Columns

THE SUNDAY PUNCH VESAK TRILOGY: The Birth, the Enlightenment and Nirvana of Gautama the Buddha

View(s):Morning had broken. The dawn the world and the heavens had for epochs waited to break upon the land, had finally come to pass.

And on that Vesak full moon day 2640 years ago, in the year 623BC, the rising sun sheds its tender early morn light to reveal the scene of a royal litter emerging from the gates of Kapilavasthu, the capital of the Shakyas, in northern India.

At the centre of this royal convoy, borne upon a golden palanquin, sits the queen of the domain. She is accompanied by her sister and a host of royal attendants. With the blessings of her husband the king, she is leaving the gates of his kingdom, embarked upon a journey to her parents’ palace in Devadaha. Heavy with child, Queen Mahamaya is going home for her confinement to bear a son to her husband King Suddhodana and provide an heir to his royal throne.

At the centre of this royal convoy, borne upon a golden palanquin, sits the queen of the domain. She is accompanied by her sister and a host of royal attendants. With the blessings of her husband the king, she is leaving the gates of his kingdom, embarked upon a journey to her parents’ palace in Devadaha. Heavy with child, Queen Mahamaya is going home for her confinement to bear a son to her husband King Suddhodana and provide an heir to his royal throne.

As the royal litter progresses upon its charted path at a sedate pace so as not to jolt the expectant mother and cause any untoward happening, the Queen reflects on the extraordinary events that had occurred in the months recently past. The failure to bear a child for many years had been the subject of vicious social comments and snide court gossip. Her barrenness was taken as an omen to the terrible fate that awaited the royal kingdom and, though none dared to express it in her presence, she knew they privately ostracized her for it. Perhaps even the king, though so kind, gentle and loving, bore some ill will, secretly and unconsciously deep in his heart; and it had caused her pain to think that she was the source of his unspoken grief over her inability to conceive. And then, just when she had resigned herself to a life of sorrow, there came the dream.

Ah, yes, how vividly she remembered that dream — the dream she had had nearly a year ago. She had dreamt that she had been carried forth by the four world deities to the tableland of the Himalayas. There the wives of the four world guardians had welcomed her and taken her to the Lake Mansarovar. In its cool, clear and refreshing waters they had bathed her and then dressed her in a robe of exquisite beauty and decked her with gold ornaments and garlanded her with sweet smelling flowers of divine scent.

Then, through the distant hazy mist that engulfed the plateau, she saw approaching her, a white silvery elephant of magnificent appearance, which walked with measured steps and noble bearing. It circled her thrice; and then, with a salutation with its raised trunk, entered her soul. When she awoke, she had related the dream to the king who immediately summoned the royal astrologers to interpret its import. They prophesied that the queen was destined to give birth to a son who will do his father proud. “He will be,” they proclaimed, “A ruler not only of this province but of the world. An emperor whose empire will be forever.”

Even as she recalled those words now, Mahamaya experiences a sudden surge of tears break out from her eyes and cascade down her cheeks, the same surge of joyous emotion she had felt that day hearing the astrologers proclaim the greatness her son was destined to achieve. As she brushes her tears away with her hand, she also recalls how she had asked them, not in disdain but whimsically, “but will not death steal the spoils of any empire?” and how, and with what confidence, they had replied, “Nay, while death will indeed rob the accumulation of wealth and power, it is impotent in the face of the eternal. Your son, may not rule with arms which is but fleeting but conquer, with his philosophical doctrine, the souls of all mankind which is eternal.”

THE BIRTH: In the shade of a sprawling sal tree at Lumbini Park, Queen Mahamaya gives birth to Siddhartha 2640 years ago

The queen cannot but help let a smile light her face, as she remembers how the king had not been amused to hear this part of the sages’ prophecy. The king would have none of that. Not for his son to become another wondering fakir babbling stanzas from the Upanishads when he had a kingdom to overlord, administer and to defend as any noble Kshatriyan, the warrior caste, was duty bound to do.

