Sunday Times 2

Trump’s foreign policy reversals

View(s):By Martin Feldstein

CAMBRIDGE – During his first 100 days in office, US President Donald Trump reversed many of the major positions on defence and trade policy that he had advocated during his presidential campaign. And these reversals have yielded some positive results.

Trump’s policy toward China is the best example. During the campaign, Trump promised to label China a currency manipulator on his first day in office; end the “One China” policy (recognising Taiwan as part of greater China) that has long guided Sino-American relations; and impose a high tariff on Chinese imports, to shrink the bilateral trade deficit.

None of that happened. Trump did not label China a currency manipulator upon taking office. When the US Treasury last month conducted its scheduled review of Chinese currency policy, it concluded that China was not a currency manipulator.

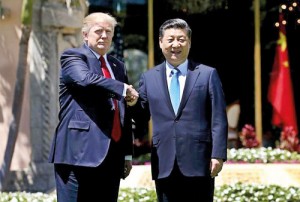

U.S. President Donald Trump (L) and China's President Xi Jinping shake hands while walking. Pic Reuters

Trump quickly reversed himself on the One China policy as well, telling Chinese President Xi Jinping that the United States would continue to adhere to it and inviting Xi to visit him at his Mar-a-Lago retreat in Florida.

That meeting led to a trade negotiation led by Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross in which China agreed to open its market to US beef and various financial services, and the US agreed to sell liquefied natural gas to China. The result will be a decline in the US trade deficit with China, with no increase in tariffs.

Reducing the bilateral trade deficit will not decrease the overall US trade deficit, because that is the result of the difference between investment and saving in the US. A lower bilateral trade deficit with China will just mean a larger trade deficit – or a smaller surplus – with some other country. Nonetheless, while the Trump administration is wrong to put so much emphasis on trade deficits with individual countries, doing so in China’s case has had the favourable effect of leading to policies that reduce foreign barriers to US exports.

Elsewhere in Asia, Trump warned South Korea and Japan during his campaign that they could no longer count on America’s decades-long security guarantee. But almost immediately after Trump assumed office, Defence Secretary James Mattis flew to Seoul to reassure the Koreans, and the administration moved ahead with installing the advanced Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) anti-missile system in South Korea, despite Chinese objections. And then Mattis flew to Japan to offer the Japanese a similar reassurance of continued US military support.

Likewise, candidate Trump, complaining that NATO’s European members had not met their commitments to spend 2% of GDP on defence, vowed to reduce US military spending in Europe. He also criticised NATO for being unprepared to join the US-led fight against the Islamic State (ISIS).

And yet Trump has backed away from his threat, and the Europeans have moved a little in the direction that the US has urged. Trump’s proposed federal budget calls for an increase in US military spending in Europe, while NATO’s European members have agreed to increase their military spending toward the 2%-of-GDP goal (though not as rapidly as Trump would like). And the North Atlantic Council, NATO’s governing body, recently voted to join the campaign against ISIS (though not in a combat role).

Trump’s campaign threat to tear up the North American Free Trade Agreement unless better terms could be agreed has led to renewed negotiations, led by the US Special Trade Representative. It is too soon to tell what will result from the talks. It is to be hoped that the emphasis will be on further reductions in specific trade barriers that impede US exports to Canada and Mexico. It would be a mistake, for example, to limit Canada’s lumber exports to the US on the grounds that the Canadian government subsidises them. Import barriers would only hurt US builders and homebuyers.

I don’t know why President Trump has shifted to positions so different from those he advocated during the campaign. Have his cabinet-level officials persuaded him that his earlier positions were wrong? Does he believe in delegating decision-making on these issues to those officials? Or were his campaign promises aimed at attracting voters rather than revealing his own views? We probably will never know.

Domestic policy is different. The administration recently released a ten-year budget plan that has been rightly criticised for its lack of coherence and its failure to describe explicit tax policies. But budget policies are different from international security policies, because the US Congress makes the detailed decisions on spending and taxes.

Trump’s plan proposes domestic spending cuts that he must know Congress will not accept. And the projection of a balanced budget at the end of the ten years is needed under congressional rules to make permanent whatever tax changes occur. But for the details of the potential tax changes, I still look to the plans developed over the past several years by House Speaker Paul Ryan and his colleagues.

Despite Trump’s campaign (and his erratic statements and capricious tweets since he assumed office), his administration’s actual defence and trade policies are on the right path. I remain hopeful that the tax policies developed in the Congress will provide a framework for desirable reforms of personal and corporate taxation.

(The writer is Professor of Economics at Harvard University, President Emeritus of the National Bureau of Economic Research and chaired President Ronald Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers from 1982 to 1984.)

Courtesy : Project Syndicate, 2017. Exclusive to the Sunday Times.

www.project-syndicate.org