Sunday Times 2

Government holds the key to the nation’s memory

Even though apartheid-era bureaucrats destroyed much of South Africa’s records in an attempt to sanitise history, much survived and these have to be opened to public scrutiny in the interests of accountability. It is true that our experience of the present depends upon our knowledge of the past. Czech-born writer Milan Kundera, who at different times of his life was a supporter and critic of the Soviet Union’s Communist Party, famously wrote: “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.”

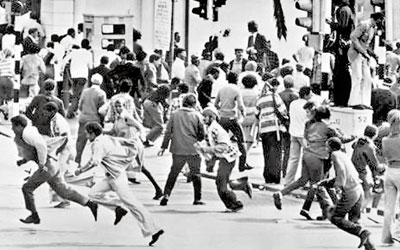

Anti-apartheid activists running away from a police charge during a demonstration in 1976 in Cape Town. AFP

The opening of secret files in East Berlin and elsewhere in the former eastern bloc caused splinters after the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall. Kundera himself had to refute accusations that he betrayed a spy in communist Czechoslovakia. But transparency and the disclosure of the regime’s ugliness became a vital part of reconciliation and healing.

In South Africa, apartheid-era records were famously trucked to furnaces where they were incinerated to prevent them falling into the hands of the new administration. The deliberate destruction was a way for government to rid itself of incriminating evidence of the torture, forced disappearances, spies and corrupt practices that should have been part of the nation’s memory.

By destroying records, apartheid bureaucrats hoped to sanitise history and shield those implicated from accountability. Yet not everything was destroyed. A recent colloquium to promote transparency of public records threw light on the records that survived. Cabinet minutes, state security documents, defence archives and even military records weren’t included in the apartheid state’s purge.

But for researchers hoping to pry open these files, the door has most often been shut in their faces. In fact, it appears the democratic government has shielded apartheid crimes from the public, reinforcing the very same secrecy that apartheid thrived upon. The post-apartheid departments of justice and defence in particular have worked to protect apartheid henchmen by withholding the key to their histories.

Hennie van Vuuren, director of Open Secrets and author of Apartheid Guns and Money – A Tale of Profit, says the department of defence recently withheld at least 400 boxes of documents requested by his nonprofit organisation. The material would have shed light on the sanctions-busting activities of Israel and China. Open Secrets will be forced to mount a court challenge to gain access to the material.

If apartheid is, among other things, the story of the elimination of voices that should have been part of the nation’s memory, the archives hold the power to look back.

Officials in military intelligence were prepared to release some apartheid-era documents to Van Vuuren, but Armscor, which houses its archive in the same building, eventually provided him with material – except, it had been so heavily redacted it was incomprehensible. The reason may lie in revelations in Van Vuuren’s book. He says Armscor used 844 bank accounts in 196 countries to move money around the globe to bust sanctions.

Safeguarding history

Speaking at the same colloquium, former intelligence minister Ronnie Kasrils called on the government to release apartheid-era archives. He said apartheid-era informers from within the African National Congres also need to be exposed. A list of these people had been handed to former president Nelson Mandela, he added.

“In the context of the time, Mandela was really focused on maintaining the stability, a unity within the liberation movement … opening that list could be regarded as opening a can of worms,” Kasrils said. Foundation for Human Rights chair Yasmin Sooka said opening the apartheid archives will yield information about activists who were imprisoned and tortured under apartheid – and those, such as Ahmed Timol, who died.

Timol’s death is the subject of a reopened inquest. The original inquiry’s findings in 1972 said the anti-apartheid activist committed suicide by jumping out of a window of the 10th floor of John Vorster Square police station. Closing arguments were heard last week.

Sooka said the inquest reinforces the importance of securing the archives. Over its 19 days, titbits from police files made their way into the public domain for the first time.

This new information, in the form of the testimony of policemen and fresh evidence, has revealed patterns in the names of officers involved in torture and detention, she said. It has links, for example, to the case of Neil Aggett, which the foundation hopes to pursue next. Aggett, a doctor and trade unionist, died at John Vorster Square in 1982 after 70 days in detention. The police said he hung himself.

Sooka said elements of the South Africa state still have an “intelligence mind-set”. Sharing the sentiments of Van Vuuren, she added that these elements want to maintain secrecy. Other organisations have also sought access to secret documents. The South Africa History Archive recently took to the courts to compel the Reserve Bank to release records of suspected apartheid-era financial crime.

In 2014 the archive requested bank records that would reveal evidence of fraud — including manipulation of foreign exchange, the forging of Eskom bonds and sanctions busting.

The request relates to Vito Roberto Palazzolo, Jan Blaauw and Robert Oliver Hill.

But the bank denied the archive’s request, citing confidentiality and the possible risk to South Africa’s economic interests. Its “blanket refusal” to release the material is not fitting for a democratic state, advocate Geoff Budlender said in court.

Given the apartheid government’s obsession with secrecy, this is all the more outrageous.

Managing memory

For better and more transparent management of apartheid archives, South Africa may want to consider the East German experience. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Germany opened access to all the material of the eastern bloc’s state security service from 1945 until 1990. More recently, some of that archive has also been made available online.

The German government employs 2,500 people to manage the archive, according to the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s Gerd-Rüdiger Stephan.

While present-day archives don’t face the threat of apartheid’s systematic destruction, a different set of challenges is becoming evident. Some material has been destroyed or lost because of the shortage of space and the absence – and inadequate funding – of archive management.

Elizabeth Mbatha, head of archives for the Gauteng province, said the National Archives of South Africa in Pretoria has run out of space. It cannot accommodate more records, which leaves some of the responsibility for administering material with provincial authorities.

However, the act governing it stipulates that the National Archives is the only authority that can catalogue local records. This means documents at magistrates’ courts and police stations around SA are in danger of being lost because there is no home for them.

The hands of provinces are tied. Mbatha, speaking on behalf of one branch of government, made an appeal to civil society to lobby another branch of government to change the law so these records wouldn’t be lost.

There are other risks. Writer John Matisonn, who began his career in journalism at the Rand Daily Mail in the 1970s, said portions of the newspaper’s archive, handed to the University of Johannesburg for safekeeping, were incinerated a few years ago because worms had been found crawling through the heavy tomes.

The overwhelming share of the United Nation’s anti-apartheid work relied on information from the archives of the Rand Daily Mail, Matisonn said. The African National Congres probably relied on the same archive for much of its information at a time when censorship, banning, incarceration and confiscation of material made it difficult for activists to stay abreast of state action.

The internet could change all that. US-based company NewsBank has digitised the entire Rand Daily Mail archive, and will make it available for a fee.

This is a reassuring development. For if apartheid is, among other things, the story of the elimination of voices that should have been part of the nation’s memory, the archives hold the power to look back. The business deals signed behind closed doors, the hushed voices of enablers and the crushed struggles of resisters give us clues that build the recovery of memory, which will help us reconstruct and come to terms with the past.

Courtesy www.businesslivewire.co.za