The king had flared. “Religion is for the Brahmins,” he had declared with scorn. “Let them use the monopoly they enjoy having sole access to God. But no son of mine is going to be a hermit, a beggar, parroting lines from the Rig Vedas in return for a measly bowl of alms. My soon to be born son is a Kshatriyan, a warrior born of noble blood, born to be king, born to rule in the self-same manner of his ancestors. In the manner his caste dictates and Kshatriyan honour demands. I will see that my son will follow in the path of his ancestors”; and – little knowing that the path of the Prince’s ancestors lay in the way where twenty seven others had trod eons before – had contemptuously dismissed his royal astrologers from his presence.

Absorbed in the recollection of those happy moments that had followed her dream and the confirmation that soon came that she was pregnant with child – confirmation that she was not condemned to a life of barrenness but was fertile to bear the king a son and heir – Queen Mahamaya proceeds on her journey to Devadaha to her parents’ palace to give birth to the royal child. Out of a sudden whim, she draws the curtains in her palanquin aside and glances out to take in the passing scene and fresh air. What beholds her eye moves her. The royal litter is passing the beautiful tranquil Lumbini Park.

The park’s serenity and its natural beauty which appears akin to the divine grove of Cittalatha, stirs in the queen a strong desire to break journey and to pause there for rest: and she orders the litter to stop and alights from her palanquin. She strolls with her sister and attendants the broad acres of the lush and verdant park; and comes across a sprawling sal tree, where she reclines under its placid soothing shade. A gentle breeze flutters, the leaves rustle and she suddenly sees a branch of the sal tree swoop to the earth until it almost touches the ground.

Drawn by some inexplicable, invisible force, she grasps the bough and is lifted by its upward return and the sudden movement causes her to experience the first pangs of imminent labour. With curtains hastily drawn around her, with one hand clutching the sal bough in direct touch with nature, the other clasping her loving sister Prajapathi’s hand, within cloistered cool and selected privacy, she gives birth to her son.

Thus was the Prince born. Amidst the windblown flow of nature. Amidst the song of birds, amidst the sounds of nature. Amidst the scene of beauty, flushed with greenery. A prince of noble royal blood, born not in the ornate and artificial confines of stately palaces but by the wayside, beneath the leafy shade of a sprawling sal tree, born in nature, alike nature’s beings on earth.

Whether Siddhartha, having drawn his first breath in the unspoiled open air and having witnessed his first view of the world in nature’s unsullied splendour, instinctively possessed a strong affinity with nature for life, none can tell or ever know. But considering that all the important events in his life occurred in the open air, perhaps it can safely be said, that his birth on that full moon day in the month of Vesak in that shady sal grove, firmly bonded him to live his life in nature’s arms and to be allured by her irresistible devotional charms.

The royal litter turns round and heads home with a royal addition in the queen’s palanquin. News of his arrival on earth had already preceded the arrival of the new born prince at the Kapilavasthu kingdom gates and he is welcomed with pageantry and mass affection by the multitude. They see in him their future king, their saviour, the blossom of their future hopes and promise, the defender of their faith and the guardian of their wellbeing. Destiny had delivered their prince to their doorstep; and, in that infant bundle of joy, they see reposed the future custodian of their calm and comfort.

No sooner is the prince safely ensconced in his bassinet, an old and revered sage comes to see the new born. From the 32 auspicious marks on the infant’s body, he discerns the signs of greatness and predicts, “He will gain an insight to the cause of universal woe and will marshal the minds of mankind and lead them to seek liberation from the siege of sorrow. Today we have no answer, no way out from sorrow’s web that has entrapped us all. He will show the way out; and for epochs to come, as long as his teachings exist, man will not stand forlorn. “

But, in the midst of great rejoicing in the city over the Prince’s birth, there comes death which strikes at the very heart of the royal palace.

Four days after his birth, the great naming ceremony takes place; and the Prince is named Siddhartha, the All Knowing One. But then, in the midst of gaiety, the royal household is plunged in despair as Queen Mahamaya suddenly takes ill. And as her condition worsens, the king and the queen’s sister keep vigil at her bedside, absorbed in prayer.

How could it be, they asks themselves, that after such a seemingly painless delivery, that she should succumb to the scythe of sickness? How could the full force of untrammeled joy be trampled in the dust in so short a time and turn to naught the unbridled bliss of the royal household? Was this the meaning of the world, the meaning of life, the humour of the Gods whose blessings were but fleeting, who gave in jest only to cruelly snatch it away?

