Lionel Wendt: Recovery and dispersal

View(s):By Manel Fonseka

When I first wrote about Lionel Wendt in 1994, the person and the artist seemed to be almost forgotten. Few visitors to the popular theatre and art gallery that bear his name had any idea who he was or were even curious about him. He had become like a personality behind a well-worn street name, familiar but unknown. It was as if he had disappeared along with his house, ‘Alborada’ (‘morning-song’ in Spanish) when the latter was demolished in 1950 for the present Wendt Memorial complex.

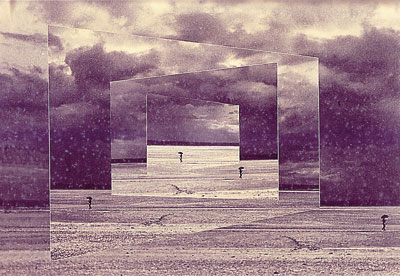

Adventure in Space, n.d, Courtesy LWMF

His memory was retained almost solely perhaps by those who possessed a copy of that beautiful book Lionel Wendt’s Ceylon. Underwritten by his friend Harold Peiris and published by Lincoln-Prager, London in 1950 for the Lionel Wendt Memorial Fund (LWMF) it has now become a collector’s item. It was planned when Wendt’s younger brother Harry Wendt was still alive, and was to be the first of three volumes of photographs. Five thousand copies were published. However, the book did not sell easily and subsequent volumes were abandoned.

The search for Wendt

My own search for Lionel Wendt came about quite by accident. In 1993 I began to work on an article in connection with the 50th anniversary (August 29, 1993) of the founding of the `43 Group in Lionel Wendt’s house. It struck me that outside the Sapumal Foundation there was no sizeable (or publicly accessible) collection of the work of these artists. My husband had told me how much his own interest in modern art was inspired and influenced during his schooldays by the paintings that used to hang in the foyer of the Wendt theatre. But I had never seen them – or, at least, noticed them. They were part of an impressive collection built up by Lionel Wendt, left to his brother Harry and then to Harold Peiris, who gave it to the Fund. A passing reference in Neville Weereratne’s book (The `43 Group: A Chronicle of Fifty Years in the Art of Sri Lanka, 1993) to the decision in 1963 to sell these paintings, put paid to my article by launching me on a journey to discover the ‘lost’ collection instead.

Weereratne regrets this loss: ‘They made a formidable gallery that would indeed have served well as the nucleus of a national collection.’ He would probably be glad to learn that Keyt’s Yama and Savitri (1938), one of the finest paintings in the collection, finally found its way home after a long sojourn abroad and was acquired for the Presidential Collection.My search for the Wendt painting collection, however, turned out to be a first step on a very different journey – the recovery or, rather, re-discovery, of Lionel Wendt himself. It opened up a whole new world, taking me to unexpected places and introducing me to people I would have been the poorer for not knowing. Among them were former friends and pupils of Lionel Wendt’s, like the pianist Hilda Naidu, who gave me one of my most cherished possessions, a large original print of the famous self-portrait – the one that hangs in the foyer of the Wendt theatre. She also confirmed, quite by accident, in one of our many conversations, my hunch that it was his voice concealed under a pen name behind various satirical writings. Almost everyone I met in this way urged me to write a book about him.

Lionel Wendt, Self portrait. c. 1937. Private collection, Colombo. Courtesy Lionel Wendt Memorial Fund

