Visiting the ancestral village of a Kandyan freedom fighter

The faded frescoes in the shrine room of Veluwanaramaya

The Chief continued to repeat some Pali verses and while he was so employed, the executioners struck him on the back of his neck with a short sword. At that moment, he breathed out the word ‘Arahan’. A second stroke deprived him of life and he fell to the ground- a corpse. His head, being separated from the body, it was (in accordance with Kandyan custom) placed on his breast.’ The last moments of Moneravila Keppetipola Disava- the first architect of our freedom from colonial manacles, are thus recorded by Henry Marshall, who came to Ceylon in 1808 as Deputy Inspector-General of Army Hospitals in his ‘Description of the Island and its Inhabitants’.

Upon the capture of Keppetipola Disava along with Pilimatalawe on October 28, 1818, Governor Brownrigg was so pleased with the news that he ordered an extra allowance to members of the British Army and in a Gazette notification felicitated Lieutenant O’Neill ‘on the capture of these superlative disturbers of public peace’. The fearless warrior who even instructed the executioner where to strike the second blow so that he would be spared of a third, while chanting gatha, baffled the British who took his skull to the Museum of the Phrenological Society of Edinburgh to determine what rendered him incomprehensible courage.

A Keppetipola heirloom

The skull which was returned to Sri Lanka after yet another battle waged by the Keppetipola descendants, was transported on a gun carriage from Colombo port to Kandy and ceremonially interred amidst military honours on November 26, 1954 in a memorial which was constructed at the Kandy Esplanade opposite the Dalada Maligawa. Since then the Keppetipola commemoration day is celebrated every November 26th in the outer courtyard of the Kandy esplanade. Aspecial decree issued last year overturned the Government Gazette of 1818, decriminalising 19 freedom fighters including Keppetipola Disava and officially declaring them national heroes.

The Kandyan Chief known for his magnanimity towards the Sasana gifted a temple in his ancestral village of Moneravila, Pallepola. This historical site off Matale, however, is little known today. The abandoned shrine room of this temple which is presently known as Pallepola Veluwanaramaya, is crumbling.

The village derives its name ‘Moneravila’, from the water hole (vila) in which peacocks (monara) used to bathe, replaced by paddy fields today. The walls of the shrine room adorned with Kandyan art, commissioned by the warrior Chief are inhabited only by nocturnal creatures! A veeatuwa which bears signs of one-time regal Kandyan splendour including wall-paintings is left to the mercy of nature. A jewellery box, a chunam box and several artifacts which mirror Kandyan craftsmanship are deposited in the modern temple compound. These, as the temple’s Chief Prelate, Melpitiye Wimalaratana Thera informs us are presumed to be Keppetipola family heirlooms. A kurahan gala and a palekkiya (a type of Kandyan palanquin used among the nobility) still survive.

The Keppetipola residence at Hulangamuwa. Pix by Indika Handuwala

“When the skull of Keppetipola Disava was returned to the country, it had been on display at the old bana maduwa for the villagers to pay their respects,” says the prelate sharing a faded photograph from 1954. When he had first arrived in the village in 1964 as a young priest, certain portions of the ancient walauwa had existed, recalls the chief priest who adds that they were demolished to give space to the modern structures of the temple which stands there today.

Born in Udugoda, Udasiya Pattuwa, Matale as the second son to Golahela Nilame (who held the office of Diyawadana Nilame under Rajadhi Raja Sinha) and Moneravila Kumarihamy, Keppetipola Disava had five siblings-two brothers and three sisters, according to historical sources. The ill-fated Ehelepola Kumarihamy who bore the child hero Madduma Bandara was one of his sisters.

