News

Watch out for melioidosis after disaster

View(s):- Red alert from expert Dr. Enoka Corea on this ‘great mimic’ of rat fever and TB

- Early detection key to saving lives

By Kumudini Hettiarachchi

As flood waters recede, a strong red flag is being waved on the need to watch out for melioidosis. “Be alert for an increase in melioidosis cases,” urges Senior Lecturer in Microbiology Dr. Enoka Corea of the Medical Faculty, University of Colombo, who has engaged in much research on the bug which causes this disease.

Bulathsinhala-Horana Road: Rains, floods and landslides could be precursors of melioidosis. Pic by Amila Gamage

She points out that exactly a year ago (2016) in June there was “a high spike” in the number of cases 2-4 weeks after the floods.

The danger, of course, is that this bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei is a ‘great mimic’ and melioidosis can easily be misdiagnosed as leptospirosis (rat fever), tuberculosis (TB) or pneumonia. Tropical countries close to the Equator including Sri Lanka harbour this bacterium.

Dr. Corea points out that these bacteria rise rapidly from muddy and watery soil during the monsoons as well as disasters such as floods and landslides. With melioidosis having a high death (mortality) rate of 1 in 4, early identification is the key to saving lives.

The bug takes a silvery metallic sheen on culture and sometimes gradually wrinkles up, it is learnt, while it has an antibiotic-sensitive pattern which is peculiar. In a gram stain under the microscope, it has a safety-pin appearance.

Dr. Corea reiterates:

Exposure to B. pseudomallei occurs outdoors, as it is a soil saprophyte (a bacterium that grows on dead or decaying organic matter), especially in muddy soil.

Dr. Enoka Corea

While anyone can get infected, at highest risk are people who have occupational exposure to soil and water such as paddy farmers, other cultivators, livestock farmers, military personnel and construction workers. Even those who engage in gardening, children if they play in muddy water or those wading through flood waters are vulnerable.

Going about barefoot in mud or muddy water raises the risk of catching melioidosis.

It is not a ‘primary’ pathogen (something which causes disease commonly), but an ‘accidental’ one, acquired by exposure to soil and water.

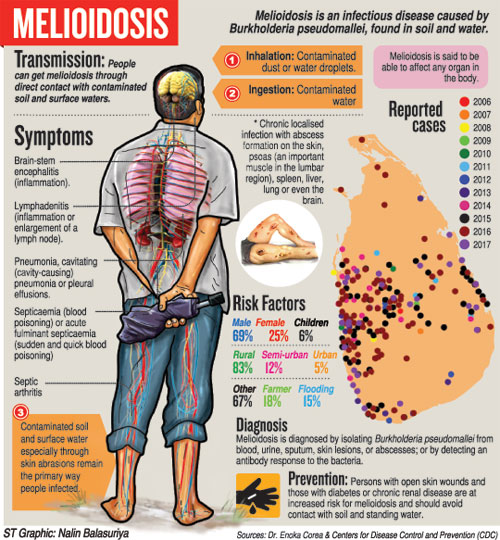

The mode of transmission is not clear but the bug is most likely to enter the human body through the skin, if there are breaks or cuts in it, and also the mucous membranes. Inhalation plays a role when soil or water is aerosolized (becomes a fine spray), during heavy rains and floods. Ingestion may also cause small outbreaks due to a common water source.

The incubation period (time between infection and appearance of symptoms) ranges from a few days to 10 days or even many years. Sometimes, even after melioidosis is treated successfully, there could be a relapse, it is learnt.

The symptoms of melioidosis are:

Chronic localised infection with abscess formation on the skin, psoas (an important muscle in the lumbar region), spleen, liver, lung or even brain.

Pneumonia, cavitating (cavity-causing) pneumonia or pleural effusions.

Septicaemia (blood poisoning) or acute fulminant septicaemia (sudden and quick blood poisoning).

Septic arthritis.

Lymphadenitis (inflammation or enlargement of a lymph node).

Brain-stem encephalitis (inflammation).

With melioidosis being an “opportunistic” infection, those with diabetes, chronic renal failure, renal transplants, thalassaemia, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) or alcoholism are more vulnerable to it, it is understood.

A culture is the ‘gold standard’ test, says Dr Corea, and the treatment intravenous-administered antibiotics, followed by oral eradication treatment to prevent a relapse.

Incidentally, a mathematical modelling of the incidence of melioidosis published in the journal ‘Nature – Microbiology’ last year predicted that South Asia will have the highest burden and Sri Lanka 1,881 cases per year with 619 deaths.

“This is why we need to take heed and watch out for melioidosis,” adds Dr. Corea.