Getting to know titbits of memorable artistes

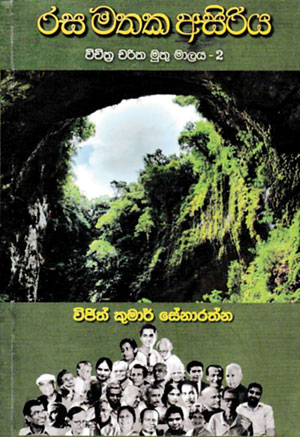

View(s): Reading about people’s talents, those in different vocations, professions and numerous other fields is always fascinating. Some may be well known personalities, others may not be so well known. Yet, the writer can always make the narrations interesting. That’s exactly what Vijith Kumar Senaratne has done in ‘Rasa Mathaka Asiriya’ – a compilation of biographical sketches done for a couple of newspapers.

Reading about people’s talents, those in different vocations, professions and numerous other fields is always fascinating. Some may be well known personalities, others may not be so well known. Yet, the writer can always make the narrations interesting. That’s exactly what Vijith Kumar Senaratne has done in ‘Rasa Mathaka Asiriya’ – a compilation of biographical sketches done for a couple of newspapers.

Reading through the book, I started recalling some of the characters who are no more but whose talent still reverberates in the mind. Ace comedian Samuel Rodrigo passed away nearly two decades back. But seldom can we forget Amaris Aiya – the character he played over the radio in an era when there was no television in Sri Lanka. His sarcasm, serious tones, ability to imitate VIPs are all still fresh in our minds. Vijith interviews his wife and gets an insight of the artist. She relates anecdotes and incidents.

Once Samuel and others who performed in H.D. Wijedasa’s‘Vihilu Thahalu’where Prime Minister Kotelawela was imitated were summoned to Kandawela, Sir John’s home. He had got down the tape and sat and listened to it along with the performers. At the end Sir John had laughed to his heart’s content. ‘Superb,’ he said, and ordered a repetition. When they had acted eating ‘kiribath’ with the fork imitating Prime Minister Bandaranaike (he had a weekly gathering of media men for a ‘kiribath’ breakfast at his Rosmead Place residence), a third party had got offended and got the programme banned. Protests by the listeners forced the authorities to start a similar programme. Alfred Perera’s‘Vinoda Samaya’ thus replaced ‘Vihilu Thahalu’.

It’s not often that film producers get interviewed. It’s always the director. Vijith picks Chitra Balasuriya who produced two classy films – ‘Parasathu Mal’ directed by Gamini Fonseka and ‘Mahagama Sekera’s‘Thun Mang Handiya’. Hailing from Gampaha, Chitra was a young man with determination and courage. He started his career as a photographer in Central Studio in his hometown. In 1954 he opened his own ‘Chitra Studio’ which soon became the meeting place of artistes. Pandit Amaradeva used to come to Gampaha often by train to meet his tailor. Sekera who wrote lyrics for Amaradeva’s songs, came from Radawana, his native place to Gampha Lorenz College to learn English. Musician Lionel Algama from Gampaha was a music teacher. Dramatist Dayananda Gunawardena also stayed at Gampaha.

When he thought of making a film, Chitra met talented script writer of ‘Kurulu Bedda’, P.K.D. Seneviratne who gave him a script in two weeks. Chitra then met Lester James Peries who had by then completed ‘Gamperaliya’. Since Anton Wickremasinghe was keen to produce another film with Lester, the latter suggested Gamini Fonseka handle the film and promised any assistance needed. Filming ‘Parasathu Mal’ began.

Chitra relates how he used to drive from Gampaha to Kolonnawa to pick up veteran actor D.R. Nanayakkara. “There was a tap on the road opposite his house. He used to squat under it with difficulty and have a quick bath laughing away. He never bothered that I was waiting for him. He took his own time and he always got into the car uttering ‘Fantastic water’.”

Throughout the book, the reader can enjoy such ‘hidden tales’ that Vijith had cleverly got the interviewee to come out with. In all, the book covers 33 personalities, most of them from different artistic fields. Vijith, a follower of the Cumaratunga Munidasa school, uses a simple readable style of writing. He also uses direct quotes, thus adding authenticity.

His narration on Latha Walpola, veteran Sinhala songstress, takes the form of a tribute on her completing 50 years in her career. That was in 2003. He outlines her contribution to the music scene from the time she sang ‘NamoMariyani’ when she was 13. Named Rita Genevieve Fernando, the close resemblance of her voice to Lata Mangeshkar’s made the renowned musician Susil Premaratne change her name to Latha. He trained her to change her singing style from church hymns to a more melodious rhythmic style. He sang the popular numbers ‘Kalu kelaninadee’ and ‘Ranvankaralinpesila’ amidst others with her. She started playback singing in films with ‘Eda Re’ (1952) directed by Shanthi Kumar.

Vijith mentions how Latha recalled the way she and her husband, Dharmadasa Walpola had to fight their way through to break the practice of Indian singers virtually forcing themselves to sing Sinhala sings. Of course, that was the time that Indian filmmakers had a big say in the Sinhala cinema

He quotes Latha’s thoughts about the prevalent ‘geethamangkollaya’ (song robbery). She says: “If the doctors or nurses have problems they strike. If a bus conductor is found fault with, their entire fraternity protest. If there is a problem with a bus driver, all drivers stop work. Even if ten artistes are killed, there is no one to do anything. Who rose up when an artiste’s hair was forcibly cropped? Recently someone else was beaten…who took any action? Artistes prefer to mind their own business. There is no unity among them. Artistes have to seek protection on their own. No one looks after those who are helpless.”

This is just a brief review of Vijith’s effort. ‘Rasa Mathaka Asiriya’ has to be read in full to savour the contributions made by the 30+ personalities in their respective fields.

D.C. Ranatunga