Coming to Ceylon, their new home

Dental technician Yee Shiou Sen. Pix by Indika Handuwala

Tightly-wedged amongtextile-dealers andjewellers along bustling Greens Road in Negombo, is a unique shop doubling up for two trades.

Styletex claims the big board in English, while ‘Dath bandina sthanaya’ states the second line in bold Sinhala letters.

Textiles and dentures symbolize the quiet and unsung contribution of the early Chinese settlers who wandered into then Ceylon, not only from mainland China but also several other countries and made this land their home.

And it is at Styletex that we meet Yee Shiou Sen who celebrates his 86th birthday on June 17. He is believed to be among the last of a couple of pioneers still left to tell the tales of those early days.

They heard, they came, they did not conquer but gently eased into and assimilated to their new lifestyle far away from home in Ceylon.

Ruggerite Yu Cey Chang

These were the first-generation Chinese that we were attempting to trace and Mr. Yee without hesitation invited us to his workplace, which he now shares with two of his sons, in Negombo.

The definition of ‘first-generation’ though seems ambiguous: “Designating the first of a generation to become a citizen in a new country or designating the first of a generation to be born in a country of parents who had emigrated.”

While many have been born in Sri Lanka to Chinese parents who had emigrated, which a walkabout in Maradana alone will prove where scattered along the main and narrow by-roads are dental technicians as well as textile sellers, it is hard to come by those ‘first’ settlers for time has taken its toll as evidenced by numerous tombstones at the General Cemetery (Kanatte) in Borella.

The 16-year-old Mr. Yee arrived by ship back in 1947, soon after World War II not from China but from Singapore, along with his parents and a brother and a sister. It was around April, he says for hesaw sawVesak for the first time in his adopted country a little later.

Businessman Yu Cey Chung

His father’s family departed their homeland in Hubei, central China, leaving behind their six-hectare paddy cultivations when civil war erupted, followed by the Japanese invasion. They walked through difficult terrain to the south of the country to board a ship for Singapore. “My father later got into the dental trade,” says Mr. Yee, adding, “Now I’m doing the same job.”

It is Yu Cey Chung who gives us the contact of Mr. Yee when we visit his office along Cotta Road in Borella. Here we also meet his brother, well-known rugby player Yu Cey Chang, who gives us an insight into their names. Yu is the father’s name, he says, pointing out that Chang is the given or first name and Cey denotes that he is from Ceylon.

Did you know that long before Sri Lanka had a dental school, dentistry was handled by dental technicians whose origins were in China, asks Chung who like his brother Chang were born in this country. Chung who imports dental stuff is the Vice President of the Sri Lanka Overseas Chinese Association and met Chinese President Xi Jinping during his visit here in 2014.

How the parents of Chang and Chung arrived here is fascinating. The Qing dynasty had fallen and Sun Yat-sen had taken over as the first President of the Republic of China founded in 1912. The Yu clan was living in the beautiful farming village of Tianmen or the ‘Gateway to Heaven’ in Hubei. Then came a great deluge, which inundated the village, leaving their larders bare. The migration began, in the footsteps of the village fool who had left earlier but returned prosperous, who told them that in Rangoon, Burma, the streets were paved with gold.

Thus, several families including the Yu grandparents loaded up their bullock carts and went to Rangoon, to find to their dismay that there was no gold. What could they do except beg and industrious as they were they looked around and noticed that the Burmese who were Buddhists would light candles and joss-sticks and also offer flowers at the temples.

“Our grandparents collected the wax and re-made candles and also paper flowers,” says Chung, reminiscing how as children they would see Chinese women, including their grandmother making flowers with kite paper and two ekels which they sold for five cents. “When you twist the ekels, the flowers blossomed out.”

It was in Burma that their father was born but the family did not linger there. Hearing that India was better, with thousands gathering for religious festivals, they emigrated once again in bullock carts as others had done before them to Calcutta. Their father, as a boy, along with his brothers would do circus acts such as juggling balls on the streets to earn a few cents.

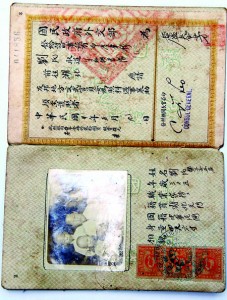

Once again they heard of “another nice country” and down they journeyed to Ceylon, says Chung, pulling out an old travel document of the whole family. They came by ship, landing at the Colombo Harbour, taking up residence in the Karpiri Mudukkuwa in the Pettah which was home to a motley group including Africans. Later they moved to Lockgate Lane in Hulftsdorp.

Yee Shiou Sen and Lee Shen Chi with two of their children

“My father was about eight,” says Chung, going back to stories told by him about how he would stand on a stool and help his father take dental impressions, at their first shop next to St. Philip de Neri’s Church on Olcott Mawatha.

All Hubei people who had left for Hong Kong, Indonesia, India, Pakistan and Ceylon were dental technicians. Another group, meanwhile, had come from Shandong Province taking to textile sales and running restaurants. Textile-sellers or dental technicians they fanned out from town to town, balancing bolts of cloth on their heads or carrying bags filled with dentures.

