News

Bug vs bug

A ‘harmless’ little bug to battle a ‘harmful’ bug!This is the technique that Australia is offering Sri Lanka, caught in the vice-like grip of a dengue epidemic in the past seven months which has seen more than 100,000 men, women and children falling ill, with 290 deaths.

Prof. Scott O’Neill during the interview with the Sunday Times Pic by M.A. Pushpa kumara

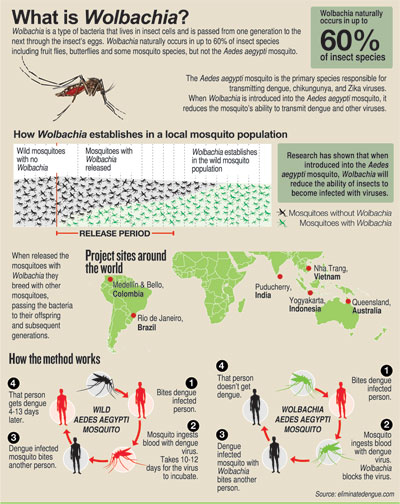

The harmless, naturally-occurring bug or microbe is the bacterium Wolbachia which has successfully been used to block the virus spreading dengue. The added bonus from Wolbachia is that it is also effective in curbing Zika and chikungunya.

With Letters of Intent being exchanged by the Australian and Sri Lankan governments on Wednesday, the details of the project have to be scoped out, the Sunday Times learns.

Wolbachia is not an immediate solution to the current dengue epidemic but a long-term one in combating the dengue virus, says the Director of the Institute of Vector-borne Diseases of the Monash University in Melbourne, Prof. Scott O’Neill in an exclusive interview with the Sunday Times.

Prof. O’Neill is also Director of the university’s ‘Eliminate Dengue Program’ which has been conducting groundbreaking research. Under this international research collaboration which aims to reduce the global burden of mosquito-borne diseases, his team is implementing a sustainable control method using Wolbachia to reduce the ability of the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes to transmit harmful viruses. The method has already been tried out successfully in Australia and is now being used in other countries including India.

Before getting down to the science, Prof. O’Neill comes up with the image of someone who is “really sick” with dengue, having a piercing headache, body aches and pains and a rash. But just because someone else is in the same room, this person will not get the virus, even if the ill-person is bitten by a dengue-spreading mosquito, after which it bites the other person.

“It takes a while for the virus which the mosquito gets from the infected person to grow in its body, to be ready for transmission to another person with another bite. If the environment is hot, the virus grows faster. Typically it takes about 8-10 days for the virus to grow within the mosquito’s body and that means that the mosquito has to live quite a long time,” he says.

Next he ‘profiles’ the main vector of dengue, Aedes aegypti, as an “exquisite” adapter to do what it has to do, bite only humans. It is the female mosquito that bites humans as it needs the protein found in human blood to produce eggs. “It is a ‘sneaky’ mosquito which won’t sit on your arm for a long while to be squashed. If you move a little bit, it will fly away and await another chance for a bite. It changes its behaviour and thus becomes a fantastic vector for the transmission of disease.”

Quoting a colleague, he likens Aedes aegypti to the ‘cockroach’ of all mosquitoes due to its preference to hide and take bites when the conditions are suitable.

When asked about Aedes albopictus, this scientist who has studied mosquitoes his “whole life” is quick to point out that when looking at evidence, it is an “unimportant” vector in the spread of dengue and usually epidemics are set off by Aedes aegypti which “just loves people”.

Looking at the modus operandi of Wolbachia, meanwhile, Prof. O’Neill picks up the fact that this bacterium commonly found in 40-60% of insects stops the dengue virus from growing within the body of the mosquito, making it reach a ‘dead-end’, thus stopping dengue transmission. But Aedes aegypti does not have this bacterium, but what does have it are “just about” most insects such as other mosquitoes, honey-bees, butterflies and fruit-flies .

