News

The battle to keep Sinhala alive in an American University

Scholars at the Cornell University, USA, are fighting to keep alive a decades-old Sinhala language programme that is facing closure owing to funding cuts.

Cornell, a renowned private Ivy League institution, is the only university outside Sri Lanka to offer a full curriculum of study in Sinhala. About half of the funding for the course is external, primarily from the US Government’s Department of Education. The rest is from the university.

But Cornell’s administration has decided to prune its contribution to the Sinhala programme by next year and to divert these funds to disciplines which students find “more attractive”.

This will effectively turn Sinhala studies into a part-time course that can no longer retain a highly-qualified professor, while the programme will lose its curriculum status before it is ultimately closed down.

Cornell’s South Asia Programme Director Anne M Blackburn is leading the initiative to prevent this from happening. The Sinhala language programme was established around 1970 by Prof James Gair in close collaboration with Prof W.S. Karunatillake from the University of Kelaniya.

It was the first and only such course in the Western hemisphere at the time.

Anne M Blackburn speaking at Peradeniya University

A professor of South Asia Studies and of Buddhist Studies herself, Ms Blackburn is a fluent Sinhala speaker. She first came to Sri Lanka as an undergrad on the Intercollegiate Sri Lanka Educational (ISLE) initiative connected to the Peradeniya University.

“We had lectures from some of the best professors there on history, politics, religion and economics,” she told the Sunday Times via email from New York. She learnt Sinhala from Kamini de Abrew who trained Peace Corps volunteers and also Cornell’s incumbent Senior Lecturer in Sinhala, Bandara Herath.

Sinhala is special to her, Prof Blackburn said. It helped open up a world of exploring Sri Lanka and building relationships with people. Had Tamil been offered by the ISLE programme, she would have studied that too.

Today, she uses Sinhala and Pali to read historical documents related to Buddhist and Sri Lankan history, literature and intellectual history.

“Colloquial Sinhala has allowed me to travel much of the island comfortably and converse on history and literature with Buddhist monks,” she continued. It has helped her feel closer to the country, emotionally as well as intellectually.

Joining forces to save the Sinhala course are Mr Herath, Abby Cohn — Professor of Linguistics and incoming Director of Cornell’s Southeast Asia Programme who shares a concern with Prof Blackburn about protecting Asian languages — and Hirokazu Miyazaki,Cornell’s Einaudi Centre International Studies Director, who understands that protecting foreign languages at Cornell is critical to sustaining international studies programmes.

But they have a daunting task ahead. Among other things, they will have to convince potential funders (including the public) that Cornell’s Sinhala language course is worth putting money into. As part of their strategy, they are reaching out to the Sri Lankan Government for a one-time contribution to a trust fund that will sustain the Sinhala programme.

They will also raise awareness in Sri Lanka in the hope of getting financial support from Sri Lankans; mobilise the Sri Lankan American community to raise funds; appeal to the Cornell University College of Arts and Sciences to maintain its current commitment; and lobby the university administration with a view to postponing its decision to reduce funds.

“Most importantly, we are looking for ambitious endowment funding,” Prof Blackburn said. “We need US$2 million in endowment to fully secure the Sinhala programme. Only an endowment will make Cornell Sinhala fully safe for future generations.” Full admission records for the Sinhala programme going back to its inception in the 1970s are not available.

But recent information points to total enrolment figures of between 300 and 500 students. Prof Blackburn says the numbers are not the only indication of the impact of the programme.

Cornell has been the only continual source of Sinhala teaching and learning materials for acquisition of Sinhala by those for whom Sinhala is not a first language. Cornell’s Sinhala text books are used much beyond the students of the University or its affiliated summer programme, including by business and diplomatic professionals.

Liyanage Amarakeerthi, Professor in Sinhala at the University of Peradeniya, taught for four years at Cornell. He says the course produced many speakers of Sinhala in America, like Anne Blackburn.

They subsequently published books and papers that make the case that Sinhala language and culture are instrumental in understanding South Asia.

