News

Prices rise, farmers and consumers suffer in middlemen’s tyranny

The already high vegetable and fruit prices are expected to rise further during the upcoming festive season, but farmers say their products could be sold at affordable prices if measures are in place to rein in middlemen and traders making undue profits.

The Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research and Training Institute’s Agri-Business Division Head, Duminda Priyadarshana, said vegetable prices were expected to increase by 40-50 in November and December. This was because production would be low during these months with farmers ploughing their land for the next Maha season, while the demand would be high due to the festive season.

But farmers said prices in the retail market were nearly double the prices at which their produce are bought by middlemen.

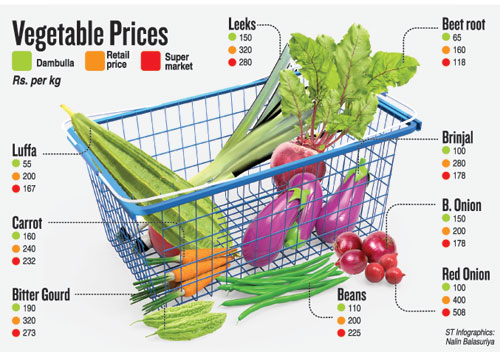

A farmer is paid Rs. 115 for a kilogram of carrot by the middlemen. At the Dambulla wholesale market, it is sold at Rs 160 a kilo, at the Pettah Manning market at Rs. 220 and at the Maradana retail market at Rs. 240.

The price of a kilogram of beetroot at the Dambulla wholesale market was Rs 65 on Friday, while the retail price at the Maradana market was Rs 160. A leading supermarket which buys directly from farmers sells beetroot at Rs 118 a kilogram.

Becoming increasingly unaffordable for the ordinary people is the price of big onions. A kilogram of big onions is sold at Rs. 250 in many retail markets in Colombo and suburbs, though its price at the Dambulla wholesale market was Rs. 100 on Friday.

Up up and away: Vegetable prices to further increase. Pix by Sameera Wickramaarachchi and Kandhana Kumara Ariyadasa

The prolonged drought in the Northern, North-Western, North-Central and in parts of the Southern Province is also another reason for the heavy prices.

In Jaffna, the retail price of a kilogram of big onions is Rs. 500, bitter gourd Rs. 500 and brinjals Rs. 250.

A farmer said they pay commissions ranging from 50 cents to Rs 10 for a kilogram of their produce to middlemen who coordinate with the wholesale businessmen.

“The middlemen receive thousands of kilograms of vegetable and fruits every day. They make huge profits from commissions, virtually doing nothing,” W.M. Gunawardena, who heads the Welimada Uva Paranagama Farmers Association, said.

He said the wholesale businessmen were in cahoots with the middlemen and therefore, they would not buy directly from the farmers.

Mr. Gunawardena said it was the wholesale businessmen at economic centres who determined the price paid to the farmer and the price at which the produce was sold to the retail trader. There was no state involvement and there was no market forces – it was a big racket, he said.

“Wholesale businessmen collude to project a low demand for the farmers’ produce so that they can buy them at low prices. They know the farmers will not take home their vegetables because if they cannot sell them, soon they will rot,” the farmer leader said.

Mr Gunawardana called for the Government’s intervention to set up cold storage facilities so that the exploitation could be curtailed to some extent.

All-Island Farmers Federation national organiser Namal Karunaratne said middlemen and millers were making undue profits also from paddy farmers.

He said that millers bought paddy at low prices from farmers and stored it to be released to the market at a higher price when the demand was high

“The local rice now being sold at Rs. 90 a kilogram was made from the paddy bought from farmers at prices between Rs 28 and Rs. 35 some18 months ago,” he claimed.

Farmers charged that some middlemen manipulated the market by buying and hoarding their produce. They would create an artificial scarcity to sell the hoarded items at a higher price.

Sunil Ranaweera, president of the Dambulla Combined Farmers Foundation, said that some middlemen would go to farmlands directly and offer a price to reap the harvest by themselves. “Farmers are also satisfied as they do not have to incur extra expenses for harvesting. But what happens is the middlemen by delaying the reaping of the harvest create an artificial scarcity for the produce, so they can sell them at higher prices and make large profits,” he said.

Mr Ranaweera said some of traders would give loans to farmers to start cultivation, so that they could buy the produce at low prices.

M. Somawathi (63), a retired teacher from Welimada, said farmers in her area were disheartened and reluctant to engage in agriculture because they could see the middlemen making huge profits while they got only a pittance.

Niluka Kusumkumari (38) said middlemen would even take the polos (young jak fruit) from them without paying anything but would sell it at Rs 40 a kilogram.

She also said the Government should intervene to check unfair business practices.

Aruna Shantha Hettiarachchi, secretary of the Nuwara Eliya Traders Association, said prices could increase by more than 40 percent when items changed hands from the wholesale trader to the retail trader. He said retail traders had to keep this huge margin because 10-15 percent of what they bought would have to be thrown away.

He said he believed the Government should introduce a price-control system to regulate the vegetable market. If a proper cultivation plan was in place and steps were taken to minimise waste, then consumers will be able to buy vegetable at affordable prices, he said.

Dismissing the charges against the middlemen as baseless was I.G. Wijenanda, a former secretary of the Dambulla Traders Association. He said no farmer was ripped off at the wholesale market.

Industry and Commerce Ministry Secretary Ranjith Asoka said the ministry had no plans to control the intervention of middlemen in the market. He said, however, the Government was taking speedy measures to control the cost of living.

Consumers also said they believed if middlemen were done away with, vegetables could be bought at affordable prices.

Meanwhile, in countries like Bangladesh tech-savvy and enterprising youth have created e-commerce platforms aimed at helping farmers get a fair price for their produce and also to give consumers the opportunity to buy fresh food items at affordable prices.