The mysterious Major Raven-Hart

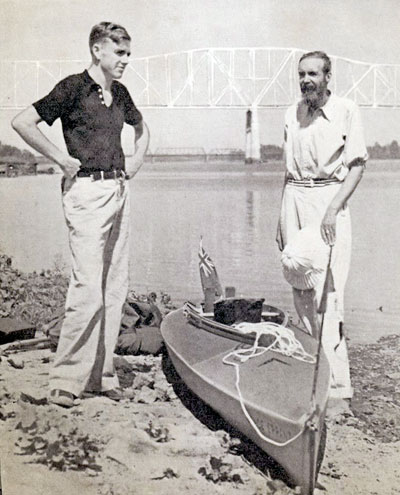

Raven-Hart the canoeist, at right. Pix courtesy callumjames.blogspot.com

Inevitably, following Independence many colonists left Ceylon. Yet during the first decade of freedom, the island attracted some characters of distinction that formed a ‘diminished band’ from Britain. In unexpected ways they contributed to the nation’s historical documentation, religious tradition, modern culture, and the positive perception of the nation abroad.

Prelude

The best-known, Sir Arthur C. Clarke, CBE, needs little introduction. He was an ambassador for Sri Lanka for five decades, whether riding an elephant along a beach while expounding on the glory of ancient Anuradhapura for a television series, or in some (too few!) of his writings regarding the island such as The Treasure of the Great Reef (1964), The View from Serendip (1977) and The Fountains of Paradise (1978). Just being a celebrated author resident here was a considerable contribution.

Michael J. Wilson, Clarke’s business partner and scuba-diving guru, accompanied the writer on early submarine safaris in the Indian Ocean guided by the semi-amphibian Rodney Jonklaas. Wilson evolved into Swami Siva Kalki, spending years in a kuti at Kataragama to aid Lanka’s spiritual protection before returning to Colombo, and passed away in his treasured adopted island in 1995, long before his ‘mate’ Arthur did in 2008.

The least-known was the somewhat mysterious, brave and brilliant Major Roland James Milleville Raven-Hart, OBE, an intrepid intelligence agent, pioneering radio engineer, adventurous canoeist and diligent translator of historical texts – the latter his most important contribution to the island, together with a distinctive travel book and lauded account of the Buddha’s pilgrimage.

Without Raven-Hart, Clarke might not have decided to reside in Ceylon. The Major (he prefaced his name with his rank until death except during World War Two), a resident since 1947, had arranged to meet Clarke when the ship taking the writer to Australia docked for a half-day at Colombo in 1954, and no doubt influenced the writer to experience Ceylon, which he did with Wilson in ‘56.

During our friendship from 1973 until his death in 1995, Wilson/Swami Siva Kalki sometimes spoke of Raven-Hart and showed me two items that the Major had gifted him before his departure from Ceylon in 1963. The first was an edition of Venus in Furs (see “The tale of another tale – Venus in Furs”, The Sunday Times, August 1, 2010), the second an original Disney artwork of Donald Duck celebrating 1951 in a scientific manner (electron valve and formulae leaping from his brain, etc.).

The quest for Raven-Hart

I knew too little concerning Raven-Hart for any kind of biography. A request, “Looking for friends of Major Roland Raven-Hart”, in The Sunday Times of February 7, 2010, brought forth many replies both local and international. Many were from canoeing enthusiasts. Two such, Wayne Wegner (Canada) and Dr James Palmer (UK), joined me in investigating Raven-Hart in some, but not exhaustive, detail. Others from elsewhere provided invaluable assistance, including a prime exhibit – a copy of his passport from 1935 to 1949 with vital information about his movements in his spy era – acquired by Hugh Karunanayake in South Africa.

Raven-Hart, according to his British passport, issued “By His Majesty’s Consul General at Marseilles on the 19th day of September 1935”,was born on November 13, 1889, at Glanalla (sic) – Glenalla, County Donegal – Ireland, “A British subject by birth”. His profession is given as “journalist”. He had a sister, Hester Margaret Emilie Raven-Hart, born in 1896 in Scarborough, Yorkshire, England.

They had as parents an English father, the Anglican Rev. William Roland Raven, and Irish mother Edith Hester Maria O’Neil Fairbrother. Roland is sometimes rendered as ‘Rowland’: this appears to have originated in America and has been perpetuated by transcription. He mostly reduced the name to the initial “R”, evident in book titles. That his father bore the name in Roland form resolves the matter. In addition Milleville is misspelt ‘Milliville’ in certain documents. The classic “Raven-Hart” was created by the Reverend after marriage to provide Irish association to the union: his wife’s maternal grandmother bore the surname Hart, a noteworthy ancestry in Donegal.

