Sunday Times 2

The man whose quiet ways touched many

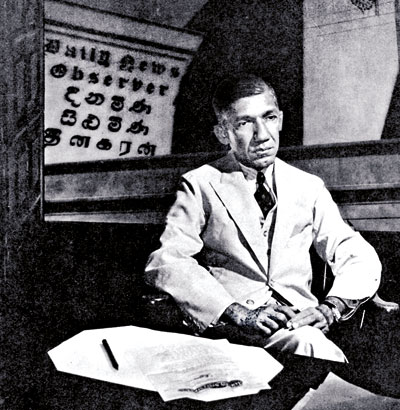

View(s):The 131st birth anniversary of D.R. Wijewardene fell on Thursday, February 23

By E.E. C. Abayasekara

Of D.R. Wijewardene the visionary and patriot, who, single-mindedly bent all his efforts towards securing freedom for his country; of how in the process of achieving what he did achieve he created a remarkable newspaper organisation, and of the numerous benefits it brought the nation– these have been told before, though they can still bear retelling on occasion.

There are some sidelights, though, of Wijewardene, the man, not recorded in his biography, which seem worth the telling, if only to supplement what has been written. Others too will doubtless have their own stories to relate of their encounters with him.

In the nature of things, public figures tend to receive bouquets as well as brickbats, sometimes more sometimes less of the kind they deserve. D.R. Wijewardene was no exception.

As his biographer points out, he was no superman, and was subject to the frailties that flesh is heir to. But there were also certain features one notes, in his life and character as a man, and if, on occasions such as this, they come to mind, they can also have their values in the telling.

As his biographer points out, he was no superman, and was subject to the frailties that flesh is heir to. But there were also certain features one notes, in his life and character as a man, and if, on occasions such as this, they come to mind, they can also have their values in the telling.

My first encounter with D.R. Wijewardene left a deep impression on me of the man himself, an impression which even the many subsequent much closer encounters in the work-loaded pressure-packed 15 years during which I worked for him, did in no way diminish: the impression was of a man essentially simple and straight-forward, and also possessed of an understanding nature.

The encounter was in 1934 when, being interviewed by him for a junior clerical post at Lake House, I had questions to ask of him myself, and which, with the directness and brashness of a 19-year old, I did.

“Will I have opportunities for advancement?” – “Yes”. “How far can I go?” – “Well, that will depend on you; you can rise to be manager”.

“And what is the manager’s salary?” – “Rs. 750″.

Direct replies, but their significance lay in the manner in which they were given; quite simply and straight forwardly, as man to man, not savouring of an employer-employee relationship.

Within days of my taking my seat at an office desk at Lake House, it was brought home to me convincingly that the almost quiet man who had spoken to me so simply, was the power-house in many senses, of the powerful institution he had founded and over which he presided.

That same simplicity and straight-forwardness were, I was later to find, basic to the man and were characteristics he also looked for and valued in others.

Writing of him in 1964, his biographer, H.A.J. Hulugalle, reputed for his balance, fairness and good judgement, said: “It is probably correct to say that no Ceylonese during the present century exercised a more pervasive influence than he did.”

How then, it may be asked, were there so few in the country who were aware when he died, of who D.R. Wijewardene was, and what he had done; not only of his outstanding contribution towards the attainment of political independence, but, through his newspapers, in the spreading of education, the stimulation of political and social consciousness, and a greater awareness of our national cultural heritage.

The answer is, I think, to be found in what must seem a deliberate self-effacing policy he adopted, the studied avoidance of personal publicity; not only because he happened to be a naturally shy man, but mostly because, I am sure, he was persuaded that, where great causes were concerned independence, press freedom, the public interest persons should always be subordinate, publicitywise to the causes they espoused.

As a leading newspaper proprietor by any standards in the then newspaper world, he was very much in the centre of things in newspaper councils of his day, and thus in demand to propose or respond to toasts and the like at such gatherings abroad, something he was most averse to accepting, unless it was necessary to.

In a letter to Herbert Hulugalle in 1937 he refers to one such occasion. He wrote: “I am strongly hesitant, but they are insistent. I haven’t given my final word… If I agree in a weak moment, it will simply be for the greater glory of Lake House. Reuter might send a cable about the dinner, and if my name is there, make a judicious splash for the sake of the newspapers. No photograph.”

True, circumstances, styles and conventions in these matters have changed with the years, but the principle behind Wijewardene’s approach to propaganda for causes and personalities is clear enough, and point to certain basic moral values which can be lost sight of.

In the complex task he applied himself to of organising and co-ordinating the forces in the country which had their sights on self-government, and later, in building up from scratch and un-doubtedly, great odds, an extraordinarily large newspaper organisation, Wijewardene must have inevitably been confronted with as large a body of problems and crises as anyone.

It is a matter of history that he surmounted these. That some of those who came in touch with him towards the latter years of his life when new complexities had developed and age was catching up on him, saw at times only an impatience and querulousness in his approach to situations, would be natural; but this was by no means his normal reaction.

In fact, times of stress and difficulty, I observed, seemed to stimulate some inner resource in him, and I have seen him almost looking forward to grappling with difficulties he was anticipating.In the 1915 riots, he had as an officer in the volunteer service, and at one time as a suspect of the military authorities, cause enough for anxiety and concern.

In letters he had written at the time to his fiance, couched in simple unaffected terms, his biographer found evidence of “a simple and sincere character even in the midst of civil turmoil and personal emotion.”