The Yu brothers have a hearty laugh as they recall how their father saw their mother, a pretty Sinhalese lass from Wattegama, at the Kandy Perahera. It was love at first sight and eloped they did, for her wealthy parents were furious. The Kandyan links could not be forgotten though and their mother insisted that they be educated at Trinity College and later at S. Thomas’ College, Mount Lavinia.

Hulftsdorp’s Lockgate Lane with two to three families was a tiny ‘Chinatown’ and people in the area remember the Chinese and point out two houses. Some have even seen the old deeds with Chinese names.

Sitting in the verandah of their home, 15-year-old Chung would without the knowledge of his parents enjoy a smoke with his grandmother, who was a “little thing” with “small feet”. He has even visited their village in Hubei in 1989, carrying with him a letter sent by a relative which his father, who had passed away eight years ago, had preserved for 35 long years. He has also traced his family going back 50 generations from meticulous records kept by the village headmen.

For Mr. Yee from Negombo, meanwhile, strange was the land they had come to. InSingaporethey had been among lots of Chinese. Suddenly, they were having “a difficult time” adjusting as well as trading for they did not understand this language. Spending a little time with relatives at Lockgate Lane, Mr. Yee’s family headed for Negombo and set up shop on Main Street. Mr. Yee would soon marry his relative andneighbourfrom Hulftsdorp, Lee Shen Chi, making Chang and Chung his nephews-in-law.

The family travel document of Yu Chin Chai (father of Chang and Chung), who was still a boy when they arrived in then Ceylon

He had “no choice” when his parents took the decision to marry him off at the tender age of 18 to this girl who had been born in the country and was fluent in its languages. “Life is like that,” smiles Mr. Yee, pulling out a photograph of a handsome younger self, his beautiful wife, who had died about five years ago, and two of their seven children.

Weddings were quite grand affairs with the bride hosting an all-girls’ party and the groom an all-boys’ party separately, the day before the wedding.

The wedding was at the then-famous Free China Hotel on York Street in Colombo, “now no more”, recalls Mr. Yee, when pressed, laughingly adding that “well we sit and eat”…….and eat they did, for there were more than 10 yummy dishes of “this and that” such as pumpkin soup and pork. The wedding photograph was captured at the Donald’s Studio in Maradana.

After the celebrations, the young bride came to Negombo to live in her husband’s family home, becoming the translator for the family’s dental (false teeth) business.

Working long hours, leisure was watching “full serials with all-fighting” (action movies) at the Asokamala (now the Regal) cinema in Negombo.

Chinese New Year was and still is special, with homes getting a thorough clean-up and the aroma of good food. The ancestral god is always remembered before the meal and at his altar, even now offerings of rice and plain tea are made for three days amidst lit candles and joss-sticks.

The Chinese are Buddhists and as we chat, in a corner of the still-dark textile-cum-dental-shop, for the lights have not been switched on yet, the flame of a tiny clay-lamp burns before a statue of the seated Buddha.

Among their customs is also the young paying obeisance to the old like the Sinhala Buddhist tradition, while when there is a death of an elder, his/her grandchildren would wear black headbands and arm-bands for at least three days as a mark of respect. “Now this is not being practised,” says Mr. Yee.

Going down memory lane to “ape kolu kale” (boyhood), he says that earlier they lived on Main Street by the side of the bridge, carrying out their small business. Life was good and food cheap. One-hundred tiger prawns cost only 90 cents and huge lagoon crabs, “this size” he says showing with his hands how big eka andak (one claw) would be, cost only 50 cents.

As Mr. Yee explains how he gets about his business, taking impressions and producing false teeth with imported material they have in stock, in walk two women. One wants “uda dath andak” (an upper denture) and when asked says that they have heard good things about Mr. Yee’s teeth. The women are from Kurana.

Tombstone at Kanatte of those no more

Many descendants of the likes of Mr. Yee are scattered across Colombo, Negombo, Kurunegala, Matugama, Galle,Trincomalee and Kandy. However, it was not until 2008 that the government under the leadership of Prime Minister Ratnasiri Wickremanayake, about whom they speak with much affection, lifted the early settlers from the oblivion of statelessness and offered them citizenship. By that time, though, many had emigrated elsewhere.

But there’s nothing like home, says Mr. Yee’s son, Chi Chung who too left, but later returned to the warmth of the only home he has known, while his father adds that this is why it is known as the Pearl of the Indian Ocean.

It is at Mr. Yee’s behest that we attempt to trace the descendants of the “first Chinaman” believed to have arrived back in the 1800s. “The talk is that Lim Pe Chan was a revolutionary. His tombstone is at the Kanatte.”

Having been pointed in the direction of a home next to the Infant Jesus Church at Slave Island, we traverse this highly populated area to trace the progeny of this first family. To no avail – but we do locate several tombstones at Kanatte, some inscribed in Chinese, with the births being in the 1800s.

Nostalgia turns to sadness when Mr. Yee says that “those days gone-by will not come back”, but perks up and adds that now the Chinese are a fine mix, holding varied positions in different professions.

Truly, these Chinese are a fine mix in the diverse tapestry that is Sri Lanka.