And was the Prince the cause? Was he, the bringer of life and hope to the Palace, also the harbinger of death and doom? The exuberance, with which his arrival was greeted, only five days before, is now replaced with despondency and gloom. And the unspoken word lingers and spreads from the palace walls, beyond the moat, onto the streets and into alleys, filling every nook and cranny of the land. Is he the cause? Is he the curse? Had the euphoria his arrival had ignited, cast an evil eye on the royal household? Had his birth lifted the veil of gloom only to bring the curtains crashing down in mourning? Would sorrow be forever branded on his brow? Would he, for the rest of his life, carry with him the bowl of woe as his trademark and taint the world with sorrow’s stain? Was he bad news?

There were no answers they could find to explain the sudden sad turn of events and the tragedy unfolding before them. The queen’s condition deteriorates rapidly and she realises the end is drawing near. On her death bed she turns to her sister and implores her to be the mother she can now never be to her infant son. She says: My dear sister, I entrust my son to your care, to nurse him, to protect him, to love and bring him up in the same manner of a mother, so that, though I will not be there to tend, he will not be left bereft of a mother’s love. Bring him up as your own. Promise me he will not feel even by an iota the absence of a mother’s arms and love.”

Then, with tears in her eyes, she turns to her sire, the King and asks his forgiveness. She says, “If I failed you, I failed only once and it is now for I perforce must leave you helpless with a new born son without a mother to care for him and I beg you to forgive my unalterable fate. Now the time has arrived and I must take your leave for I can hear the gods calling me to return and I can see a host of angels waiting with their silver chariots to bear me back from whence I came from. Farewell, my love, and may the Gods bless you.”

Seven days after Siddhartha was born, the shadow of sorrow falls upon his cradle; and he lays there in the dark, a motherless child.

Days before the city had been enraptured with joy celebrating the birth of a son and heir to their king. Now it is engulfed in sorrow, mourning the sudden demise of their beloved queen. And though they question the unfairness of it all and curse the fickleness of fate, neither the king nor any seer nor anyone else in the world can find answer or understand the vicissitudes of life and what lies at its core and knows not the way out from sorrow’s fort.

It wasn’t surprising that they could not fathom the cause of their grief nor know of the solution. Throughout the long history of the world, there had been at various times Buddhas born on earth to show mankind release from suffering. But even as they had preached the impermanence of all things, their teachings, too, had vanished in the course of time and in the year 623BC, the world lay barren of their philosophies and man wandered naked in ignorance, wondering why his life seemed so accursed.

Now the time had come for another Buddha – the 28th – to be born, not to redeem mankind for Buddhas are not saviours but only teachers – Tathagatas who only show the way. Attendant with happiness and yet flanked by sorrow, Siddhartha had been born on earth to fill the void.

But the seed was sown to set man free in countless births before: When as a shipwrecked soul on stormy sea, he bore his mother to shore. And listening to her grasping breath, choked with passion, salvaged from death, heard then her voice implore: Merit thou earned surpasses none: May thou be a Buddha, my son.

Five hundred fifty births distilled that will within his core; to realise truth and see fulfilled a mother’s wish on shore; and though his soul changed birth by birth, steadfast remained his role on earth to find the core of woe: To transcend karma’s iron clasp and free mankind from sorrow’s grasp.

Merit earned in earlier births, the riches he did gain; now stood poised to blossom on earth, to cleanse the karmic stain; His flesh, his life, his blood, his eyes had he, in selfless sacrifice, bestowed to those in pain to rendezvous with destiny, and end sojourns through eternity.

And on that Vesak full moon morn 2640 years ago, not only the world but the heavens too resounded with delight. For a Buddha born on earth they knew would heaven and earth enlight. For men and gods are both subject to fates that deal without respect woe to the meek and might: To rid the seed of incessant death, all exulted Siddhartha’s advent.

| For epochs to come, none will stand forlorn; This comes to pass when a Buddha is born THE BIRTH OF SIDDHARTHA Today the Sunday Punch presents the Vesak Trilogy: The Birth, the Enlightenment and the Great Passing Away of Gautama the Buddha. The second part of the trilogy, ‘Night Siddhartha became Buddha’ and the third part ‘The Night Buddha Attained Nirvana’ appeared on May 3rd 2015 and last year on May 22nd 2016 respectively in the Sunday Punch. This year even as Lanka begins to commemorate the thrice blessed day of Vesak which falls this Wednesday, the Sunday Punch presents the final installment: the first part of the trilogy, the Birth of Siddhartha; and the many events – both of happiness and sorrow – surrounding his advent. | |