The family ended up in Suffolk, England, where the Reverend was “instituted to the Vicarage and Parish Church at Fressingfield, with the Rectory and Parish Church of Withersdale, Suffolk, on the presentation of the Master, Fellows and Scholars”, as a provincial newspaper reported on February 5, 1907.

Raven-Hart probably entered London University around that time – other universities later in Paris and Berlin – ultimately receiving a Doctor of Letters in England and a Licencie es Letters (arts degree) in France. He served in London University’s Officers Training Corps and after the outbreak of World War One joined the Suffolk Regiment.

A heroic war

According to C.C.R. Murphy’s History of the Suffolk Regiment 1914-1927 (1928), in 1915 Raven-Hart was a lieutenant in the 10th Battalion of the Regiment, part of the Special Reserve Brigade, and appointed signal commander. Mentioned in dispatches, he was promoted to the rank of Major, joined or was affiliated with the French Army at some point and gassed in the battle of Le Cateau in 1918. He was also attached to the Royal Engineers and the Egyptian Expeditionary Force.

Assigned in 1918 to the General Staff under Lord Allenby, he commanded the 2nd Wireless Observation Group, responsible for wireless interception, and served undercover missions in France, Belgium, Russia, Italy, Palestine, Sudan, Syria and Egypt, where he installed an antenna on the Great Pyramid to improve communication. He is supposed to have rescued a party of nuns and consequently became acquainted with Col. T.E. Lawrence (“of Arabia”).

Probably before his hectic war, romance or attachment flourished between Raven-Hart and Rosemary Croft, born in 1891, and they were married in 1916 in Edmonton, London.

In 1919 he was honoured with the Order of the British Empire (OBE) “For valuable services rendered in connection with military operations in Egypt”. Furthermore, several allied governments honoured him, chiefly France with the Croix de Guerre and Russia the Order of St. Stanislaus.

Argentina: radio pioneer

Raven-Hart headed for Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1922 to make use of his skills in radio transmission (he was a member of the Institute of Radio Engineers and the American Institute of Electrical Engineers). He settled in the mountains and established a radio station, 9TC, which in 1923 accomplished the first reception between North and South America, a distance of 8,300 km.

Under the pseudonym John Inglés (“John English”: he was known as John to friends, including Clarke), he reported in the Buenos Aires Telegraph Magazine, October 1923 edition: “October 30 and 31 at night received the full program of a station that was announced as KDKA – Pittsburgh: classical music, jazz . . . The antenna was 20 m long by 5 m high on a zinc roof.”

According to his (then) current passport,the previous passport had been issued in Valparaiso, Chile (why he was there is uncertain) in 1926 in order to return to Europe. Yet in the passenger list his nationality is given as Irish. And in the Second World War, as will be seen, he initially revealed an affinity with Argentina, a country he knew for four years.

Canoe Errant

Raven-Hart is best- known for his canoeing marathons. Indeed he is one of the sport’s icons, who paddled some 29,000 km. His enthusiasm began in the early 1930s in France while living in Le Ciotat, an enclave on the Mediterranean, the population a mere 10,000 at the time. Subsequently in 1934 he purchased a collapsible two-seater canoe, 5 m in length, made of canvas and rubber, which he named “Canoe Errant”. It was manufactured by a German firm: Hart.

Between the World Wars and afterwards, Raven-Hart ventured down some of the world’s major rivers, which resulted in ‘canoe-logs’, the first being Canoe Errant (1935), set in France. It reveals Raven-Hart was an Esperantist: he relates how he gained information on rivers and ‘canoe stations’ from the Esperanto ‘canoe consuls’ along the way. The name Raven-Hart translates phonetically as “Raven-Heart”, and approximately as “Korvo-Cervo” and directly as “Korvo-Vicervo” in Esperanto.

The passport provides information regarding his more distant adventures. Five days after its issue he obtained a visa for Egypt, landing at Port-Said on October 17, 1935. There he obtained a visa for Sudan, where the Nile rises, arriving at Wadi-Halfa on October 26 to begin the journey that resulted in Canoe Errant on the Nile (1936).

In the late 1930s Raven-Hart wrote Canoe Errant on the Mississippi (1938), Canoeing in Ireland (1938), and Canoe to Mandalay (1939). He travelled extensively during the years 1937 to 1939.Austria, annexed by Germany, Sweden, (he wrote a booklet “Six Swedish Cruises”),and then, consecutively, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia.

He landed in Ceylon twice according to the Colombo Harbour Police, on November 14, 1937 and February 28, 1938 while visiting India, as there is the stamp of the Harbour Police Madras dated November 23, so most likely this occurred during the Mandalay trip.

Unquestionably the most important visa was granted by Nazi Germany in June 1939, just three months prior to World War Two, to canoe on the Danube. The visa was signed by the German Consulate in Venice, featuring the Nazi stamp with eagle and swastika – the same used in Schindler’s List (1993). It was such trips that founded the rumours that Raven-Hart was carrying out espionage during his canoe journeys.

