News

In this Kataragama village, abject poverty drives children to begging

Sooriyaarachchige Sarath lives with his family in Gothamigama, one of the poorest villages in the area. Pix by Indika Handuwala

Y.A. Sanjeewa dropped out of school at Grade five. He says his parents were too poor to keep him in school beyond that and it was more important that he went out and earned some money to help the family. He is 30 now, married with two children. His is keen to educate his children at least up to GCE ordinary level in school. But living in abject poverty in the village of Nagahaweediya in Kataragama, he is unsure whether he could do that.

“I face the same problems that my parents faced. Without money, it is difficult to get an education,” Sanjeewa said. His income depends on the manual labour work that he gets from time to time but has no regular income.

His story is symptomatic of a wider problem faced by many living on the fringe of one of the most visited scared cities in the country — Kataragama. While thousands of people from all over the country flock there each year, what many people do not notice is the hardship that these poverty-stricken villagers undergo.

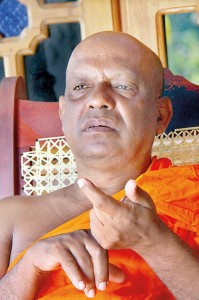

The Ven. Kapugama Saranatissa Thera, Chief Incumbent of the Sri Abhinawarama Viharaya, has been living with these people for the past 50 years, offering counselling and guidance. Having been ordained at the age of 11, the Thera has also served as Principal of President’s College, Kataragama .

“Kataragama is a highly commercialised town and children find it easy to earn money at a young age due to the large number of pilgrims who come here. Parents who are not educated would prefer to use their children for begging to make some extra money than send them to school,” the Thera said.

While most children of schoolgoing age have enrolled in the nearest school in the area, attendance is poor with some coming to classes once a month or even less regularly. “Once children get used to handling money at a young age, it’s difficult to wean them away from it and get them interested in going to school,” the Thera explained.

Ven. Kapugama Saranatissa Thera

He recalled an incident where a child was injured due to a fall and had to be admitted to the Kataragama Hospital. The incident had taken place on a Friday and early next morning the boy’s father had come to the hospital and insisted that his son be discharged. The hospital had refused to release the child as he had suffered a concussion. the man had then argued with the doctor in charge and insisted that his son be discharged immediately. When asked why he was so adamant to have the child who was still recovering discharged, the man confessed that since a large number of pilgrims visit the scared city on Saturday, he wanted to use his son as a bait to beg.

While children are deprived of schooling in this way, their parents too have few opportunities to make a living. Most people depend on handouts from pilgrims, temples and charitable organisations in the area.

“One major reason that people here are unable to overcome the “dependency syndrome’ with which they have lived for years is the lack of employment avenues. Even small scale industries have not been set up in the area though there is scope for manufacturing of goods that are in demand among the pilgrims,” the Thera said. Besides, the Thera said there are few opportunities for vocational training for young people so that they can find jobs elsewhere.

Sooriyaarachchige Sarath lives with his family in Gothamigama, one of the poorest villages in the area. He grows medicinal plants inside the thick jungle area and treats villagers for minor ailments. He too dropped out of school at a young age but learned herbal medicine from his father, an Ayurveda practitioner.

Sarath is eager that his 14-year-old son completes his school education. “He is a good student and I would like him to continue his education,” Sarath said. He too is worried that poverty would derail his hopes for a better education for his children.

Poverty, lack of education and unemployment often result in people falling into trouble with the law. It’s a vicious circle, say Kataragama’s Chief Inspector Upali Kariyawasam.

Other than ensuing that children are sent to school and not for begging, the Police also often have to deal with cases of statutory rape, illegal poachers and touts who harass pilgrims.

“It’s very difficult to keep children in school up to grade ten in this area. Many of them drop out at around 15 years of age,” Mr. Kariyawasam, who is the Officer-in-Charge of the Kataragama station said.

This in turn has given rise to other social problems such as teenage pregnancies.

“We have on record several cases of teenage pregnancies. Some of these girls were not even 15. These things come to light only if they are admitted to the hospital and the doctors report to us saying they suspect the girls are under age. But there are many cases that go unreported,” he said.

Chief Inspector Kariawasam

Chief Inspector Kariyawasam said the Police had adopted a holistic approach to deal with such problems by advising both parents and their children in such instances. “There was a 15-year-old girl who was admitted to hospital recently. She was three months pregnant. She was living with a young man of 22 and it was an arrangement that had blessings of the girl’s parents,” he said.

“Unfortunately many parents also see a teenage daughter as a burden and are happy if they find a partner and leave the house. It is one mouth less for them to feed,” he said.

Several programmes carried out by the Women’s and Children’s Bureau of the Kataragama Branch of the Police, through various organisations, to educate adults on the mandatory requirement to send children to school up to 14 years of age and other related issues have yielded limited results but changing attitudes is proving difficult.

As the Ven Saranatissa Thera said there must be the will on the part of people to help themselves and there should be a more concerted effort from government authorities to free these unfortunate people from their poverty-stricken existence.

Y. A. Sanjeewa depends on the manual labour work that he gets from time to time but has no regular income