Village ‘mystery box’ for MasterChef

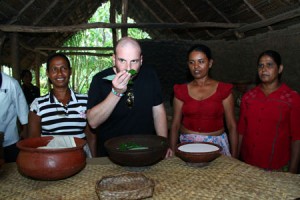

George Calombaris takes a bite of the kernel of a local thirst quencher ’kurumba’. Pix by Indika Handuwala

George Calombaris watches a woman roughly grind mint leaves into a bright green paste. Crushed between the stone surfaces of her mortar and pestle, their sharp fragrance drifts through the small clearing around a village home. His hosts, Cinnamon Life, flew Calombaris down from Colombo to Dambulla only this morning, and it took a car, a boat and a brisk walk to bring him here. He is visibly tired but still paying close attention.

This session with home cooks in rural Sri Lanka on Thursday has been an instructive one for the chef most famous for being one of the trio of MasterChef Australia judges: he has learnt that you can coax a second and third ‘milk’ out of a coconut that has already produced a first batch of thick and creamy liquid; he has improved his fine motor skills through lessons in how to eat rice and curry with his fingers; he has discovered that dried cow dung is still used to patch surfaces in village homes (but only after he leaned on a wall coated in the stuff). Unlikely as it seems, something about this experience also reminded Calombaris of his grandmother.

He called her Yiayia, as Greek children are taught to do. The story that came to his mind dates back to her arrival in Australia as an immigrant. Then his Yiayia brought with her her own mortar and pestle, obviously considering it essential equipment. But customs officers felt differently – they had not seen one before and confiscated it on sight, convinced that it was a weapon.

But their kitchen equipment was not the only thing that singled out the Calombaris family. The first generation to be raised in Australia boasted a cocktail of ethnic influences: George’s father was born in Italy to Greek parents. A mechanical engineer, Jim Calombaris spoke five languages. George’s mother Mary found her way to Australia, having fled Cyprus on the back of a Turkish invasion. Initially, Mary’s family could only afford a rat-infested house. She went to work to earn a living as a seamstress.

Their businesses would do well, but the Calombaris’ kitchen remained unconventional. When it was time for a big party, Jim would line the bathtub with plastic sheets and marinate a whole lamb in it, and every time they returned from midnight mass, it was to bowls full of hot soup. Even if Calombaris had not realised something was different about his family, it was pointed out to him. “Even though I was an Aussie boy, I was from an ethnic background, and I have been spoken to personally in ways that a person should never have been spoken to,” he says. “I hate how racist we are in Australia.”

It’s an awareness that Calombaris has carried with him all his life, and one that has shaped his career in an unexpected way. After all, the man is part of a TV show famed for its celebration of cuisine and culture. In 2017, MasterChef is remarkably diverse. Rashedul Alam was born in Bangladesh; Ben Ungermann is of mixed Dutch and Indonesian heritage; Bryan Zhu is one of five sons born to a Chinese immigrant couple; Diana Chan grew up in Malaysia. Then there’s Ray Silva whose Sri Lankan roots have fans on this island rooting for him.

With an emphasis on memory and feeling, MasterChef judges (and audiences) have always warmed to stories about family and culture. In this kitchen at least, different can be very good. “Food is this common language we all speak,” says Colombaris. “Masterchef is multicultural. It’s diverse. It’s accepting. It’s not racist. If the show had a voice, it would say welcome to all people with open arms, with an open heart. Anyone who has a love affair with food, just come,” says Colombaris. “I’m really proud of that and that’s why I think the show resonates around the world.”

With mortar and pestle: Bringing back memories of his Greek grandmother-Yiayia

But the real heart of the show for fans may just be the judges. Matt,George and Gary are the one constant, and they’ve become popular enough that when the judges landed in New Delhi on a visit awhile back, they found hundreds of people waiting to greet them. “It’s strange, it’s not like you are a band that has a single that just went to No.1,” says Colombaris. “We are just cooks. We’re not saving lives.” He thinks people turn out for a simpler reason: “We make them happy.”

The three men go back a long way. Gary and George have known each other for over two decades, and their post-MasterChef relationship with Matt spills over the boundaries of the show. They spend a lot of time together, and their families are in and out of each other’s homes.

In fact, they were shooting MasterChef when Colombaris found himself mired in controversy over a pay scandal. In April, the story broke that nearly 200 staff were underpaid a combined sum of $2.6 million due to a procedural error. Another group of employees was overpaid. Though there was a delay in dealing with the issue, the company compensated affected employees. But Colombaris’ reputation took a hit.

He later told News Corp Australia that there was no avoiding how badly they had messed up and that he was determined to accept responsibility, to “take it on the chin.” He added: “If we are to take this company to the next level, meaning global, we can’t run it like a milk bar and that is how I was running it.”

For the 38-year-old, the crisis has been a test. This is a chef who has never been short on accolades. Just a selection: in 2004, he was one of the top 40 most influential chefs in the world and young chef of the year; he was chef of the year again in 2008 and entrepreneur of the year, 2011. His restaurants have won a range of Fairfax Media Good Food Guide awards. He has published five books and represented Australia at Bocuse d’Or, often described as the Olympics of the culinary world. But post the pay scandal, Colombaris found himself battling public opinion. The rest of this year will see if he can recover the goodwill that once came so easily.

MasterChef can only help. On the show, Colombaris has become the judge who goes up to contestants in a crisis. He consoles them, he cheers them on, and when required, he pushes them hard. That moment of crippling self-doubt is one he understands. “It resonates for me, because I have fallen apart plenty of times,” he says. “Cooking is actually pretty easy. You can pull a plumber off the street and teach him to cook. The difficultly lies in creativity, in maintaining mental control, so that things don’t get on top of you.” Viewers, he says, only see 10 percent of what contestants go through on MasterChef. “If we showed you everything, we couldn’t have a show, we’d have to have a channel.”

MasterChef absorbs four or five months of Colombaris’ time. There was a time when they did more – when there was a celebrity version and a superstar version and even a junior version. “It was too much and too much of a commitment for the consumer,” says Colombaris, comparing the present iteration of the show to the English Premier League which has its own season. Limiting it in this way has meant that when the show is on, it’s really delivering: every year the contestants are better, the stars are bigger and the challenges are more crazily ambitious. Colombaris couldn’t be more pleased with how it’s going. But that doesn’t mean he can’t see an end in sight.

Selfie time: George Calombaris can’t resist Habarana’s lake setting and below, getting a whiff of village flavours. Pix by Indika Handuwala

“I can tell you MasterChef is definitely going to go away, but I can’t predict when that will be,” he says. Part of his comfort in the idea comes from his own notion of not standing still. In fact, he is looking at the most ambitious expansion in his career over the next few years as he and his partner Radek Sali roll out 50 new Jimmy Grants restaurants as well as his Gazi eatery in new locations around Australia,Indonesia and America. As we speak, Colombaris already has the beginnings of an empire with 11 venues and over 400 staff. All this froma first job of washing dishes at the back of a restaurant.

“I am at a new chapter in my professional life. It’s been 21 years,” he says contemplatively, adding that in many ways, things are still the same. He got here, he says, by just setting out to do each new thing – dish washer, apprentice, chef, reality TV judge, restauranteur – to the best of his ability and, whatever 2017 holds, that’s still what he intends to do. “I was constantly looking around to make sure I was ahead of the pack. Wanting to be the best I could,” he says. “Potentially, nothing has changed. I still want to create the best experiences for people.”