Whetting the appetite for Singapore’s heritage food

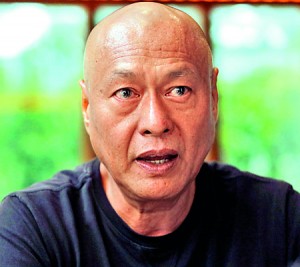

Damian D’Silva

Years of stirring the sticky-sweet, thick mixture fordodol has taken its toll on Chef Damian D’Silva’s shoulders. His joints have borne the brunt of hours of heavy mixing and are now beyond repair, he explains matter-of-factly. For the aeronautical engineer-turned-chef, hard work in the kitchen is a prerequisite for mastering cooking and his passion for his food is evident in everything he does.

The Singaporean chef, who was in Colombo recently courtesy the Colombo Supper Club, and Jetwing Colombo 7 (where he presented a tasting menu transformed into a Singapore sharing plate ‘immigrant style’) is well-known in Singapore for championing Singaporean heritage cuisine and has gained a firm following for his brand of food. For Damian, food is about good technique, fresh ingredients but more importantly, heart and soul. Last week, he sat down with the Sunday Times and discussed his beginnings with food, must-eats in Singapore and Singapore’s food culture.

* Tell us about your initiation into food as a child

I started cooking at a very young age. From my mother’s side, I had Peranakan influence and on my father’s side, Eurasian influence – so basically Portugese and Chinese. A lot of work was done in the kitchen. As children, we helped because there was always a reward at the end– food. It wasn’t just me, it was also my sister, mum, granddad in the kitchen and occasionally my aunties. It would get hectic towards the end of the year and Christmas prep was done three months before because it wasn’t just savouries – we had 6 – 7 pickles to make. We’d have green chillies stuffed with dried papaya which took a tremendous amount of time to complete. You’d have to grind the papaya, squeeze the juice, leave it in the sun and remove it and continue doing it till all the water was out.

You learn the importance of doing things methodically. You understood in the end why things were supposed to be done in a certain way. It helped me more than anything else to understand my culture, appreciate it and embrace it.

My granddad was very special because he didn’t only cook Eurasian food, he cooked Chinese, Malay, and he cooked a little bit of Indian too. When you grow up, having two amazing chefs (my grandfather and grandmother) you can learn from you tend to become, in a certain way, a perfectionist.

* Singapore is a small country with a big appetite. How did food become such an integral part of its culture?

There’s nothing for us to do – no really, think about it. We can’t go to the zoo every day. There really isn’t much of a beach and the seaside – most of it, is reclaimed. The city is full of tall, wonderful buildings. So what do we do? We eat. We go to new places. There are hundreds of new places which open every year. And of course, if you go to one you would want to experience a different one tomorrow. You’re spoiled for choice.

*There’s a vibrant hawker street food culture in Singapore and you’ve done an excellent job bridging this world of street food with restaurant dining at your food outlets. This is interesting.

Simple. You can’t eat the 200-300 dollar meal every day but you can eat the 4 dollar meals every day.

I think it’s the sustainability. You can go eat hawker food — it’s reasonable, it’s decent and it provides for you across the board. You can eat Chinese, Malay, Indian and for five dollars you can fill yourself up. The variety is quite amazing

* Is this what you’ve been trying to do with your food ventures – bridge these two worlds together and find a middle ground?

Yes and no. What I do is Singapore heritage food and I think I’m the only person in Singapore who does that. I tell people that hawker food and Singapore heritage food are different. They’re different because heritage food started 400 years ago and it changed over the years to what it is today and it consists of Chinese, Malay, Indian, Peranakan cuisine.

Hawker food was developed to feed the office worker, because it was cheap. When they went home they ate the food they grew up with, which is the heritage food. What happened was that everything changed – people didn’t have the time and the economy changed. People headed out more often than they cooked at home. A lot of the dishes cooked a 100 – 200 years back were forgotten. It was so easy to go to the hawker centre than to cook.

Singaporeans don’t know about some of the dishes I cook. Even the ones of Peranakan ethnicity have never heard of it. It’s scary because in another 15 – 20 years it could all disappear. And that is what I don’t want to happen.

* Are there any interesting stories about Singaporean heritage dishes or ingredients which come to mind?

We have a nut called keluak (Pangiumedule). This is a nut which originated from South America, and came to this part of the world with rubber trees. When the Dutch colonised Indonesia, the Indonesians would use this and put it into a soup for the Dutch. The Dutch, not knowing that there was arsenic, consumed it and it actually killed quite a few thousands. Eventually the Dutch realised it was this fruit they were eating.

We still cook this fruit but we soak it in ash to remove the arsenic. It’s called the truffle of the East. Why? Because it’s got a very unique aroma, a special taste and is what I would say, an acquired taste and is only cooked in Indonesian, Peranakan, Eurasian cuisine. It has a very strong pungent, earthy, bitter taste. But when you cook it and eat it with a sambal, it has this amazing flavour – it’s got sweetness, bitterness, saltiness and it’s got this umami that not many nuts have. You don’t need a lot of it and when you mix it with rice, it’s a dish on its own.

* What, in your opinion, are must-try dishes in Singapore?

The dishes with the nut that I mentioned – in Singapore there are quite a few Peranakan restaurants that serve it. Another dish that is a must-try is fried noodles — Char-kway-teow. It’s got a lot of lard in it (and I love my lard) and it’s got cockles, Chinese sausage and prawns. What I like about it is the textures and flavours it has.

The entire dish is fried on the wok, then you smell the sausages then you smell the garlic which is fried, then the prawns and the lard. When you put it into your mouth, there’s an explosion of flavours and textures. The bean sprouts are very crunchy and the lard is very crispy. The cockles are not cooked a 100% and are thrown in the last minute.

* What is your ultimate comfort food?

I am a very simple person – I like noodles. Any kind of noodles. And I love string hoppers (we call it putumayam).

* You came into professional cooking, late in your career. What prompted this shift?

I was tired of engineering. It wasn’t giving me the happiness that I wanted. And I also felt that what I was doing [cooking heritage food] was dying. And I felt if I could somehow uplift it, if I could teach people, I felt I could continue this legacy which I thought was so important.