Ian Goonetileke, of course, has revealed something of Wendt’s influence on and relationship with George Keyt, related to him over many years of friendship with the painter. Former Wendt Memorial trustee Shelagh Goonewardene wrote about ‘Wendt’s contribution to art’ in her Sunday Times column on theatre in 1980, reproducing it as a chapter in her book This Total Art: Perceptions of Sri Lankan Theatre, in December 1994.Air Lanka’s in-flight magazine, Serendib reprinted Len van Geyzel’s introduction to Lionel Wendt’s Ceylon in 1989, with several illustrations from the book. Painter and writer Neville Weereratne had a chapter on ‘the Wendt contribution’ in his book on the `43 Group (1993). Scholar Ellen Dissanayake published an article she had written about ten years earlier – ‘Renaissance Man: Lionel Wendt’ – in Serendib’s issue for July/August 1994. An inferior reprint of Lionel Wendt’s Ceylon was produced by an Indian publisher in 1995. A poor substitute for the original edition, it blatantly omits the 1950 publishing data, giving the impression that the first edition was also by the same publisher. I believe that the LWMF was not consulted about this reprint and it is unlikely that copyright permission was obtained, even for Len van Geyzel’s introduction.

The turning-point; August 1994

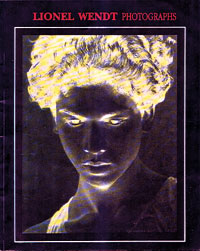

It was not until August 1994 when Lionel Wendt: Photographs, an exhibition at the Lionel Wendt Memorial Gallery, took place, that the spotlight on Wendt unleashed a new wave of interest in his photographic achievement. For 35 years, Sri Lankans had no opportunity to see the work of their most famous photo-artist. Since the exhibition and sale of his photographs at the opening of the Lionel Wendt Memorial Art Gallery in 1959, there seems to have been no public showing of Wendt’s work until this exhibition in August 1994. On that memorable occasion, one hundred original prints in excellent condition from the collection of the LWMF were displayed for a week at the Lionel Wendt Art Gallery. The exhibition was organised by the Fund and the Deutsche Bank, who also sponsored it and published the catalogue.

It evoked great interest, especially from a younger generation of photographers who had never seen original work by Lionel Wendt. Three hundred copies of the catalogue sold in two days and almost five hundred more before the end of the week. Every photograph from the exhibition was reproduced. My contribution was as a writer to the catalogue where I published descriptions and notes about the photographs along with an essay: ‘Rediscovering Lionel Wendt’.

Invaded…Desolate. n.d. Courtesy LWMF

International recognition and the loss of heritage

At the time I began my ‘search’ (July 1993), few people seemed to be interested in what Wendt had collected, but some, at least, were interested in his photographs. This ‘some’ needs emphasis because it was, in fact, surprising to see how little interest there was, at this stage, in Wendt’s photography. It was encouraging, however, to find that most of the original photo-prints reproduced in Lionel Wendt’s Ceylon were well-preserved by the Fund, together with a number of other ‘original’ photo-prints.

Lionel Wendt: Photographs, exhibition catalogue, 1994, Colombo, Courtesy LWMF

But apart from this collection of photographs, there is, or was until recently, another major collection of Wendt’s work in Sri Lanka – the largest perhaps, anywhere in the world. I was invited to view it in 1993, and realizing how difficult it was for the owners to continue to look after it, I tried hard to find a person or institution in Sri Lanka to buy it and preserve it ‘for the country’ – but failed. At the time I was also innocent of the origins of these photographs. I have subsequently come to learn that they had in fact been stored for years in a commercial firm while building work was underway at the LWMF. The current ‘owner’ had found them and appropriated them instead of returning them to the Fund. An opportunity to see something of this magnificent but contentious collection came two years after the 1994 exhibition, when a selection was displayed and sold at Gallery 706 in Colombo. Two years later a number of works were exhibited for sale by Paradise Road Gallery. From this time on, the buying and selling of original Lionel Wendt prints and the drain abroad began, what can only described as the re-discovery of his commercial value. One has to ask if in Sri Lanka, as usual, we seem to be as eager to get rid of what we have, as people abroad are eager to relieve us of it.

The outcome of this commercial interest can be evidenced in the marketing of Wendt’s work by Dutch gallery owner Ton Peek who mounted several exhibitions in the late 1990s. In 1999 he exhibited forty ‘vintage silver prints’ (sic) in the Paris Photo Fair 99 held by the International European Salon of Photography, in the Louvre. These were described as ‘mostly collage-portraits of Ceylon men’. Peek’s notes say, ‘Wendt had rarely left Ceylon, at that time a Dutch possession’ (sic).