“In fact, much of the academic work in English or Sinhala literature and culture have been done by those scholars who have directly or indirectly benefited from Cornell’s Sinhala programme,” he observed. But Prof Amarakeerthi is not convinced that the Sri Lankan Government will contribute financially towards ensuring the course’s continuity. The usual expectation is for the US to assist Sri Lanka, not the other way around.

What might work better is a campaign among the Sri Lankan community in the US: “We had several Sri Lankan American students and the Sinhala community is growing in and around New York. “They are also doing quite well financially. That might be the right way to go.”

Generally, around half of the enrollments in the Sinhala programme are Sri Lankan, Sri Lankan-origin or heritage students. The rest have no Sri Lankan connections but are taking the course for research preparation or other personal interest. And admissions, Prof Blackburn says, are rising–greatly due to the excellence of Mr Herath.

“Sri Lanka’s post-war context has also made studying the language more attractive to students with or without Sri Lankan heritage connections,” she noted.

“Having Sinhala taught outside Sri Lanka — especially at a prestigious Ivy League university — is a symbolic affirmation of the island’s global importance and the capacity of Sri Lankans to create and protect that symbol through endowment.”

“The argument for national development is also valuable,” she pressed on. “All nations need experts to enable their ongoing development. Those experts are most effective in Sri Lanka if they have linguistic and cultural background before undertaking projects.”

If diaspora students of Sri Lankan heritage learn Sinhala and Tamil, they can do more for their country, Prof Blackburn maintained: “I regularly see their interest in this and it’s a big motivator. So our Sinhala programme is part of building and protecting the bridge between diaspora and homeland, which is at risk with children born abroad.”

The scholars believe that, from a US national perspective, less commonly taught languages — including Sinhala — should be protected within universities to maintain foundational global expertise.

“We can anticipate a growing importance of Sri Lanka-related knowledge to the US in the next several decades as China’s activities in the Indian Ocean region continue to expand under the One-Belt-One-Road initiative and Sri Lanka’s economy continues to transform in the post-war period,” she said.

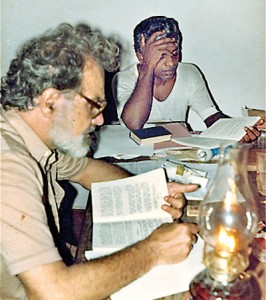

| Prof. Gair: The scholarly power behind Sri Lankan studies Linguist James Wells Gair is known for his pioneering study of South Asian languages and their underlying relation to other countries. He died at the age of 88 in Ithaca, New York, last year. Prof Gair had a BA magna cum laude and an MA in English from the University of Buffalo and gained a PhD in Linguistics from Cornell University.  Prof.James Wells Gair with Prof W S Karunatillake He received an honorary Doctor of Letters from the Kelaniya University which also awarded him the title of ‘Sahitya Chakravartin’. He was a Professor of Linguistics at Cornell till his retirement in 2000, then Emeritus. Not only did Prof Gair help to build and sustain Cornell’s South Asia programme, his extensive scholarship steered the programme to its continuing commitment to Sri Lankan studies, and its pre-eminent place for Sri Lankan studies in the world, establishing the Sinhala language course. His early book, ‘Colloquial Sinhalese Clause Structures’, is now a classic. Prof Gair’s long collaboration with Prof W S Karunatillake began with the latter’s studies at Cornell as a graduate student beginning in 1965. It continued throughout their lives and resulted in a series of major works. Among them was the ‘The Sidat Sangara: Text, Translation and Glossary (2013)’ with notes on the classic 13th century Sinhala grammar and its commentaries. They worked together on this monumental work of scholarship for nearly three decades. A master South Asian chef, Prof Gair had a Sri Lankan cookbook underway when he passed away. He never recovered from the loss of Prof Karunatillake, who predeceased him in 2012. (Summarised from James Gair’s obituary on the Cornell University South Asia Programme website) |

|