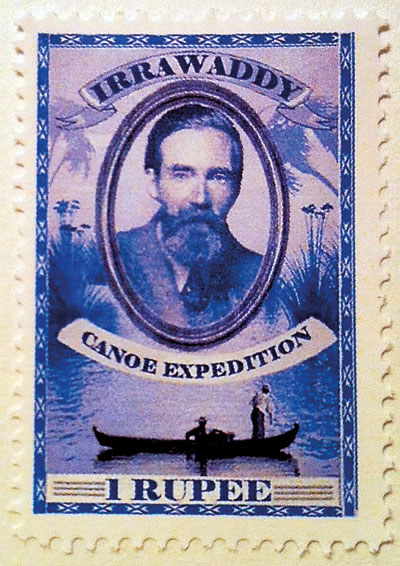

He became the first canoeist to traverse the length of Myanmar’s Irrawaddy, some 2,100 km, as recorded in Canoe to Mandalay. Mark Valentine and Colin Langeveld designed a fantasy 1 rupee stamp commemorating this feat, limited to 300 copies, which provides an excellent facial portrait of the man.The stamp “represents the private canoe courier label he might have issued for carrying mail to the settlements on the river banks”.

Young companions

His first book, Canoe Errant, revealed his partiality for young boys as companions on his expeditions and the probability he was a paedophile. Certainly his somewhat homoerotic accounts and photographs of young boys in loin-cloths don’t boost any denial. With these boys he canoed and swum naked; innocent enough maybe, but as Ronald Hyam states in “Empire and Sexuality: The British Experience” (Journal of Social History, Summer 1992):

The stamp issued to commemorate Raven-Hart’s Irrawady journey

“Wilfred Thesiger [the English explorer] enjoyed the company of Arabian youths, while the intrepid canoeist, Major Raven-Hart, was on equally close terms with Egyptian, Sudanese, Burmese and Sinhalese boys, writing up his adventures with an incidental candour about his relationships which would have rendered them unpublishable had they concerned British boys.”

In 2010 I received a letter from “NK” of Wattala who, apart from providing an excellent description of the Major – likening him to D.H. Lawrence – provides revealing observations of his attitude to, and effect on, young boys:

“When I was 14, my parents and I lived at the Hotel Savoy situated around Kandy Lake. Here the Major was also a guest. Although many years have elapsed, the name Raven-Hart has stuck in my mind. His gaunt appearance and height, and lean frame, gave the appearance of a very learned person. [Raven-Hart’s passport describes him as being 6ft 2in tall, with pale blue eyes and fair hair.] And I realized he was an author and an adventurer from his safari-type attire and his very private style of living while at the hotel.

“He also had a very piercing way of looking that scared me at that age. Later on he did get chatting with me if and when he was at the hotel: the main topic was about his trips into the jungle and canoeing that kept me enthralled and fascinated. Although there was a vast gap in age he seemed to like my company whenever he was at the hotel.

“There’s another aspect to the reason I could remember him, to this date, was his outstanding personality and slight beard that reminded me of two other famous people – that is D.H. Lawrence and Vincent Van Gogh, who I admired very much.”

World War Two

In September 1939 Raven-Hart was commissioned in the army as a second lieutenant, the lowest rank in the service, which must have prickled the former Major. For reasons unclear, he relinquished his commission just six months later in March 1940. Was he forced to? Perhaps, as he had been caught sending indecent photographs through the post around March, for which he was landed in court and convicted several months later.

The Yorkshire Evening Post of October 5, 1940 reported: “Censor fined. Indecent photographs sent through the post. Major Roland Raven-Hart (51), retired, of Guildford Street, Bloomsbury, said to be a sculptor and author, now employed as a censor at the Ministry of Information, was fined £l0 and £l0 10s costs at Bow Street Court.”

How he turned out to be a censor at the Ministry of Information is unclear, as indeed what occurred between then and April 1943 when he became one of 766 Argentinean Volunteers, mostly of Anglo-Argentine descent, who served in the RAF and RAFVR (Volunteer Reserve). He was a Pilot Officer in the Technical Branch, again the lowest rank in the service.

Why he decided to join the Argentinean Volunteers is also unclear. He served with 164 Squadron, created for the Argentine Volunteers in 1942, which was based in Scotland but a year later transferred to Wales. It was a fighter squadron involved in the Battle of Normandy before being disbanded in 1946. He wrote an amusing pamphlet “RAFing It: A Guide to Joining the RAF” (1944) under the pseudonym ‘L.A.C. Errant’.

At some stage he joined the Royal Indian Air Force and was stationed in Bangalore, where he taught pronunciation to staff, no doubt for radio purposes, and was possibly involved with radar training. He was demobilized in 1946.