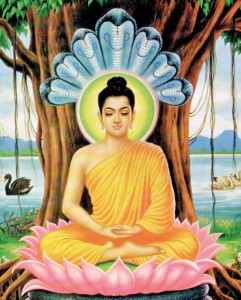

| Night Siddhartha became Buddha Over two thousand five hundred years ago in the far off plains of Northern India, a royal prince of the realm renounces his worldly life and embarks upon an unknown path in an unknown quest to find an unknown treasure that would reveal why all life dances on a razor blade, why all life weep, why all life decay and why all life die. He knows the answer lies not in ornate halls, in coffers within guarded walls or hidden in the humblest hamlets or submerged in poverty’s sewers.  THE ENLIGHTENMENT: On a full moon night in the month of Vesakha, Siddhartha, finally shedding the world’s ignorance, attains supreme bliss as Buddha Sorrow shadows the rich, the poor, the young, the old, the healthy and the sick alike and all beings born are subject to this iron law from which no perceivable end, no way out appears to exist. But he knows there must be, there has to be the path to deliverance; and he determines to find it. And he knows it lies in the way of the abode less ascetic. His search for the truth, free from the clangs of domestic chains, free from the trappings of power, free from frivolous mundane pains and free for the soul to flower takes six long arduous years which brings him to the brink of death when he realises that extreme penance like extreme pleasure will not enable him to transcend karma’s iron clasp and free mankind from sorrow’s grasp and that the path lay in the middle way. It is a full moon day in the month of Vaisakha. It is his thirty fifth birthday. Soon the evening gives way to night. He is seated under the sacred tree of wisdom, the Peepal tree under which he had sat all day determined never to rise until he had gained the ultimate. As moonlit beams stream through leaves to shed a warm glow, a breeze blows and brings a drizzle of flowers from surrounding trees. And then a gentle rain softly falls. He notices it and wonders why it is not falling on him. He looks over his head and sees the hood of a giant cobra shielding him from the rain, protecting him from the elements. The lotus is about to blossom and he sits poised in meditation on the threshold of discovery. The hours pass but for Siddhartha time stands still. He is absorbed with his surroundings With every breath he takes he takes in the subtle rustle of the wind, the soothing ripple of the stream, the sweet smell of the earth until nature becomes one with him. He enters the First Watch. From the depths of his consciousness he feels a deep stirring. The demons within him rise. They appear incarnate before his eyes, the living creatures of life’s torments. And then the storm breaks. The assault begins in earnest. From all sides the demons strike but his aura exudes a powerful shield. Then Mara, the God of the Underworld makes his entrance in a chariot drawn by his ghouls. In sonorous voice he warns Siddhartha, “Turn back. None can threaten my kingdom built on man’s insatiable greed.” Mara unleashes his forces. The demons multiply and attack but fail to penetrate the armour of his concentration. Finally Mara retreats. And Siddhartha realises Mara was his own creation; the overlord of his consciousness. He enters the Second watch. With Mara defeated his consort Maya rises to challenge Siddhartha. Maya of a thousand dances, Maya the great deceiver, Maya, the bewitching seductress. She takes up the gauntlet. This is her forte. She sends in the dancing girls. Mara’s demons now transform into beautiful damsels, their pouting breasts tightly clasped, the full round hips swirl in motion as they advance to break his concentration. He sees them taking shape, becoming more and more beautiful as they near. The music of the past rings in his ears. He feels their hands caressing his body, enticing him with their seductive allures but they fail to move him. His mind remains unshaken. He defeats Maya and her girls. He now enters the state of Samadhi. He enters into another dimension. The dimension of space. Time and space converge; the past, present and future merge into a single entity. And he sees his past births flashing before his eyes. He enters the second state and sees how all life repeats the cycle of rebirth. Born only to perish and in death to be reborn again. He enters the third state. And he dwells on the obstacles that prevent man from realising the way out of this cycle of woe. The five hindrances namely lust, anger, languor, restlessness and doubt that springs from a lack of understanding of the nature of the world. And he dwells on seven factors to realise clear vision: mindfulness, true inquiry, energy, relaxation, concentration, equanimity and joy to transcend the melancholy and gloom of the mind. Then with joy he enters the fourth state: Higher consciousness. He begins to meditate on the law of cause and effect and realises