an overdose of sleeping tablets on April 2, 1962 and was pronounced dead three days later at the National Hospital. He was just 51 years.

A man rich in all artistic faculties, was made poor by forces that worked against him. Ironically, Samarakoon was lauded only after his tragic death. âThe Cultural Department which gave him stepmotherly treatment took all measures to give him a âculturedâ farewell at the National Art Gallery, the first instance where an artisteâs remains were kept at the place. This act of hypocrisy was vehemently condemned by the press at the time,â reflects Prof. Ariyaratne.

The unsung hero he was, Ananda Samarakoonâs ill-fated life is best mirrored in Piyal Wickramasingheâs reflection for the Rividina paper of April 8, 1962: âSamarakoon did not die. We killed him. The government together with a few pundits killed him in cold blood. He is among the dead and we are among the killersâŠ.â

The Lankadeepa cartoon of August 26, 1955 lampoons the robbing of the National Anthem from its rightful owner, Ananda Samarakoon. (Pix from Ananda Samarakoon- A Critical Study by Prof. Sunil Ariyaratne)