Wearing off

A fast disappearing sight: Cobblers stick together hoping for more business. Pic by Indika Handuwala

Under the flyover in Dehiwala right next to the bus stop sits Michael Savarimuttu in his striped blue T-shirt and shorts, busily mending a cobalt blue umbrella with pink flowers. Thirty-two-year-old Michael is a father of two girls and works as a cobbler to make ends meet. Having no qualifications to speak of, Michael feels he is forced to make do with this work, although he begs us to find him a proper job so that he doesn’t have to suffer under the sun.

A few decades ago, they were a common sight but now they are a disappearing breed as it becomes more and more difficult for the street cobblers to survive. With each cobbler charging between Rs. 100 and 250 to fix a pair of shoes and a daily income of Rs. 600 to 1500 on average, most barely manage to make ends meet.

Among the line of about ten cobblers busily mending shoes is 39-year-old Mohammed Amir Mohammed Noorthy who takes pride in this humble trade. “I saw people fixing shoes when I was small and I thought I also could earn money like that,” he says. Charging around Rs. 100- 150 to fix a pair of shoes, Mohammed stresses that he doesn’t want to charge extra for fixing shoes because he feels it isn’t right to cheat people.

This father of three also works at Abans as a cleaner at night because the income he earns as a cobbler is not enough to get by.

Opposite the road from him is 51-year-old W. Nihal. His stall behind to the bus stop in Dehiwala seems to be losing him business and he complains that the buses block people’s view of him, although unwilling to move either. Next to him sits Wijeya Rathnapala who echoes the views of Mohammed and Nihal. This father of four also works at Abans at night, and says that Abans pays more than he can ever earn by fixing shoes, which led him to work as a cobbler during the day to earn a few extra rupees. Only a few people get their shoes fixed now because they opt to buy a new pair instead, he says.

The cobblers all next to each other leads one passer-by to remark that they would get more business if they were to spread out. Hearing this, another cobbler indignantly explains that there are many benefits in sticking together. “If we stay in one place even if one of us is unable to come on a particular day, the rest will be here. People know for sure that they can come here and find at least one of us to fix their shoes,” he explains. It seems that his logic is sound because many people around the area seemed to remember the Dehiwala bus stop as the place to find a cobbler (or ten!).

Speaking to the few people who have given their shoes, umbrellas and bags to be mended a rather sorry picture emerges. Although many people would get their shoes fixed by cobblers a few decades ago, that doesn’t seem to be the case today. Owner of the flowery blue umbrella being fixed by Michael, housewife Manel Wijenaike explains why. “I only fix things if there’s a small problem and it doesn’t cost too much. These people charge Rs. 100-150 to fix shoes. For that price, I’m better off buying a new pair,” she feels.

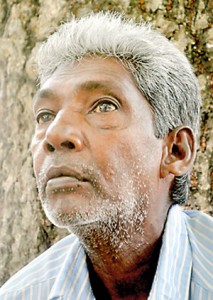

Mohammed Noorthy

Sampath Perera, an employee at Siemens shares a similar view. He says he rarely comes to get his shoes fixed because he only has the time to get them glued and this never lasts. However, he seems sorry for the plight of the cobblers. “We must go to them, otherwise how will they live?” he asks.

Under the shade of a tree opposite the Asiri Hospital in Narahenpita sits 61-year-old Mahith Paneer. Mahith used to work at an audit company but now after retirement fixes shoes. Business now is better than it was when he started around 10 years ago -as shoes, bags etc. are not made to last. “People come with 2 – 3 umbrellas a day. Some complain saying that they haven’t even used it for a week,” he says.

Although 56-year-old M .S. Fernando earns less than Rs. 500 daily from his stand in Panadura, he still feels that there is more business comparatively because shoes are expensive now. “Dan rate thiyena arthika thathwaya anuwa minissunta aluth sapaththu ganna salli na (because of the state of the economy in the country people don’t seem to have enough money to buy new shoes)” he says. The bus stop behind him makes his stand a good place for business.

Fernando also feels that an honest day’s work is important – a value he hopes to instil in his four children. “We all die one day, there is no point in increasing my fees and cheating people,” he says.

Also in Panadura, W. Hemapala has been working for 30 years. He says that his children (two daughters) don’t treat him well or look after him although they lead a good life. He lives out of a cardboard box on the street in Panadura near the bus stop. He must support himself however he can and therefore he fixes shoes, he explains. Earning less than Rs. 900 daily, he says that there are days that he starves because business wasn’t good. As an asthmatic who needs frequent medical attention, Hemapala feels quite alone and abandoned. He laments that he has been getting sick from time to time and can’t always afford proper treatment. “Even recently I was discharged from the hospital,” he says, showing us the medical records.

Fifty-two-year-old Yoganadan has a shoe stand near the Gangarama temple in Colombo 2. He started helping in his uncle’s shoeshop when he was young, in the early 70s. However, with the open economy they found it difficult to compete with the prices of foreign products and began mending shoes instead. During the time of the war, the police had asked him to close his stand. Now he has very little pressure from the police but his fortunes had decreased. “I used to have more business a few years ago,” he remarks sadly.

The most prosperous cobbler we met is 38-year-old K.Ravindra. With his stand a few miles away from Panadura, he earns Rs. 2000 – 3000 on a good day, although he remarks that business varies sometimes. A trade learnt from his father, today he uses this skill to fulfil his own responsibilities as father of three children aged 15, 7 and 6 so that they can lead a better life than him.

With many cobblers who learnt the trade from their fathers seeming rather reluctant to pass the skill on to their children, this seems to be a dying profession. W. Nihal sums up the uncertainty of the trade. “Api balagena inna one kagehari sapaththuwak kadenakan (we have to wait until the shoe of someone walking past breaks)”.

Carrying on in a man’s world  C. Walli Fifty-nine -year-old C. Walli is a woman in a job largely dominated by men. She says she learned the trade from her husband for fun but when her husband passed away she found herself thrust into the role of sole breadwinner. She has five children – four girls and one boy, with her youngest still in school. “When I started, it was really hard because it’s difficult for a woman to sit on the roadside alone and wait. Now I have a hut here and it’s been a bit better but I still face issues,” she says, showing us the temporary structure she has erected behind a lottery ticket stand at the Narahenpita junction. She charges Rs. 250 – 300 for gents’ shoes and Rs. 150 for ladies. If you need a strap fixed, you can get it done for Rs. 20 – 30. Her services seem to cater more to the female clientele because she also fixes handbags – one of the few people whom we interviewed who did so. However, with earnings of Rs. 500 – 700 on a good day, she feels that this profession is difficult to live on. |

Mahith Paneer

Business is hard: W. Nihal in Dehiwala. Pix by Athula Devapriya