Visiting the cradle of Buddhism

Mihintale is the focal point during Poson Poya. Pilgrims in their thousands gather at Mihintale, the cradle of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, to commemorate the sacred day that Arahant Mahinda appeared at the ‘aradhana gala’, addressed the king who was on a hunting expedition, explained his mission, and convinced the king and his followers to accept Buddhism. The event took place in the 3rd century BC when King Devanampiya Tissa (250-210 BC) was ruling the country from Anuradhapura, the first royal capital.

Mihintale is the focal point during Poson Poya. Pilgrims in their thousands gather at Mihintale, the cradle of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, to commemorate the sacred day that Arahant Mahinda appeared at the ‘aradhana gala’, addressed the king who was on a hunting expedition, explained his mission, and convinced the king and his followers to accept Buddhism. The event took place in the 3rd century BC when King Devanampiya Tissa (250-210 BC) was ruling the country from Anuradhapura, the first royal capital.

The visit of Arahant Mahinda followed the meeting of the Third Council of the Sangha after the passing-away of the Buddha. It was held at Pataliputra during the time of Emperor Asoka, who embraced Buddhism following the carnage he witnessed during the war to conquer the kingdom of Kalinga around 260 BC. The conversion was brought about by a young monk, Nigrodha, the son of Asoka’s elder brother who lost his life during the struggle for power where Asoka was the victor.

Asoka renounced war altogether and decided to conquer the world without the use of weapons through ‘dhammavijaya’. Noticing several factions among the Sangha, he arranged for the pious Thera Moggaliputta Tissa to hold a meeting of the monks to purify the Sangha by expelling those who were not behaving properly. Among the decisions taken by the elders of the Sangha was to send missionaries to neighbouring countries and propagate the Theravada tradition, which was finalised by the Third Council. It is recorded that Thera Moggaliputta Tissa had decided that the principal missionary to each country must be accompanied by four other monks so that in addition to preaching the Dhamma, it would be possible to establish the Sangha thereby ensuring the continuance of Buddhism in those countries.

Mihintale, known as Mishrakakanda prior to the arrival of Arahant Mahinda, was surrounded by thick forest. Situated eight miles to the east of Anuradhapura, the king had chosen to come there on a hunting expedition on the day he encountered Arahant Mahinda. “The accounts of the conversion of the king and people to Buddhism, written by monks after that religion had secured for itself dominance over the minds of the people, are overlaid with edifying legends in which the miraculous element is conspicuous,” says Professor Senerat Paranavitana in ‘History of Ceylon’(1961). He adds: “Mahinda and his companions transport themselves by air from Vessagiri to Mihintale, gods are at hand to make smooth the path of the religious teachers, and impress the multitude with the efficacy of their doctrines. Earthquakes which do no harm to anyone vouch for the veracity of the prophesies ascribed to the Saint. At sermons preached on important occasions, the Devas in the congregation far outnumber the humans. Elephants, without anyone’s bidding, indicate to the king the exact spots on which sacred shrines are to be sited. In spite of the legendary overlay, the main event, i.e. that Buddhism was accepted by the people and the ruler, is attested by the presence at Mihintale and Anuradhapura of epigraphical and other monuments of a Buddhist character attributable to that period.”

Often we tend to forget that Sela Cetiya (stupa) at Mihintale is one of the sixteen places– ‘Solosmathana’ – hallowed by the visits of the Buddha.

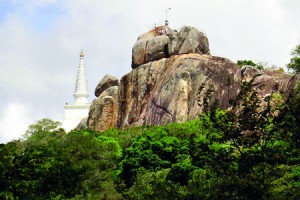

Reaching Mihintale, the devotees climb the impressive broad stairway made up of 1,640 granite slabs arranged in four flights. Well-grown ‘araliya’ trees adorn either side of the steps, providing shelter to the pilgrims. The slabs being laid at convenient distances to climb, it is a smooth ascent which the pilgrims hardy feel. Once the climb is over, they reach the Ambastala dagaba (Sela Cetiya) which marks the spot where the historic dialogue between Arahant Mahinda and the king took place. From here, they are directed to different places. The Maha Seya, the largest of the stupas at Mihintale can be spotted at the summit. Enshrined in it is a Hair Relic of the Buddha. On the other side is the ‘aradhana gala’.

A path takes the pilgrim down to a valley and to a steep rock wall. Well sheltered within, under a natural arch, is the ‘Mihindu guhava’ – the cave where Arahant Mahinda relaxed on a smooth flat slab of stone.

The Kantaka Cetiya, 40 feet in height with a circumference of 425 feet at the base, is famous for the ‘vahalkada’ (frontispiece) adorning the four sides of the stupa. Describing the architectural features of a ‘vahalkada’ Paranavitana says it consists of “a series of horizontal bands separated by string courses which are variously ornamented. The upper part of the frontispieces took the form of ‘vimanas’ containing figures of divine beings in the niches.” They are built alongside the altars where devotees offer flowers.

Having done a comprehensive study of the Mihintale complex, Sinhala scholar Professor J.B. Disanayaka states that compared with the stupas in Anuradhapura, those at Mihintale are simple in structure, and modest in size. In his publication, ‘Mihintale’ (1987), he describes the features of a stupa: “It can be divided structurally into three parts: base, dome and superstructure. The base consists of three concentric terraces of berms,’pesa vavalu’, some of which were moulded with blocks of white limestone, as those at Kantaka Cetiya. It is conjectured that these terraces were originally, either procession paths for ‘pradakshina’ (circumambulation), or altars for flower offerings.

The dome, hemispherical in form is a brick structure that contains a relic chamber, ‘dhatu garbha’ in which are deposited the relics of the personage in whose memory the stupa was erected. The shape of the dome is varied. The shapes recognised by old craftsmen include a heap of paddy (‘dhanyakara’), the temple bell (‘ghantakara’), the filled pot (‘ghatakara’), a bubble of water (‘bublukara’) and the lotus flower (‘padmakara’).

The superstructure, in its most developed form, consists of a solid cube, ‘hatares kotuva’, the four sides of which are ornamented with designs of railing and discs; a cylindrical shaft,‘devata kyuva’; a brick spire, ‘kot kerella’, resembling the umbrellas of Indian stupas and finally, a pinnacle, ‘kota’.

Pointing out that the story of Sinhala sculpture also begins at Mihintale, Prof. Disanayaka states that the objective of the early Sinhala sculptor was mainly decorative – to embellish the various architectural features of the stupas and other monastic buildings. The best collection of sculptures at Mihintale is found in the eastern ‘vahalkada’ of the Kantaka cetiya. The ‘muragal’ (guardstones), ‘koravakgal’ (balustrades), ‘sandakada pahan’ (moonstones) and ‘purma ghata’ (full-pots) are among pieces of sculpture that are characteristically Sinhala.

Being rather anxious to get to Anuradhapura and do the ‘vata vandanawa’ to worship the ‘Atamasthana’- the eight places of worship, pilgrims tend to miss out most of the interesting places at Mihintale. The grandeur of Mihintale was lost along with the decay and destruction of the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa kingdoms.

Pioneering archaeologists, H.C.P. Bell and Senarat Paranavitana were responsible for the rediscovery of Mihintale.