that whatever being or thing, if it has within the nature of arising, it also has within its own seed, the nature of its own cessation. The answer lay not in an external power but within the core of oneself. Absorbed thus in the nature of things his body starts to emit colours. Blue from his mind, yellow from his flesh, red from his blood and orange from his nerves and bones. There he sits under the Bodhi, rapt in meditation, in serene calmness, radiating from within a whole spectrum of colours with a giant cobra standing guard. Mara he had defeated. Maya he had vanquished but enlightenment still eludes him. One more barrier remains, the greatest obstacle of all had to be overcome. And then there dawns perception. The final chain he has to shed is his own ignorance, his own ego. It is ignorance that lay at the core of all suffering. Ignorance, the root of all ills. As the heavens resound with delight, as the Gods bow in reverence, and as the earth wraps in enchantment, Siddhartha attains the supreme state of tranquility; the quintessence of bliss. He gains Enlightenment. And as twenty seven others have done before him, he becomes a Buddha. Night the Buddha attained Nirvana: The last days of a long samsaric journey  THE GREAT PASSING AWAY: In Kusinara the Buddha bids the world farewell forever, never to return and enters into the supreme state of Nirvana And as his disciples peered into the gloom of the dying light on that full moon night of Vesak, they could scare forbear to brood in dread what luminosity now lay left to illumine the gathering dark in a world bereft of a Buddha. They had known it was coming three months earlier when the Buddha had chosen to announce it publicly at Capala Ceitya near Vesali, though the Enlightened One had known of its approach much earlier. With his two chief disciples Venerable Sariputta and Moggalana predeceasing him as had his son Venerable Rahula and wife Yasodhara, the Buddha, now in his eightieth year, had described himself as ‘a worn out cart.’ It was time, he decided, to leave Rajagaha where he was then residing; and embark on his last journey restating what he had preached for forty five years. The final destination was not to be the great cities of Savatthi or Benares but the little known hamlet of Kusinara. The journey is long and arduous. Travelling with his closest disciple the Venerable Ananda, it takes him through Ambalattikka and Nalanda to Pataligama. From there he proceeds to Kotigama and then to Nanda. He passes from village to village, from town to town sojourning briefly at each place to expound the essence of his Dhamma to the communities of Bhikkhus; and reaches Vesali where he retires with his retinue to the Mango Grove of Ambapali, the beautiful courtesan. Knowing Ambapali to be a potential Arahant, he preaches the Dhamma and edifies her on the path to enlightenment. It’s the onset of the rainy season; and the Buddha decides to spend his retreat – his forty fifth and last – in the village of Beluva in Vesali. He tells his closest disciple, ‘Come, Ananda, let us proceed to Beluva,” and they proceed thither. But with the rains, come the pains. It comes in sharp, short shocks, pointed arrows from the illness which has taken hold. Tormented by these relentless pangs of deadly pains, and with his body wracked by the severe disease and made weak, he realises the end is fast approaching. But there is still some work of noble note to be done before he can bid final farewell. It will not be fitting if he came to his final passing away without addressing his disciples and clearing the last vestiges of doubt they may have. And so he resolves to suppress his illness by his superhuman strength of will and resolves to maintain his life course and live on. Thus is the illness flayed and he makes an astounding recovery. Then the Blessed One takes his bowl and proceeds to Vesali for his alms. On his return, he tells Ananda, “Come Ananda, take a mat and let us spend the day at the Capala Ceitya.” They reach the shrine of Capala and sit down. And then the Buddha tells Ananda, “Whosoever, Ananda, has brought to perfection the four constituents of psychic power could, if he so desired, remain throughout a world-period or until the end of it. The Tathagata, Ananda, has done so. Therefore the Tathagata could, if he so desired, remain throughout a world-period or until the end of it.” But Ananda’s mind is dominated at that moment by Mara. He does not beseech the Buddha to remain for the lasting good of the world, but remains silent. The message is lost on him. The Buddha repeats it for the second time. But Ananda remains silent. The repeats it for the third and final time but still Ananda stays silent. The significance of the moment eludes him. The opportunity to invite the Buddha to remain on earth for an eon for the lasting good of all