In an ‘unsung office’ a new dictionary is in the making

Ever wondered what goes on within the colonial building of the Sinhala Dictionary Office on Sir Marcus Fernando Mawatha, opposite the Colombo National Museum? Once the auditorium of the adjacent Archaeology Department, this ‘arched and pillared’ structure reflecting a flavour of an era gone by, lends space to the painstaking task of compiling and revising the Sinhala-Sinhala Etymological Dictionary and Sinhala-English Dictionary. The office which comes under the Department of Cultural Affairs is responsible for the only state-supported dictionary in the country.

Ever wondered what goes on within the colonial building of the Sinhala Dictionary Office on Sir Marcus Fernando Mawatha, opposite the Colombo National Museum? Once the auditorium of the adjacent Archaeology Department, this ‘arched and pillared’ structure reflecting a flavour of an era gone by, lends space to the painstaking task of compiling and revising the Sinhala-Sinhala Etymological Dictionary and Sinhala-English Dictionary. The office which comes under the Department of Cultural Affairs is responsible for the only state-supported dictionary in the country.

The journey of the Sinhala Dictionary Office which marks its 90th year is an eventful one, shifting its quarters from several places to its present shelter in 1971. This largely ‘unsung office’ made double history this year with the appointment of its first woman Editor-in-Chief, Prof. Rohini Paranavitana. One-time Head of the Sinhala Department, University of Colombo, Prof. Paranavitana brings with her a wealth of experience. She succeeded Prof. Ananda Abeysiriwardena.

“When all my bright counterparts chose to do Science at Visakha Vidyalaya, I became the exception opting for the Arts stream,” smiles the scholar who rose from a junior lecturer of Sinhala at Peradeniya to head the Department at the Colombo University. Her love for all things Oriental, drove her to read Sinhala, Sanskrit and Pali for her degree at Peradeniya. In an era where liberal arts were scoffed at, young Rohini’s family, particularly her mother fuelled her passion. Well known historian Prof. K.D. Paranavitana also encouraged her literary pursuits.

Carrying forward the legacy of her illustrious predecessors such as Sir D.B. Jayatilaka, Prof. M.D. Ratnasuriya and Julius de Lanerolle, Dr. B.F. Wijeratne, Prof. D.E. Hettiarachchi, Prof. D.J. Wijayaratne, Dr. P.B. Sannasgala, Prof. Wimal Balagalle and Prof. Vinnie Vitharana, Prof. Paranavitana is ambitious to make this historically and culturally significant compilation a ‘household’ item and ‘digitally accessible.’ The effort behind a dictionary is colossal. Thousands of books and historical sources are perused to compile this ‘one-stop-shop’ of a compilation. Each word is lent an ‘index card’ which elucidates its meaning, etymologies and grammatical constructions. The exercise is supported by an editorial team together with an advisory board of religious, ethnic and cultural diversity.

Carrying forward the legacy of her illustrious predecessors such as Sir D.B. Jayatilaka, Prof. M.D. Ratnasuriya and Julius de Lanerolle, Dr. B.F. Wijeratne, Prof. D.E. Hettiarachchi, Prof. D.J. Wijayaratne, Dr. P.B. Sannasgala, Prof. Wimal Balagalle and Prof. Vinnie Vitharana, Prof. Paranavitana is ambitious to make this historically and culturally significant compilation a ‘household’ item and ‘digitally accessible.’ The effort behind a dictionary is colossal. Thousands of books and historical sources are perused to compile this ‘one-stop-shop’ of a compilation. Each word is lent an ‘index card’ which elucidates its meaning, etymologies and grammatical constructions. The exercise is supported by an editorial team together with an advisory board of religious, ethnic and cultural diversity.

What sets this dictionary apart from other dictionaries is its effort to elucidate the meanings of words, their etymologies and understanding the grammatical constructions. It is also not bound by any individual scholarly genre, explains Prof. Paranavitana. The dictionary mirrors the history of words and the jargon to which each word belongs- for instance, whether a word belongs to medical/clinical or any other jargon. A dictionary of this nature also revives certain words and phrases that make this usable in a contemporary context, says its Chief Editor.

The attempts to compile dictionaries are not new to the Sinhala language, explains Prof. Paranavitana who cites compilations in the glossary style such as that of Dampiya atuwa geta padaya , in which Pali words were rendered Sinhala meanings. Several dictionaries written in alphabetical order by scholars such as Attaragama Rajaguru Bandara, Veragama Punchi Bandara and Ven. Boruggamuve Revata Thera are found in the history of lexicographical works. However, they are not comprehensive and complete dictionaries.

Laborious work: Prof. Rohini Paranavitana at a meeting with staff. Pix by Indika Handuwala

The idea of a dictionary to facilitate better administration over the colonized, was also mooted by the colonial masters, dating back to the Portuguese rule. “In 2005 when I visited the Geographical Society in Portugal, I found a Sinhala-Portuguese hand-written dictionary in which the word ‘thimble’ is offered the Sinhala meanings of didal (which is more in tune with Portuguese flavour) and mudu hiruwa,” recollects Prof. Paranavitana with a smile. The foundation for a modern and a scientific compilation, however, was laid by the British scholars such as Rev. Benjamin Clough, Rev. Charles Carter and John Callaway, she says.

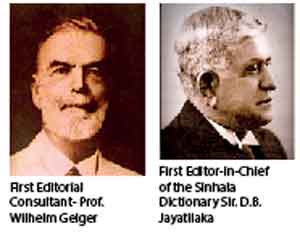

With the inauguration of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society in 1845 the study of Sinhala language and literature was revived. Scholars- both local and foreign, lobbied for a comprehensive Sinhala Dictionary. Following a series of committees, reports and recommendations, it was only in 1927 that the project took wings under the auspice of the eminent linguist Prof. Wilhelm Geiger who was appointed Consultant and Director of the Editorial Board. The exercise was further given muscle by Sir D.B. Jayatilaka as its first Editor-in-Chief. It was only in 1992 the Sinhala-Sinhala Etymological Dictionary with its 13687 pages was completed. The job of a dictionary compiling team, however, never ends as new words are added from time to time. The revised editions incorporate such changes and to date five revised volumes have been published.

The Sinhala Dictionary has traversed diverse eras from that of the typewriter, the computer and to the digital era. A concise Sinhala dictionary is also in the pipeline for wider usage, especially in schools, offices and homes. “The original Sinhala Dictionary has its practical limitations for everyday use, hence a concise dictionary of the same is urgently felt,” says the Editor who is ambitious in taking it to the public domain, especially schools. The Sinhala- English Dictionary which is being prepared has completed 27 volumes so far and a Tri- lingual Dictionary of Sinhala – English – Tamil is also being prepared. Enabling an online version is also a need of the hour, for which ground work is being done, says Prof. Paranavitana.