A green weave with a green view

The factory is no longer visible from the road, much as architect Tilak Samarawickrema envisioned in his original plan. Now you can’t see it at all, it’s the way I wanted it, he notes with satisfaction. Shrouded in greenery, it blends in with the hillside in this forested area.

A view of the entrance from the mezzanine floor

The factory, the veteran architect is talking about, which is on the shortlist for the Geoffrey Bawa Awards for Excellence in Architecture 2017 is ‘Mihila’. Built in 2008, it was a ‘green’ factory when ‘green’ was not the buzzword it is today.

Asia’s first carbon neutral apparel factory, it was awarded the LEED Gold Award in 2008 (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design –‘the most widely used green building rating system in the world’) from the US Green Building Council. In 2010, Mihila also received the National Energy Efficiency Award.

When his long-time clients the Hirdramani Group came to Samarawickrema with the invitation to create this ‘green’ factory, for which they were aiming to gain the LEED Gold certification for newly built facilities, he was intrigued. He had done factories before, modern and cutting edge, in his long career but never a ‘green’ factory.

The eight- acre site, 70 km from Colombo was in Agalawatte, a lush hillside, bordered by a rainforest. It was biodiversity rich, had paddyfields scattered around and a wetland which Samarawickrema kept and developed, enlisting the support of IUCN (the World Conservation Union) to work with the Group to document the biodiversity within the factory premises and make recommendations on how the habitat could be sustained.

For the main building, a steel facade was created in front of the gable end that faced the road and root balled trees were introduced within this frame work with plant troughs sitting on top. Solar panels would be an architectural feature in the design.

The solar panels contribute to the energy saving (providing 5% of the factory’s total energy requirements ) and were designed with spaces between to make servicing practical. White-coated zinc aluminum roofing sheets that reflect the sun were used to reduce radiation.

Solar powered street lights that required just four hours of sunlight were also introduced.Amazingly, for a building of this scale housing around 1,500 workers, the Mihila factory has no airconditioning.

Instead an evaporation cooling system which uses only 25% of the energy an A/C system would consume keeps the temperature 4-5 degrees lower than the outside temperature.It also ensures a consistent circulation of fresh air within the factory, Samarawickrema points out.

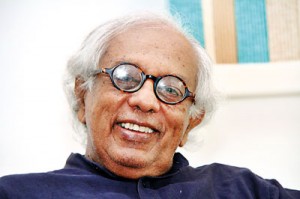

Tilak Samarawickrema

Prismatic skylights were used, providing filtered light cutting down on the fluorescent lamps one sees in factories. 250 W low bay lamps come into play to provide additional lighting when there is inadequate sunlight and the sewing machines have LED lamps fitted for more detailed work.

As the country’s urban areas reel under the weight of a garbage crisis, Mihila’s waste management system is a model that was carefully planned. Solid waste is separated into waste cut, polythene, paper and food waste.

The polythene is recycled, fabric waste which is a considerable 5000 kg a week goes to cottage industries while a piggery in the neighbourhood gets the kitchen waste. Waste water is treated biologically and re-cycled for toilets and gardening and there is also a 100,000 litre tank used for rain water harvesting.

Forming a green screen on the slope in front of the factory is a woodlot for which Samarawickrema chose indigenous trees like Erabadu, Domba, Kottamba, Kumbuk, Jambu and, Suwanda. Taking in the paddy fields that stretched like a cool green carpet around the area, he contemplated having them within the premises but accepted the reality of security needs.

Instead he prevailed upon the Hirdramani management team not to erect a parapet wall that would block the view from the road. “I seduced them with visuals,” he chuckles, putting forward the idea of a chainlink fence and a moat around the property.

The view from the mezzanine floor where the offices and boardroom sit is also a vista of green, just like the view from atop the Warana temple rock in Attangalla, which gave him this inspiration.

Mihila which means ‘earth’ is a model today for Patagonia, the high end outdoor clothing label which the factory supplies. Mihila is also visited by schoolchildren and architecture students who find it a working model of contemporary sustainable design – a green factory that has lowered the carbon footprint by 48%, energy consumption by 48%, water consumption by 70% and that manages waste 100%.

The architect’s sketch of the woodlot in front of the factory

It was a team effort with many consultants involved, says Samarawickrema, mentioning in particular, the contribution made by one of the Hirdramani Group’s directors Arjuna Kuruppu.

For Samarawickrema, whose stellar career has seen him veer from design to art and architecture with equal distinction, it is difficult to pinpoint which brings the greatest satisfaction.

As a young architect fresh from the Moratuwa University, he also interned briefly as an architectural assistant in Geoffrey Bawa’s studio before moving on to work with other leading architects and then spent a golden decade in Italy on a scholarship from the Italian government soaking in the design world of Milan, and Rome in all its richness of art and culture. The artist in him emerged in the line drawings he is famous for.

Back home in the 1990s, he embraced craft design – working with the rural weavers of Thalagune to create tapestries of subtle sophistication that would be exhibited in such rarefied spaces as the Deutsche Textile Museum in Krefeld, Germany and the Norsk Form Design Museum in Oslo.

His tapestries were sold too in New York’s MOMA Design Store. More recently, he has created intricate wire sculptures – delicately suspended, they greet visitors to his airy and elegant Colombo 5 home and studio.

If his art and design have as many have said, been firmly rooted in his Sri Lankan heritage, his architecture throughout has been uncompromisingly modern, as seen in the projects, his firm Tilak Samarawickrema Associates established in 2000 has encompassed – homes, banks, factories.

Ever creative, his quest for new avenues continues. His current project, interestingly is an office interior which transfers the tapestry aesthetic to floor carpeting through the use of carpet tiles!

All green: The Mihila factory with solar panels on top