Arguments for keeping and safeguarding our cultural heritage and preventing its export have been made ad nauseam. I am reminded of the image of a leaning signpost in Ceylon which Wendt titled: The Point Beyond Which Everything Repeats Itself. I wonder if those of us who share this point of view will look like desolate leaning signposts to future generations. It is perhaps symbolic that the editors of Lionel Wendt’s Ceylon re-titled the picture: Invaded…Desolate.

I know of one other small but very precious and revealing collection of photographs by Lionel Wendt owned by a descendant of the person to whom Wendt gave them. I had the privilege of seeing them in a rush encounter with the owner sitting in a railway station café – we had each come from separate parts of the country for the meeting. The photographs make up a book and say as much about the photographer as they do about his subject; they show a Wendt very different from the image many have of him. I have longed to be allowed to have copies and have waited nigh on 20 years for this. Without some part of them, any book I wrote would be incomplete.

(December 2000)

(A version of this article was published in The Sunday Observer, 17 December 2000 under the title ‘Lionel Wendt: Disappearance and Discovery’.)

2017: Resurgence abroad The publication of his photographs in Lionel Wendt: A Centennial Tribute by the LWMF in 2000 on the 100th anniversary of his birth, launched this passionately Sri Lankan master’s work into the new millennium. Since writing about my ‘re-discovery of Lionel Wendt’ in 1994 I have watched his work become the subject of much international interest. In 2003 the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum in Japan, exhibited sixty prints from the collections of Nalin Tomar and Mahijit Singh in India, in The Gaze of Modernity: Photographs by Lionel Wendt, from August 21 to October 28. I now believe their photographs came from the contentious collection in Colombo referred to in the article alongside. "I was invited to contribute a text for the exhibition catalogue ‘Lionel Wendt and Sri Lankan Modernism’ for which I also identified and annotated the photographs as part of my research.” Some time later I discovered that the Fukuoka acquired some of the works from Nalin Tomar for its permanent collection. His collection appeared again, some ten years later, this time as part of a commercial exhibition held at Jhaveri Contemporary in Mumbai, of eighteen works by Wendt together with paintings by Amrita Sher-gil. The same gallery exhibited thirty-six works at the commercial art fair Frieze Masters 2014 in Regents Park, London. When living in New Delhi in 2001 my husband sent a request to Tomar for me to see his collection. He refused. It is ironic that two years later I was writing for an exhibition of his collection, something I was ignorant of until the museum sent me a copy of the catalogue in which I had written! The dispersal of Wendt’s work through Jhaveri Contemporary into numerous private and public collections internationally has undoubtedly led to much intrigue and curiosity about the artist. Foreign curators have come to Sri Lanka in search of Lionel Wendt. As a result his work is currently featured in documenta being held in Athens from April 8 to July 16 2017. While the show exposes his work it also exposes how the intrigue and curiosity for Wendt has stopped short of looking at the provenance issues that surround a large body of his photographs. A parallel exhibition, described by its organisers as a ‘large-scale retrospective exhibit at Huis Marseille, which will shine a spotlight on the fascinating work of this photographer in all its facets’ opened on 10th June in the Netherlands. The exhibition includes over one hundred and forty prints by Wendt, most of which originate from the galleries of Ton Peek and Jhaveri Contemporary. Both these commercial galleries, profit from the museum presentation of the work, which they have initiated and collaborated on. The involvement of the art market at such close quarters to the scholarly curation of Wendt’s work raises more questions than answers. Moreover Ton Peek is also selling ten works by Wendt which he has reprinted and is trying to sell in boxed editions of prints. To truly show Wendt’s work, ‘in all its facets’, as this exhibition claims to be doing, one would also need to see this as a collection that rightly belongs to the LWMF but has been sold at home and abroad because people who had no right to them could not see beyond their financial value and their own gain. But perhaps this is a question that is yet to be addressed by those who are ‘re-discovering Lionel Wendt’. | |