The methods and the madness

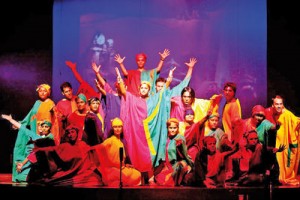

One of the Workshop Players’ landmark productions: Les Miserables. Pix by Shehal Joseph

When I met Jerome for the first time more than 25 years ago at St. Peter’s, he was already a legend. He was famous. And terrifying. The archetype of a theatre director. Full of artistic mannerisms, eccentric beyond belief and well, slightly mad. Or so it seemed at the time. To the 14-year-old me, this man was very, very strange. His pirate-like beard, perfect English, stentorian voice, ballroom dancing abilities, cat-like agility and really short shorts were all just ‘too much’. Too much to process or comprehend.

Fast forward 25 years.

The Workshop Players, which celebrates our 25th year this March, has been successful beyond our imagination. When we pulled together 33 students to a dusty classroom at St. Peter’s College in March 1992 for a series of drama workshops conducted by Jerome, we had no clue what we would eventually achieve. And now, having continuously worked with Jerome over all these years, this year’s milestone prompted me to write a personal tribute to the man who has made English theatre in this country what it is – a thriving and healthy hub of creativity and star-class entertainment. His direct and indirect influence touches almost any production that makes it on to the boards today, not just at the Lionel Wendt, but to halls and school auditoriums around the country.

But rather than write a biographical epistle about him and his invaluable and un-documentable body of work in English and Sinhala theatre, this is to give an appreciation of, and insight into his methods and ‘madness’.

This is, in my own words, how he does what he does. And why.

His methods

Keep learning. From everybody.

Perhaps the most significant thing that I have always admired in the man is his continuing quest to learn more about his art form. His teaching methods, his knowledge and even his direction itself have kept evolving. He is a seeker – a voracious reader of anything related to theatre allowing him to have something ‘new’ up his sleeve all the time.

The first to admit his lack of any formal training or education in theatre, he is eager to listen and learn from anyone, who has a skill or piece of information that adds to his existing universe. The Workshop Players have been enriched time and time again by the number of people he has invited, to share their expertise and experience to enhance what we do — directors, musicians, dancers, singers, yoga instructors, mimes and teachers who were welcomed into our midst.

Quite recently when I shared something I had randomly learnt on a recent backstage tour, I could see him committing that nugget of information to memory, and I have no doubt that it will now be part of his lexicon in the years ahead.

The Lion King: A memorable and colourful show

However, this does not imply that random cast members can challenge him at every turn! And woe betide you, if you try that when rehearsal is in full swing.

Divide, delegate and conquer

In the early years of The Workshop Players (WSP), we relied on Jerome for direction and guidance on everything. How to walk on stage, where to stand, what the singing should sound like, what the dance steps were, what the costume design should be, what the make-up should be, where to hang the lights, how to change the set, manage the money and production budget… everything. Today it’s a completely different ball game.

Productions are far more expansive and expensive and way too complex for any one person to shoulder the workload. Responsibility is divided and handed over to trusted lieutenants who will go to Jerome only when advice or approvals are needed. So much so that when he walks into a rehearsal, it is already in full swing. Without the experienced hands of the Workshop’s seniors, the committee, stage, lights and sound crews, the mammoth productions we are known for are impossible. And Jerome knows this. Which is why he spends so much time and money on building those key players. Half a dozen Workshoppers have been given opportunities to witness numerous productions overseas, to broaden their skill set, and most importantly given the freedom they need to do their jobs.

The production is not a collection of ‘scenes’

Often the Achilles Heel of an amateur production is what happens between scenes. Scene changes. At times, audiences are kept waiting for minutes listening to entire songs play out as instrumentals while the set is changed behind curtains or in darkness, in today’s context giving everyone a chance to mentally leave the show and ‘check Facebook’ or some messaging app. The magic of the theatre experience is lost.

Good productions flow smoothly from scene to scene. And that transition is planned by Jerome well in advance. How a scene is changed is directed and rehearsed almost as often as how the scene itself is played out.