Whilst his perfectionist tendencies were by no means matched by as expansive a patience in day-to-day matters, he never seemed in time of real crisis to lose his cool. Whenever he had occasion to have a strong letter prepared, and one which he suspected might have been influenced more by emotion than reason, he had a practice of laying it by to be looked at afresh after 24 hours in a more settled perspective.

One occasion I still remember because it struck me as extraordinary at the time, was when Wijewardene was to be summoned before the Select Committee of the State Council on a charge of breach of privilege, and it was known that an attempt was to be made to humiliate him.

He was normally not given to genial smiles when it came to getting on with the work. But that morning I found that the usual look of concentration had given way to a smile, with a hint of mischief in it. Rolling up his sleeve – an unconscious mannerism of his when he was impatient to get his teeth into something in earnest – he remarked: “This is going to be fun I am waiting to give it to them!”.

However, we were denied this bit of fun, as the inquiry fizzled out. Seeing that the issue which led to the charge had something to do with his on-going battle for freedom of the press, a cause always close to his heart, I could understand he was spoiling for a fight, and threats could in no way daunt him.

The impression that Wijewardene was a heartless man who set work and efficiency above all else seems to have gained ground, apparently through stories passed around by word of mouth. Certainly he did set high standards of work, application to work and efficiency, and he was by no means tolerant of negligence and carelessness, nor was he inclined to suffer fools gladly.

It has to be said though that such attitudes are not uncommon to perfectionists, and he was in fact a supreme example of that breed.

On the other hand, he was, by and large, a fair employer, and, when the business prospered, a generous one, especially perhaps to those who worked well for his organisation.

Provident Fund and employee shares schemes were initiated by him many years in advance of most businesses.It is also to be borne in mind that being the man he was, Wijewardene was not the one to publicise his acts of kindness and consideration, whether done in the office or outside.

A young man who was noticeably underweight, found one day that the “Boss”, as the Managing Director was called among the staff, had arranged for him to have a glass of milk daily in the afternoons, this being brought in the “Boss’s” car when he came in about 3 p.m.

I know because I happened to be that young man. When he came to know that I had planned to go upcountry on my annual holiday, he quietly slipped me a generous cheque mentioning it could be used for warm clothes which he knew I would need. Always the gentleman, he did so without the least hint of patronage, so one sensed it did come from the heart.

I am sure there were others, who would have experienced similar gestures of kindness, not necessarily in money.

In Wijewardene’s philosophy, work and play did not mix; each had its role and place. Thus, if he gave short shrift to those he was satisfied had been guilty of lapses or negligence, he also gave every encouragement to those who displayed an intelligent interest in their work or showed any initiative.

It was extraordinary how amidst all his responsibilities and work – from giving his mind to questions of public interest, and to all the multifarious activities involved in the running a newspaper organisation – he still found the time to enquire into the progress of and to help even junior staffers in different departments, in various ways: suggesting ideas for short articles, lending magazines, and drawing them out in conversation.

How he managed to do all this, from memory for he had no system of keeping notes – always amazed me. Equally surprising was how he managed to ferret out information about problems some of the staff he was particularly concerned about, were up against, in order to give thought to what might be done for them.

In one case when he found that a young man who had applied to join the establishment as a trainee journalist, was doing so as he had to abandon his studies owing to the lack of funds, he agreed to finance fully this young man’s studies at the University for three years; if he won the Government University scholarship he was free of all obligations, if not, he was, as he earlier asked for, to join Lake House.

As it happened, this young man, after finishing at the University became a member of the editorial staff, was later sent for work experience on leading newspapers in the UK, and year later, after Wijewardene’s death occupied the editorial chair of another well-known English newspaper. Benefactors are, it seems, sometimes found disguised.

Events, descriptions of life at Lake House, and the hand he took in public affairs, which are related in his biography give some insight to Wijewardene, the man. These include recollections of life at home contributed by his daughter, Mrs. Nalini Wickremesinghe.

The following short extracts give an interesting picture of the Wijewardene family at home:

“Often the family sat around in the study-curled up in his enormous armchair, scribbling on his blotter or delving into the drawers of his desk with childish curiosity. There was so much interesting material – long letters on political reforms and controversies dating back to 1915, newspaper cuttings, newspaper attacks, letters containing congratulations, resignations, all carefully folded and put way…

“In spite of his being deeply absorbed in political and newspaper affairs he always found time to help my mother with her household problems, to play with the current baby of the family, to follow school activities, end of term reports, to take us along with him to the dentist and to plan out interesting holidays and outings for the family.

“He never failed to discuss the happenings of the day with us and to make us wildly enthusiastic over battles the newspapers waged at different times.”At the end of a long day’s work he would sit at the head of the dinner table and explain the current political situation, and though we were scarcely in our teens, he would ask us for our views!”.

Outstanding characterstics of Wijewardene, evidenced or glimpsed in the events or accounts published in his biography include his integrity, self-discipline, tolerance and liberal approach in most things. Perhaps this is why his biographer, his closest associate for over 30 years, concluded the biography in these terms:

“Whether democracy will succeed or not in Ceylon will depend even more on the character of her leaders than on their courage or capacity. The lesson of Wijewardene’s life is that men can achieve great things for their native land if they have faith in the future and are prepared to work for their ideals with self-discipline and tolerance.

(This article first appeared in the Daily News of February 22, 1986. The writer who rose to be a director of Lake House served long and closely with Mr. D.R. Wijewardene.)