News

Village tank project provides lessons for restoration

View(s):By Malaka Rodrigo

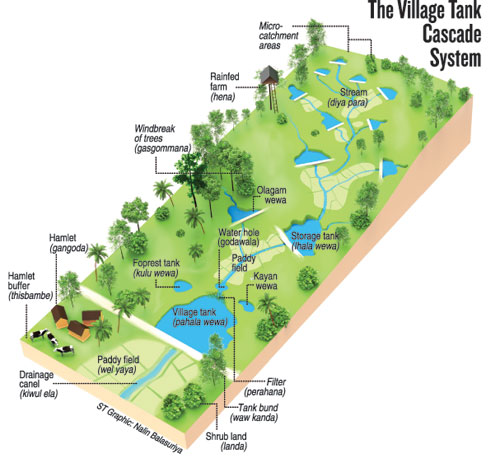

Sri Lanka is famous for its irrigation heritage, but only the marvels of large tanks built for irrigation draw attention, while small village tanks are ignored. In many cases village tanks function as a ‘cascade system’ – so using wrong methods to restore them ignoring specific functions of associated components can do more harm, according to experts who discussed the issue recently in Colombo.

People engaged in building an irrigation canal. Pic by Kumudu Herath@IUCN

The International Union of Conservation of Nature and Department of Agrarian Development together with Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies, shared their experiences under the theme “ecological restoration and sustainable management of small tank cascade systems,” on February 14.

The experts say that in Sri Lanka’s dry zone there are 14,000 small ancient village tanks and many are in good shape, supporting 246,000 hectares, about 39 percent of the total irrigable area. In most cases these tanks are designed to function as interconnected clusters often referred to as ‘cascade systems’ called as ‘ellangawa’ in Sinhala.

These tank cascade systems are identified as very efficient water management systems in the world with water being recycled in each tank without letting it go to waste. The entire tank system functions as a single unit, so restoring only a single tank is not useful, said IUCN’s Program Coordinator Shamen Vidanage.

Each tank in a given cascade system adopts geographical and functional features to harmonise with nature. The functional components of a tank perform specific purpose and roles of these components can even be explained in modern science although they were designed centuries ago, he added.

The first set of components of the cascade system is designed to improve the quality of water entering the tank from the catchment.

‘Kulu wewa’ also known as the ‘Forest Tank’ and water holes known as ‘harak wala’ and ‘goda wala’ are all located in the catchment of the tank, retaining dead leaves, mud and other debris, or sediment, experts explain. Next, before the tank is grass cover known as ‘perahana’ located between catchment and high flood levels for purifying the water by holding granules of earth, and sediment functioning similar to a preliminary treatment step of a modern waste water treatment system, the experts explain.

The water stored in the tank is protected from evaporation by tree belt naturally growing on either side of the uppermost areas of each tank. These are called ‘gasgommana’ acting as windshields minimising dry wind contacting the water surface minimizing evaporation, the experts note. “Kattakaduwa’ or interceptor, is a thick strip of vegetation located between tank bund and paddy fields. It also has a water hole called ‘yathuru wala’ to retain saline water seeping from the tank. Various plants of salt absorbing features are found on ‘kattakaduwawa’ which reduce the salinity of the water seeping through the bund before it reaches the paddy fields, the experts say.

“Sadly the cascade systems are poorly understood. For example, there are instances that forest tanks have been used for irrigation,” Vidanage points out.

“Sadly the cascade systems are poorly understood. For example, there are instances that forest tanks have been used for irrigation,” Vidanage points out.

“Every village had a patch of forests called as ‘gam kele’ and that has disappeared as they are being encroached for agriculture. As a result of these wrong land use patterns, these small tanks now get more sedimentation, increasing tank siltation,” says Professor C M Madduma Bandara of the University of Peradeniya.

Tank sedimentation due to soil erosion is the main factor in the deterioration of the cascade system. Silted tanks retain less water and over the years, these tanks dry out and paddy fields are lost experts say. In addition, pesticides and fertilizers applied in upper areas pollutes the tank water without getting proper natural filtering mechanisms. So experts fear that in future, many of these tank cascade systems will deteriorate and will be abandoned owing to mismanagement.

Meanwhile, as a pilot project, IUCN partnered with Department of Agrarian Development to ecologically restore the Kapiriggama small tank cascade system in the Anuradhapura District. This three-year project was initiated in 2013 with financial assistance from the HSBC Water Programme.

Kapiriggama cascade is in the basin of Malwathuoya and consist of 21 tanks. During the project over 38,000 of cubic metres of silt was removed from five tanks in the Kapiriggama and the removed silt was deposited upstream IUCN says. The project also setup soil conservation mechanisms building soil conservation bunds. Over 7,500 plants on kattakaduwa on 13 tanks were also planted according to IUCN.

“We have also got community participation for all these tasks, so even when the project finishes the villagers who will benefit will be engaged making sure of the sustainability of the Kappirigama tank cascade system,” Dr Ananda Mallawatantri the Country Representative of IUCN said. The north central canal project can also use cascade systems in its design taking additional water into cascades before providing to paddy fields, Dr Mallawatantri said.