One of the most dramatic scene changes we had to pull off was the transition to the Phantom’s iconic underground lair from Christine’s bedroom. In our 2002 attempt at ‘The Phantom’ this change took four minutes before the Phantom theme song was played and the scene was set. Back then, Ranga Dassanayake had to create an entirely new track just for this. When we finally produced the show in 2014, there was no ‘change-over’ time at all. The change had to be seamless and it was designed to be, and then rehearsed, repeatedly, till it was achieved.

Multiple casts and the roster

Often one of the most criticized aspects of our shows has been the multiplicity of casts, leading to many comparisons and endless questions. Which show night is better? As with many things, in our strength lies our weakness and vice versa. Our very first show back in ’92 was picked by Jerome based on the size of the cast – the number of speaking roles, purely for the purpose of giving as many of us newcomers an opportunity to tread the boards. Even that show (Lost in the Stars) featured a rotating cast.

Often at odds with Jerome on this same subject, I know for certain that this has made us a better theatre company, as one of our major strengths lies in our numbers. Moreover, this also gives lead performers an opportunity to learn from each other and thrive on a group dynamic, even in a lead role. It ensures a high degree of discipline and dedication among the cast. No one is ever allowed to ‘hold the show to ransom’. The production takes precedence, and everyone knows it.

At the same time, he has many ‘rules’ that he applies to see which combination of individuals will be cast to work together. Not all permutations and combinations are used – only those that make artistic sense. Romantic couples need to ‘look right’ together. Height and build do matter. Voices must blend. Cast the experienced performer with the novice. Individual strengths and weaknesses must combine well to give off the best to the audience.

Don’t direct everything

During one rehearsal ages ago, the final battle scene in Les Mis lacked a certain intensity, and Jerome famously yelled at all of us to “Put more life into your death!” The laughter was raucous but the point he made was clear – one that he makes over and over again to every one of his actors – you must do more with your role than simply doing what you were directed to do. Often using the phrase “I’m only giving you a skeleton”, Jerome expects the actor to add to his direction and fully ‘flesh out’ the performance by adding nuance and characterizations. When pushed to do this is when the performers truly come into their own, at times taking the rest by surprise. That energy feeds everyone in the rehearsal room, pushing the entire ensemble to excel.

The man who made it all happen: Jerome de Silva. Pic by Andre Perera

The Madness

Working with Jerome is a life full of rules. Seemingly ridiculous ones. For a first timer, these seem trivial. Stupid almost. They make no sense. Until you sit on the chair next to him.

The ‘Handing Over’ Ritual

At the end of our last dress and technical rehearsal, Jerome will de-brief the cast and crew with any last minute pieces of advice and then leave his spot at the front row of the theatre and invite the stage manager to take over. Why is this important? For a few reasons.

Any professional production is not controlled by the director. He has done his job and in most cases does not have the skill it takes to ‘run’ a show either. The stage manager is the rightful ‘boss’ and all decisions are his/hers – when to start, or even stop the show. It’s their job to keep the cast and crew in line and things ticking over smoothly. Jerome, with his little ritual, lets everyone know, that even the most senior performer or crew member is now duty bound to listen to the Stage Manager. A critical success factor for a production where you can have as many as 150 people running around in the dark and under severe pressure.

‘Opening Night’ is the night before opening night!

Everyone knows the phrase ‘The show must go on’ but rarely does anyone know what it takes to make that happen. People are taught how and where to re-set a show to in case the unthinkable ever happens. The final test is the night before opening night. The rehearsal is run exactly like a show night, and nothing will stop the run through. In the last few years Jerome, the perennial teacher, has also invited students of drama who couldn’t normally afford to watch the show, to witness the last rehearsal. Thus the desired effect is achieved for the cast and crew – an audience in house. And the show is fully tested, under show-night conditions. Professional shows the world over do exactly the same thing – previews.

Never sit in the front row

During the final rehearsals on stage, with the auditorium in darkness, no one is ever allowed to sit in the front row of the theatre. Keep those seats clear, you are told. But why?