mankind flies. Then once Ananda had gone, Mara approaches the Buddha. He says, “The time has come for the Parinibbana of the Lord.” But the Buddha answers, “Do not trouble yourself. Three months hence the Tathagata will utterly pass away.” Thus here at Capala Ceitya the Buddha renounces his will to live. When Ananda returns, the Buddha tells him of his decision. Ananda recalls what the Buddha had told him earlier and realises his folly of having remained silent. He now beseeches the Buddha to remain, but the Buddha cuts him short and says, “ Enough, Ananda, do not entreat the Tathagata, for the time is past, For if you had done so earlier, Ananda, twice the Tathagata might have declined, but the third time he would have consented.”. Thereafter he asks Ananda to summon all the Bhikkhus in the surrounding area of Vesali and, after impressing upon them the truths he had preached, namely, the four foundations of mindfulness, the four right efforts, the four constituents of psychic power, the five faculties, the five powers, the seven factors of enlightenment, and the Noble Eightfold Path, he publicly announces that three months hence the Tathagata will utterly pass away.” He then leaves Vesali and proceeds on his journey to Kusinara, passing through Bhandagama, Hatthigama, Ambagama, Jambugama and Bhoganagara giving counsel to the Bhikkhus at every place until he reaches Pava. Here he is served his last meal and then falls violently ill with dysentery. The pains come and, though extremely weak and severely ill, he determines to walk the final lap of his journey to Kusinara, six miles away. Owing to his illness the Buddha is compelled to sit and rest in 25 places. At one such spot, a traveller sees the serenity of the Buddha and, so moved by the sight, gifts the Buddha a golden robe. As Ananda adorns the Buddha with it, the dazzling robe of burnished gold loses its splendor for the Buddha’ complexion becomes exceedingly radiant. Noticing Ananda’s astonishment at this transformation, the Buddha tells him: “Ananda, on two occasions the Tathagata’s skin becomes clear and extremely radiant. One is on the night the Tathagata attains Buddhahood. The other is on the night the Tathagata passes away and attains Nirvana”. He then pronounces he would pass away on the third watch of the night on that day. The Buddha arrives in Kusinara and heads to the Sala Grove of the Mallas. There between twin Sala trees he lies down on the couch Ananda has prepared for him. He lies on his right side with his head to the north, with one leg resting on the other. Though in pain, he remains with perfect composure, mindful and self possessed. Soon the Gods descend on the Sal Grove to express their grief, so great in number that not a spot is there that could be pricked with the tip of a hair that is not filled with powerful deities, lamenting “‘too soon has the Blessed One come to his Parinibbana, too soon will the Eye of the World vanish from sight”. He then proceeds to explain to Ananda variant salient points of the Dhamma, then addresses the Bhikkhus and asks them to question him as to any doubts they may have on the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha. But all remain silent harbouring no doubt or perplexity. He makes his final exhortation that if anyone thinks they have no master any longer and wonder who their master shall be, they should not ponder over such thoughts. He says: “The Dhamma and the Discipline which I have proclaimed and made known shall be your Master, when I am gone.” Then the Tathagata states his last words: “All compounded things are subject to change and decay. Strive on with diligence,” and enters the first ecstasy. Then rising from the first, he enters the second ecstasy, then the third and fourth. Rising from the fourth ecstasy, he enters the sphere of infinite space, then infinite consciousness then nothingness, the sphere of neither perception nor non-perception. Then rising from that sphere, he attains the cessation of perception and feeling. Seeing this, Ananda believes the Buddha had passed away and begins to grieve but is told by the Venerable Anuruddha, that the Buddha has entered the state of cessation of perception and feeling and that he has not passed away. Then the Buddha rises from the state of cessation of perception and feeling and enters the sphere of neither perception nor non-perception, then, in reverse order, enters nothingness, then infinite consciousness, infinite space, then the fourth ecstasy, the third, the second and then the first. The he rises from the first ecstasy, the second, the third and then the fourth. And finally rising from the fourth ecstasy, the Buddha immediately passes away in the third watch of the night; and attains that indescribable state of permanent bliss, the supreme state of Nirvana. |

Leave a Reply

Post Comment