On the settlement which followed the Kandyan Convention of 1815, Governor Brownrigg appointed Keppetipola, Maha Disava of Uva. However, the Chiefs who signed the Convention soon realised the ‘unpalatability of the new regime’ as Judge Walter Thalgodapitiya in his work, Portraits of Ten Patriots of Sri Lanka notes. ‘Those were the forces working in the country in those unhappy confused times- disappointment, disillusionment and dismay,’ says the author who further cites a Kandyan Chief believed to have told the British – ‘you have now deposed the King, nothing more is required; you may leave us now.’ But the British had no such altruistic intentions as the author observes, and ‘the disillusioned Chief, sadder and wiser after the event (the Convention) plotted and planned with active encouragement of the priests to achieve that end.’ William Tolfrey, Chief Translator to the British Government who was stationed in Kandy from 1815 to 1817 perceived this spirit of revolt and wrote to the Governor that, ‘a deep and extensive plot to annihilate British power’ was being organized in the Kandyan provinces.

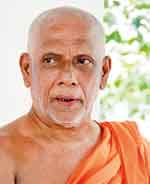

Ven. Melpitiye Wimalaratana Thera

It is in this backdrop the Great Revolt of 1818 or the Uva Rebellion broke. Keppetipola Disava who was initially sent by the British to curb the uprising, returned all arms and ammunition to the British and joined the rebels in Alupotha. He was supported by several other leaders who were ostracized as traitors by the British. “While serving at Sath Korale, Keppetipola Disava had also overlooked Matale and for more efficient administration, he had resided at Matale Udasiya Pathu and also in his mother’s village of Moneravila,” explains Nalini Chitra Keppetipola Vidurupola Aluvihare of Diyakelinawala Maha Walauwa, a sixth generation descendant of Keppetipola Disava and the chief mobilizer of Keppetipola descendants forum. As one of the most powerful Chiefs of Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe’s court, Keppetipola Disava was entrusted with scores of responsibilities which in turn called for regular travelling between the royal court and his residence in Moneravila in Pallepola. “As a place of rest for both Disave and his horses, another residence in Hulangamuwa, Matale was built,” says Mrs. Aluvihare. The house which reflects Kandyan architectural splendour is sadly neglected today.

Keppetipola married Delwala Ethanahamy from Ratnapura and had a son who was named Loku Banda. “The British wanted no direct descendant of the Disava spared and to evade the hunt, his son Loku Banda had to live in disguise and most of the Keppetipola land was confiscated,” Mrs. Aluvihare says.

A man who knew not the meaning of fear, Keppetipola Disava was tried by Court Martial on November 15, 1818. Henry Marshall documents in his book that he was least cowed by his impending doom and even engaged in jovial banter.

Marshall places on record the last moments of the Chief: ‘Kneeling before the priest upon the threshold of the sanctuary, the repository of the Sacred Relic, the Chief detailed the principal meritorious actions of his life such as the benefits he had conferred on the priests, together with the gifts which he had bestowed on the temples and other acts of piety. He then pronounced the last wish, namely that in his next birth, he might be born in the mountains of the Himalayas and finally obtain nirvana.’ The only worldly possessions he had- the ‘ragged upper cloth from the waist’ he offered to Dalada Maligawa as his last pious act and his bana potha he gave to a local official to be delivered to Simon Sawers, an agent of the government, as a token of the gratitude he felt for his friendship and kindness while they were officially connected at Badulla.

Chitra Nalini Aluvihare

Marshall who thus documents the end of Keppetipola Disava, on November 25, 1818, goes on to note: ‘Had the insurrection (1818 Uva rebellion) been successful, Keppetipola would have been honoured and characterised as a patriot instead of being stigmatised as a rebel and punished as a traitor’.

The sword of Keppetipola Disava and his flag, head dress and jacket are preserved in the Kandy National Museum today. Interestingly, Keppetipola who was a signatory to the Kandyan Convention as the Disava of Matale, had signed the document in Sinhalese along with the other two Chiefs-Galagoda and Galagama, unlike the others who signed in Grantha- a combination of Sinhalese and Tamil characters.

Ven. Yatigammana Vimalagnana Thera of the Malwatte Maha Vihara Sangha Sabha in his address at the ceremonial internment of the remains of Keppetipola Disava on November 26, 1954 noted: ‘If he should be here in spirit now, he would know how well he has served his people. There have been many men of our race after him to bear steadfastly and pass on, the flame of patriotism which in death he enkindled and to encompass the end for which he laid down his life.’