Every country has this naturally-occurring bacterium which has a very broad distribution, he says, leading us through our mind’s eye to our homes and making us visualize a bowl of fruit with over-ripe bananas which give out a strong odour. This attracts a small fly with red eyes, which is Drosophila. This is the insect from which they extracted Wolbachia, which was, however, a long and hard process.

“It took us 10 years,” says Prof. O’Neill, stressing that it was the “key technical roadblock” that had to be overcome. Once extracted though, Wolbachia was introduced to the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in the laboratory. Thereafter, these mosquitoes were released into the wild. They then bred with mosquitoes in the wild and gradually the Wolbachia was passed on from generation to generation through the mosquitoes’ ovaries.

The Sunday Times learns that perfecting the technique of infecting the mosquitoes with Wolbachia took a long time as it involved using microscopic needles to take the microbes from the fruit-fly and insert it into young mosquito eggs. The expertise needed was how to do so without bursting and destroying the eggs. The next challenge was to make the Wolbachia sustainable to last down the generations in a host (mosquito) different to its original one (fruit-fly). The team overcame that by “conditioning” the Wolbachia, extracted from the fruit-fly, by growing it in mosquito cell-lines.

This is recent history now and Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes have been let loose and tried and tested by scientists at the ‘Eliminate Dengue Program’ in their own backyard. Prof. O’Neill details the trials conducted in Queensland in 2011, before they showed the world the dengue-fighting potential of Wolbachia.

The proof has come out strongly. Six years after the first mosquito-releases in Cairns, Queensland, with sustained high levels of Wolbachia, there is no evidence of local dengue transmission in the release areas.

After deployment of Wolbachia, a rapid decline in local disease transmission is expected, but variables such as seasonality, size of the release area, speed of Wolbachia establishment, importation of cases and quality of surveillance data can mean that it might takes six months or longer to register the impact, it is understood.

Even though Wolbachia stops local transmission, the danger of a spread of dengue could arise from imported cases and this is why countries deploying Wolbachia are being encouraged to take the usual prevention measures.

| People’s involvement essential for programme to work There is no profit involved when Monash University’s ‘Eliminate Dengue Program’ is shared with Sri Lanka’s Health Ministry, it is learnt. Prof. Scott O’Neill states that the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended a pilot deployment of Wolbachia and the programme is in the planning stage now. People’s involvement is essential, as it needs “to be picked up locally”, he reiterates and explains how they went from house-to-house creating awareness in other countries including their own before the deployment of Wolbachia. Initially, after all permits and requirements are met, a colony of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes ‘armed’ with Wolbachia will be sent to Sri Lanka from Australia and deployed into a selected area, to mix with the wild mosquito population there. Gradually, over a period of time, there will be back-crossing leading to Wolbachia being passed on to all the Sri Lankan mosquitoes in that area. After about six generations, the DNA specific to the Australian mosquitoes will disappear. A note from the Australian High Commission, meanwhile, gives the details of the link-up where the Australian Government will help combat dengue fever, by partnering with the WHO, Monash University’s Eliminate Dengue Program and Sri Lanka’s Health Ministry. The WHO is to be given a Rs. 58 million grant to immediately implement intensive dengue prevention and control measures. Working with Sri Lankan health authorities and other partners, the objective will be to reduce transmission of dengue and thereby the incidence by more than 50% over 4-6 weeks in high-risk districts. For this to be achieved, strengthened surveillance, spatial mapping and analyses of health data, community awareness and action and continued vector control measures will be coordinated and intensified. Prevention and control measures will need to be sustained to mitigate the risk of an outbreak of this magnitude again, the note said. Monash University’s Eliminate Dengue Program is to be extended a Rs. 116 million grant from Australia’s InnovationXchange for a research partnership with the Health Ministry’ Dengue Control Unit, headed by Dr. Hasitha Tissera, to trial the introduction of Wolbachia to Sri Lankan mosquito populations. | |