“Major Macroo”

Raven-Hart’s wife Rosemary died in 1946. She was a friend of the British poet Stevie Smith (1902-1971); so was her sister-in-law Hester, for there is correspondence between them and Smith in the McFarlin Library of The University of Tulsa. But Smith disliked the way Raven-Hart neglected Rosemary, which prompted the poet to write “Major Macroo”, to be found in Collected Poems and Drawings of Stevie Smith (2015):

Major Hawkaby Cole Macroo

Chose

Very wisely

A patient Griselda of a wife with a heart of gold

That never beat for a soul but him

Himself and his slightest whim.

He left her alone for months at a time

When he had to have a change

Just had to

And his pension wouldn’t stretch for a fare for two

And he didn’t want it to.

He’d several boyfriends

And she thought it was nice for him to have them,

And she loved him and felt that he needed her and waited

And waited and never became exasperated.

His sister Hester died around this time and he proceeded to Australia, where he canoed from September 1946 to July 1947 before travelling to Ceylon. Canoe in Australia (1948) and The Happy Isles (1949), about the Torres Strait Islands in Queensland, were illustrated by his fine drawings and photographs.

Sojourn in Ceylon

Raven-Hart arrived in Ceylon in late 1947 and tested the waters of Sri Lanka’s rivers and canals. Sunela Jayewardene informs me her uncle, Dr Ray Wijewardene, kayaked with Raven-Hart down the Mahaweli. Raven-Hart was also an enthusiastic land-traveller who used bicycles and his feet, enabling him to write the outstanding Ceylon: History in Stone (1964). The dust jacket rightly states: “In this book we see the complete and the versatile man, the lover of men, animals and birds; the student of archaeology, religion and myth; hiker, angler, and canoeist, and above all, a friend of Ceylon and her people.”

Another notable local publication, demonstrating his interest in Buddhism, is Where the Buddha Trod (1956). In the Foreword the Ven. Nyanatiloka Maha Thera comments: “A book unique of its kind. To the research student in Buddhism it will serve as the kind of material that makes the Life of the Blessed One as a historical personage a reality.”

Arthur C. Clarke in The View from Serendip (1978) writes that Raven-Hart “easily tops my list of The Most Unforgettable Characters I’ve Ever Met” and likens him to Conan Doyle’s Prof. Summerlee from The Lost World (1912).

Tissa Devendra tells me Raven-Hart was a friend of his father, archaeologist D.T. Devendra, and “dropped in at home, and his office in the Archaeological Dept., for long conversations . . . He was over 6 ft tall and looked like D.H. Lawrence [a common comparison] with sunken cheeks and straggly beard. Father was convinced he had been a British intelligence agent and all his many travels combined pleasure and ‘business’.”

Raven-Hart was a remarkable linguist. He read a dozen languages and spoke five, making a significant contribution to Ceylon’s historical documentation with the translation of Heydt’s Ceylon (1952)– Heydt was a prominent colonial Dutch observer - Germans in Dutch Ceylon (1953), The Great Road [between Colombo and Kandy] (1956), Travels in Ceylon, 1700-1800 (1963), and The War with the Singalese (1964). He also transcribed The Pybus Embassy to Kandy, 1762 (1958). (Pybus was the first British envoy to meet the ruler of Ceylon’s independent Kandyan Kingdom in 1762.)

South Africa

On April 15, 1963, Raven-Hart surprisingly departed his beloved Ceylon for South Africa after a residence of 16 years. According to Clarke he left for financial reasons; not totally convincing as he lived until his death in 1971 in what must have been a more expensive country. Speculation: perhaps some pending scandal influenced his decision.

More positively, as the jacket of Ceylon: History in Stone declares, “he may be considered as the last of the long line of illustrious foreigners whose writings on Ceylon are now part of her history”. Residing in Durban, he continued his historical translations. For instance, he was able to pursue his interest in Heydt (who had served in South Africa before Ceylon) by translating and editing the text of the German’s Scenes of the Cape of Good Hope in 1741 (1967). He also translated and edited Cape of Good Hope, 1652-1702: the first fifty years of Dutch colonisation as seen by callers (1971).

Raven-Hart’s sister, Hester, co-authored with Isabel Chisman Manners andMovement in Costume Play (1934). With Hester he wrote This to the Queen (1950) about Shakespeare’s Hamlet. He also co-authored an article, “Wireless Music”, with the British composer Sir Lennox Berkeley in The Nineteenth Century (1930) and, demonstrating his interest in pottery, “The Beater and Anvil Technique in Pottery Making” in the American Anthropologist (1962).

Raven-Hart has critics due to his apparent moral laxity; nevertheless, he remains an important post-colonist in his contribution to the understanding of outsiders’ literary accounts and his own distinctive writing on Ceylon, not forgetting his influence on Arthur C. Clarke to reside in the island.