Because to him, ‘Sight-lines’ are everything. Jerome works tirelessly to ensure that every seat in the house has a clear view to the important aspects of the show. He will position and reposition actors, props and sets till it is ‘just right’ from all angles of audience viewing, ensuring that no one is ‘masked’ by another actor or a piece of furniture.

Curtain calls are rehearsed

And you HAVE to run. Eternally striving for a more ‘professional’ look and feel of a production extends to how Jerome choreographs a curtain call. At times this is done weeks before the show commences and is rehearsed with every run-through so that it is executed in a slick, effortless fashion. Why? For one, that is what happens on stage at productions on Broadway or the West End. There is no long, drawn out, self-adulatory curtain call. And in his usual humble, gracious manner, Jerome doesn’t feature himself in a curtain call, except on opening and closing nights – allowing the cast and crew to enjoy their moment, soak up the audiences’ appreciation and gain the motivation they need for a long and tiring production run.

Everything is planned, almost everything is changed

Jerome’s preparation for any show is exhaustive. His handwritten notes on scripts and half sheets are meticulous. The performers’ directions, the set, set and costume changes and lighting guides are all planned well in advance. However, when the final show comes together on the stage, the set is built and the lights are focused – almost everything undergoes change. And that is part of his mastery. To visualize what has to be done well in advance, prepare extensively for it, but yet, to be able to adapt and change. And not just slight or cosmetic changes – drastic ones if needed. Changes that, at times, have the cast and crew in a dither trying to cope.

Do it again!

As the years passed, the man seemed to age, just a bit. We now see a much more sedate Jerome. Gone is the quick and highly flammable temper. Swear words are almost extinct. And the really short shorts are a thing of the past. However, the Task Master remains. Even if it’s 4 a.m. – do it again! There really is no substitute for hard work and rehearsal and Jerome knows it.

Working with Jerome has a rulebook of its own. Suffice to say that if you ever find yourself on stage in one of his shows, here are two last rules to help keep you safe from his wrath – Never stand in a straight line and don’t touch the side curtains. Ever.

But most importantly, have faith.

Jerome is as much a man of God as he is a man of the theatre. His faith is the bedrock on which he builds his work. Before and after shows, WSP will always gather to pray, in all the faiths we have represented on that night, which is due to his influence. Pre-production prayer has been a source of strength to every nervous amateur and hard-nosed veteran. Far too often, Jerome has risked everything and turned a production on its head to make it better. And when it works, as it does unfailingly, he is the first to testify to his source of inspiration. And at times like that, his words speak louder than those of any preacher.

The Final Act

Every time you see some English Theatre production in Colombo, you will see shades of Jerome, whether you know it or not. For one, some of the most prolific directors who produce good theatre today have all had their early careers influenced heavily by Jerome – Ruwanthie de Chickera, Jehan Aloysius, Feroze Kamardeen and Jehan Bastians all benefited from his guidance and direction early on in their careers.

Also, too many schools to count at the Inter-school Shakespeare Competition last year were directed by his ‘students’, many of whom are now fledgling theatre directors and producers themselves.

Countless productions have their lighting designed and executed by Gihan and Rohan Jayatilake, who attribute almost all of what they know of the art of theatre lighting to Jerome and working with him. The same goes for the young and upcoming mover and shaker in theatre – Javin Thomas. There are also very, very few actors treading the boards today who have not worked with or been directed by him at some point. And by conducting Junior Workshops regularly and directing shows for a number of schools today, Jerome is steadily building another generation of theatre lovers, cementing his legacy for years to come.

When finally, the time comes for the pantheon of demi-gods of Sri Lankan Arts have their names etched in marble somewhere, along with those of Lester James Peiris, Chitrasena, Lylie Godridge, Lionel Wendt and George Keyt, you will find the name of Jerome L. De Silva.

Even if I have to put it up there myself.

(Surein de S. Wijeyeratne is the Assistant Artistic Director of The Workshop Players and its Music Director)