Alice in Wonderland: A children’s tale or discourse on mathematics?

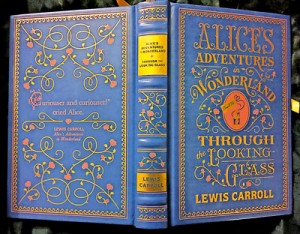

While you must be familiar with the tale of Alice who fell through the rabbit hole from the classic 1951 Disney movie, it is less likely that you have read the original versions of the story: Lewis Carroll’s 1865 and 1871 children’s books, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. Carroll’s stories, both international bestsellers have been published and translated into well over a hundred languages. Indeed, Alice’s adventures with the Mad Hatter, the talking rabbit, and Tweedledee and Tweedledum captured the minds, hearts and imaginations of children and adults alike in the late 19th century and its uniquely humorous poems and evocative descriptions are immortalised in pop culture and possess as much emotional impact and entertainment value for those living today. The stories explore themes of childhood and adulthood, and logic and reason while using creative fiction to address the changing landscape of mathematics during the period in which Carroll wrote.

While you must be familiar with the tale of Alice who fell through the rabbit hole from the classic 1951 Disney movie, it is less likely that you have read the original versions of the story: Lewis Carroll’s 1865 and 1871 children’s books, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. Carroll’s stories, both international bestsellers have been published and translated into well over a hundred languages. Indeed, Alice’s adventures with the Mad Hatter, the talking rabbit, and Tweedledee and Tweedledum captured the minds, hearts and imaginations of children and adults alike in the late 19th century and its uniquely humorous poems and evocative descriptions are immortalised in pop culture and possess as much emotional impact and entertainment value for those living today. The stories explore themes of childhood and adulthood, and logic and reason while using creative fiction to address the changing landscape of mathematics during the period in which Carroll wrote.

Both Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, written and set six years apart, evoke central themes of childhood, coming of age, maturity and thus demonstrate the necessity of reason and order in wider society. Carroll achieves this by wielding the genre of “literary nonsense” which mixes twisted logic and word play with a perennially dynamic setting imitative of the transient and fluid nature of dreams, as his iconic protagonist is unpredictablywhisked across surreal communities, sceneries and expressions. In Adventures in Wonderland, ten-year-old Alice is initially overjoyed to encounter a curious assortment of oddities, from anthropomorphic animals to talking flowers, to an animated set of cards, but ultimately tires of this impenetrable fantasy world that is impossible to decipher. “We’re all mad here,” the Cheshire Cat tells Alice. “I’m mad, you’re mad. You must be [mad] or you wouldn’t have come here.” This revelation denotes a turning point in Alice’s personal growth, in which she internalises a penchant for logic and reason in stark contrast to the inscrutable madness of Wonderland.

Furthermore, necessity for reason and order is reiterated with the pervasive theme of identity, something Alice struggles with in the early stages of the first novel, allowing herself to be continuously domineered by the creatures of Wonderland whilst being mistaken for different girls and even species. Carroll symbolises every human’s transition from fluid, imaginative childhood identity to the more stable and assured persona of adults with Alice’s literal growth and shrinkage throughout the novel, which she perilously regulates by eating an array of cakes and mushrooms, resulting in a more assured protagonist, who refuses to be ordered around by the Queen of Hearts and her court.

The protagonist’s psychological evolution is fully exemplified in the sequel Through the Looking Glass, in which a more mature teenage Alice dozes off to sleep and once again awakens in a fantasy dream-world that she ambitiously sets out to become queen of via a series of command decisions and methodical strategies, which demonstrates adult reason overriding childhood creativity.

Analogously, Carroll’s work can be conceived as a critique on Victorian era mathematics, which was deviating from standard rules and norms and rapidly becoming increasingly abstract. A little known fact is that the name Lewis Carroll was merely the pen name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson; a career mathematician who had published work on geometry, matrix algebra and mathematical logic. In the late nineteenth century, Dodgson saw a movement in his discipline that undermined conservative fundamentals based on reason in favour of freedom from representational qualities. English literature scholar Melanie Bayley proposes that elements in Adventures and Looking Glass convey Dodgson’s concern with the changing landscape of 19th century mathematics, with the absurdity of Wonderland reflecting his fears of new symbolic algebra, as opposed to conventional arithmetic. For example, Alice’s incorrect recital of multiplication tables as she falls through the rabbit hole represents this shift, as she slips out of the traditional base-ten number system to something foreign and illogical. Furthermore, Dodgson’s conservative emphasis on Euclidian Geometry is represented by Alice’s determination to control her growth and shrinkage, thus diminishing the importance of absolute magnitude in favour of resptive ratios of one length to another.

Finally, the croquet game in Adventures exemplifies Game Theory, which postulates that no agent exists independently but instead in a constant series of moves which intersect with fellow agents. During the erratic croquet game, Alice’s mallet turns into a flamingo which continuously turns in the opposite direction that she wishes to hit the ball. Meanwhile, the concept of a Zero-Sum Game, attendant on the idea that gains and losses are maintained in perpetual equilibrium, is demonstrated in a race Alice competes in against a motley crew of animals, in which everyone must run until fatigue overtakes their limbs, ultimately deeming them all winners, aptly depicting the author’s dismal perspective on new approaches to mathematics that bordered on nonsensical, expressed in an ethereal, childish, dream-like landscape.

Beneath the deceptively idyllic and senseless atmosphere of Lewis Carroll’s novels lies a comprehensive critique of the transformative landscape of Victorian era mathematics, as well as poignant portrayal of childhood on the brink of adulthood. Therefore, both Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, will – despite being traditionally marketed to children – appeal to both young and old alike, with their lush descriptions, zany sense of humour, rich symbolism and scintillating stances on human society.