Riveting performance by ‘Virtuosi in Concert’

Standing ovation: Gabriel Magadure, Shani Diluka and conductor Keiko Kobayashi take a bow. Pix by Srilal Ahangama

On March 15, classical music aficionados in Colombo had the privilege of seeing three world-class musicians, namely Shani Diluka (piano), Valentin Erben (cello), and Gabriel Le Magadure (violin), performing Beethoven’s Triple Concerto in C Major with the Symphony Orchestra of Sri Lanka (SOSL) at the Ladies College Hall. The concert was sponsored by the People’s Bank.

Shani Diluka (of Sri Lankan parentage) born and raised in Monaco and currently based in Paris is a busy concert pianist in Europe with several critically acclaimed discs to her name. Her husband, Gabriel Le Magadure, is a full-time member of the prestigious Ebène Quartet with a distinguished track record. Valentin Erben, co-founder of the legendary Alban Berg Quartet and one of the world’s finest cellists, lives in Vienna. Magadure plays a 300-year old Guarneri and Erben, a 1722 Goffriller – both priceless instruments.

This was the second time these three virtuoso musicians performed together as a trio in Colombo. From the dignified and harmonious manner in which they played the triple concerto, it was clear they had a profound, intuitive grasp of what Beethoven had in mind when he composed this unusual piece for piano, violin and cello. The composition (about 36 minutes long), with a genial and lyrically inclined score, is noted more for its charming melodies than its intellectual content, in contrast to the composer’s iconic violin concerto and his five monumental piano concerti which, arguably, are far more intellectually complex works. The triple concerto is predicated on limited dialogue between the orchestra and the three soloists which, perhaps, is why some experts view it not as a typical concerto but as a glorified piano trio.

The guest conductor was the dashing Keiko Kobayashi, who is held in high regard in the Far East as well as Europe. She is Permanent Conductor of the Tokyo Wind Symphony Orchestra as well as Chief Conductor of the Japan Wind Ensemble. Although the triple concerto was not by any stretch of imagination a heavyweight piece, it was a challenging one for the conductor, given that she had to maintain overall balance between the orchestra and the three soloists while at the same time directing “internal” dialogue among the latter in a way that crystallized the essence of the music. Although from time to time there are brief solo passages (piano, violin, cello) that meld into one another like a series of wavelets, the concerto is characterized by the absence of any distinct cadenzas; which, perhaps, is the composer’s way of showing that no one instrument should dominate the aural experience.

It is reported that even the legendary Herbert von Karajan was uncomfortable directing this concerto due to the uncommon blend of piano trio and orchestra squeezed into a traditional, tripartite framework. In another sense also the concerto is unconventional as the second movement (Larghetto), which is surprisingly short, serves simply as a bridge to the third movement (Rondo) – a polonaise and a bolero rolled into one with a rousing coda to conclude the work.

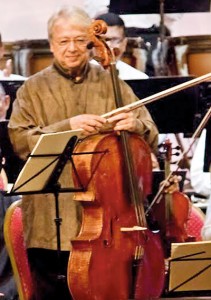

Valentin Erben

But here was Kobayashi (who was wedged between the orchestra and the grand piano and, hence, barely visible) directing this piece with such panache that it sparkled like vintage champagne. Some conductors put the musicians (as well as the audience) to sleep while others keep them on their toes. Kobayashi clearly belongs to the latter category. This was outstanding teamwork by the conductor (who, though small in stature, possessed giant leadership skills), the ensemble (which rose to the occasion with aplomb), and the three soloists (who collectively displayed exceptional clarity and fluency). No doubt, if the composer was listening, he would have enjoyed this pristine interpretation of his beloved triple concerto. The performance was as riveting as it was ennobling due to the rich moods, colours and emotional textures created by the trio with excellent support from the ensemble, which has grown in stature over the years.

The quality of sound produced by the Guarneri (violin) and the Goffriller (cello), however, was far superior to that of the Bluthner (piano). Although Bluthners, Bechsteins and Bösendorfers are more or less in the same league (just a notch below the Steinways), this particular instrument had a muted sound. (Perhaps it is in need of an overhaul.) But the tonal mismatch between piano and solo strings was barely noticeable because Shani Diluka was the pianist. If Diluka possesses a unique gift, it is her uncanny ability to extract magical sounds from any piano she plays.

The triple concerto was preceded by the Overture, “The Barber of Seville” (Rossini) and “The Inn of the Sixth Happiness” (Arnold), in that order. The Overture, recycled from two previous Rossini operas, is noted for its brisk and lively Neapolitan dance climaxing in a glorious crescendo – Rossini’s trademark. Even though the SOSL is a medium-sized ensemble, it produced a rich, full-bodied sound that did justice to the crescendo. Kobayashi’s bouncy style of directing was ideally suited to this piece which ends with an enthralling coda, neatly executed by the ensemble.

The award-winning British composer, Sir Matthew Arnold, wrote several film scores, including “The Bridge on the River Kwai” and “The Inn of the Sixth Happiness.” The orchestral suite (consisting of excerpts from the latter) could be described as semi-classical – a lovely percussive piece that includes an expansive “determination theme,” an eloquent tone poem, and a delightful quote from the children’s perennial song, “This Old Man,” embedded in brass. Thanks to some powerful chemistry between the conductor and the orchestra, the magic of this suite was captured in its entirety.

The encore was the icing on the cake: Mendelssohn’s Piano Trio No. 1, slow movement – performed with such grace and sensitivity that the audience gave the trio a standing ovation.