Art as a Place – The Self as Agency

“Previously there was a lot of blaming the past and being trapped in it,” says Jaffna-based artist and curator T. Shanaathanan. “Now it’s more about self-interrogation.” Speaking on the eighth anniversary of the end of the Sri Lankan civil war, Shanaathanan is discussing the latest phase of art exploring issues largely derived from the conflict.

As we talk through artists working with autobiography and introspection, his recent curatorial project, “Self-Portraits,” (2017) and his contribution to the long-awaited book, “A to Z of Conflict,” it becomes clear that many of these current initiatives reflect less upon victimhood, and more upon ‘the self’ as a form of agency.

Nillanthan, Kingdom (Tamil alphabet ), A to Z of Conflict, 2017. Courtesy the artist and Raking Leaves

For example, one of the artists from “Self-Portraits,” Jasmine Nilani Joseph, tells us the story of how her family had to leave their home in Vasavillan, near Jaffna, when she was just 45 days old.

“The house is no longer there, but the key is still waiting under the land,” she begins. Before leaving their village, which had been designated as a high-security zone, her parents buried the key to their home in the hope that they would return someday – once the conflict was over.

In reality, Joseph and her family were to face repeated displacement, and it was only last year, a full 26 years later, that they were able to go back and visit the spot where their house once stood.

Today, a young and astute art graduate from the University of Jaffna, Joseph’s delicate drawings contain within them moments and junctures that have inevitably shaped her psyche. Her recent series “Fence” (2016-ongoing) exemplifies this, as it speaks to wider “structures of violence,” but also illustrates particular experiences from her life; including the secret key which remains hidden underground.

Joseph is not alone in her approach. Artists P. Pushpakanthanan and M. Vijitharan, who also graduated from the University of Jaffna often depict traumatic moments that they witnessed during the war in their art, working with such memories in constructive ways.

We are told by psychologists such as Elisabeth Pacherie that self-discovery is essential to developing a sense of self-agency. As part of mentoring these young Jaffna-based artists, Shanaathanan asks them to think about how they position themselves within any residual issues.

“Without understanding yourself, understanding the other is not possible,” he explains. This may be the case, but with much of this early, so-called, post-conflict art being produced out of Jaffna, and shown in Colombo – the dynamic of the ‘self’ and the ‘other’ becomes even more apparent. Shanaathanan is only too aware of this “[In Colombo] their counter-self becomes clear,” he says.

The meeting of the self and other, in philosophical terms, is said to lead to beginning of self-consciousness. In reality, it may be far too early to judge just how this current dynamic will affect the way post-conflict art goes on to be produced and consumed in Sri Lanka.

For now, Shanaathanan consciously negotiates such shifts and phases through exhibitions like “Self-Portraits,” but also works on a number of longer-term post-educational, curatorial and archival initiatives.

Programmes at the Sri Lanka Archive of Contemporary Art, Architecture & Design in Jaffna, for example, which he co-directs with curator Sharmini Pereira, often take the long view.

When we meet in May, Pereira is in the process of developing one of the most comprehensive projects to look at the context of the war to date – looking at the very source of the conflict, to its remaining residues.

Five years in the making, the encyclopedic tome “A to Z of Conflict,” is due to be published by her non-profit publishing outfit, Raking Leaves, later this year, and takes a more macroscopic perspective than previous projects.

The book encompasses nine contemporary artists from Sri Lanka and its diaspora responding to the letters of the English, Sinhala and Tamil alphabet (548 in total) by associating a word with it, and then creating an accompanying image.

Looking through a preview of “A to Z of Conflict” reveals that it serves as a type of testament to the idiosyncrasies of ethno-linguistic conflict, seeking to ask fundamental questions about the very ideas embedded in language.

What are the potential meanings behind different symbols? How do these get altered in divisive social contexts? As Pereira says, “Language is not just what we speak.

We’re framed by it. We’re socialized by it.” Expanding on this sentiment, we’re reminded that language is also key to the notion of constructing the self. Reflecting upon such deep-seated dynamics, the book will provide a kind of psycho-social mapping of the civil war.

As one of the contributing artists, Shanaathanan feels that the project has given him a chance to see things from a different point of view and to look at the bigger picture. For example, as an English and Tamil-speaker, Shanaathanan realized that most of the words he knew in Sinhala were those used by soldiers at checkpoints; go, come, enough; open, bag, show, identity.

Rather than focus on their traumatic associations, however, he tells us that he used the interrelation between letter, language and image to “really play” with meaning and instead create “critical, satirical and light” readings of the words; something he does not normally do in his art practice.

Many of the other contributing artists also focused on words which came into existence, or acquired new meanings during the conflict, making us reconsider how we identify with them.

When we met in Jaffna last year, artist, poet and political columnist Nilanthan talked of how he felt certain personal and political ideologies had had their meaning distorted during the war.

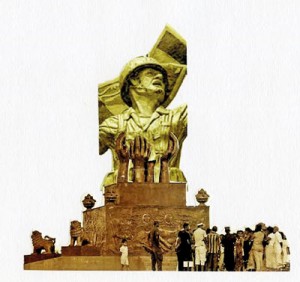

For the “A to Z of Conflict,” Nilanthan spliced together media and satellite images to create powerful collages, including those of displaced people in front of a mock-monument in “Kingdom (Tamil alphabet)” (2017) and refugee camps by the sea in “Seaside (Tamil alphabet)” (2017).

Rather than using the language of the victim, Nilanthan explained that writing and painting has helped him to work through his personal experience of pain and grief.

Shanaathanan too speaks of how such art projects can act as both a form of knowledge production and agency. In cases where the self is a source of agency, artists are often looking to reconfigure subjectivities or identities.

For photographer and documentary filmmaker Anomaa Rajakaruna, however, working with Tamil, Sinhala and English may also allow for the construction of multiple selves. She explains how moving across geographical borders and linguistic barriers is reflected in her work.

“I’m interested in what it means to not be bound by one language or one perspective” she says. As part of her contribution to the book, Rajakaruna looked at how the meaning of a word may change, just by the shifting of one letter.

For example, in the black-and-white photograph “Warship/Worship (English alphabet)” (2017), we see a striking image of a military tank, placed intentionally at Elephant Pass (referred to as ‘the gateway to the North’) by the army after the war.

Rajakaruna observed how this symbol of victory (or loss, depending on one’s view) came to acquire a revered status, being worshipped by visitors with garlands of flowers and tied flags.

Rajakaruna tells us that this photograph is part of her longstanding series tracking Sri Lanka’s changing landscape, in which she captures details of its “wounds, marks, monuments and symbols.”

While some artists in Sri Lanka talk of wanting to move on, or away, from the war, Rajakaruna reminds us of the continued and critical significance of engaging with it as a subject. “The war may have come to an end, but the conflict did not,” she says.

“We’re still living with many conflicts. In this transitional time, it is important that we address issues and raise questions as a way of moving forward. It’s about looking for justice, yes, but it’s more about healing.”

Shanaathanan agrees that the unearthing of these narratives serves as a shared solution for all. “I wouldn’t say [such projects] are about the past. They negotiate with the past in order to come out of it.

But it’s part of you. It’s part of the future.” Thinking of the “A to Z of Conflict” as an open and accessible monument may be useful, however, it is also its individual and nuanced narratives which give the project its heft.

Whether it be such momentous mappings, or more ephemeral exhibitions, what may ultimately underscore their continued relevance is the idea that memory, association and play allow for the production of multiple, reconstructed and agentive selves.

* Art as a Place derives its name from the Sarai Reader 09 exhibition (2013) in New Delhi, curated by Raqs Media Collective