“Arthur of Serendip”

Journey’s end: Arthur C. Clarke at his Barnes Place home with two beloved pets. (The Sunday Times file pic)

As we proceeded down Kynsey Road, Swami suddenly shouted at me over the din of the sick engine, “Quick! Turn down Barnes Place!” Simultaneously I yanked at the slack wheel and pumped at the nonexistent brakes. We careened into Barnes Place, narrowly missing an assortment of humanity

“It’s Arthur’s 60th birthday in a couple of days! We must wish him all the best before we go to Kandy!” Swami said by way of explanation as I recovered control of the car. “Besides,” he continued, “we should get his blessings for our project.”

As I parked the car I wondered whether Arthur would have sufficient mental space to show any interest in our project. But then I consoled myself with the thought that Swami had known him for a quarter-century and that for a fair portion of those years he had been his close friend and occasional creative collaborator.

Arthur greeted us in his study with a meaningful grin – a mixture of relief, ecstasy, triumph and sheer satisfaction – which tells you when it adorns the face of an author that he or she has finished some major work and is now experiencing post-delivery euphoria. “Your arrival couldn’t be better timed” he informed us, “because today I have finished the first draft of my new novel The Fountains of Paradise.”

Before we could react to the good news Arthur’s euphoria ebbed. He announced in a more sombre tone, “I have to tell you that it’s going to be my last book – positively the last!” Thankfully that particular personal prophecy, unlike the majority of his scientific ones, was not to come to pass.

I was reminded of that meeting some years later when I read in Neil McAleer’s Odyssey: The Authorised Biography of Arthur C. Clarke (1992): “Arthur always felt a sense of elation when he finished a work, and the feeling had a decided influence on how he perceived any recently completed book. He was especially pleased with The Fountains of Paradise because his beloved tropical island played such an important part in it.”

McAleer has played an indispensable role in the archiving of Arthur. The 2nd edition of his official biography was published in 2012. He informs me that this was “the largest, full-life revision, edition revision”, while “the 3rd edition is a smaller revision to celebrate Arthur’s 100th birthday, and a big gala and dinner will take place in Washington, D.C., at George Washington University on December 9, a few days before his birthday.”

The biographer added, with understandable sentiment: “Believe me, this is the last edition for me.”Thus it was that last year 12 cubic feet of McAleer’s Clarke archive, organized and enhanced by the author’s descriptions, joined the much larger collection of materials at the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

The making of Odyssey

One morning in February 1964, an employee of the General Post Office in Colombo arrived at work not knowing that this was to be an extraordinary day. In fact, he was forever to remain blissfully unaware of the essential difference of that day, as well as his role in the scheme of things. His job, in an era of primitive communications, was to deliver overseas cables by hand, and on that particular, fateful day, he was destined to deliver one to a house down Gregory’s Road in Colombo 7.

Certainly he would not have been pondering the mysteries of the universe and the possibility of extra-terrestrial life, or musing on a project to encompass these themes in a major Hollywood movie. Yet such matters comprised the contents – and the outstanding potential – of the cable his fingers now held firm.

As he checked the name in his delivery book against that on the cable, perhaps he noticed the recipient was a sudhu mahattaya. Perhaps he had delivered other cables to this house; had come to learn that the Occidental resident was a writer of futuristic stories set both among the stars and beneath the seas. Perhaps he was familiar with the name Arthur C. Clarke and had even caught a glimpse of the man himself on a previous delivery. What he could not have comprehended on that February day was his role as a messenger of the muse of creation, for the cable was to be instrumental in bringing together two fine minds in one of the most fruitful collaborations in the history of cinema.

Reading the cable, Arthur found that it was from a friend, Roger Caras, inquiring whether he would be interested in “doing a film on ET’s” with the Stanley Kubrick, whose recent release Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb was fast gaining critical acclaim. The cable ended with a remark by Caras that Kubrick “thought you were a recluse”.

Caras was having lunch with Kubrick in New York and asked the director what type of film he intended to make next. Kubrick replied he wanted to do something on extra-terrestrials, that he was reading “everything by everybody” to find a suitable writer and collaborator for the project. When Caras suggested he should “start with the best” – Arthur of course – Kubrick replied, “But I understand he’s a recluse, a nut who lives in a tree in India someplace”. Caras retorted, “Like hell. He’s not a recluse or a nut. He just lives quietly in Ceylon.”

Saddled with such misconceptions, Kubrick must have been surprised to learn that Arthur had been far from reclusive or inactive in the eight years he had lived in Ceylon. He had travelled abroad regularly on lecture tours. He had been beneath the seas around the island along with Mike Wilson and Rodney Jonklaas. He had even headed a successful underwater treasure hunt, and, if proof was necessary, the clumps of silver coins salvaged from the wreck off the Great Basses Reef nestled in a chest in his study.

Things happened at a surprising pace after Caras’ cable was delivered and the contents digested. Not wishing to waste such an opportunity as none of his stories had been produced as a film, Arthur promptly replied Caras: “frightfully interested in working with the enfant terrible”.In addition, he requested Kubrick to contact his agent, Scott Meredith. Following discussions with Meredith, Kubrick wrote to Arthur for the first time in March, a few weeks later. “He wanted to do the proverbial ‘really good’ science fiction movie,” says Arthur of this letter. Kubrick went on to list his main interests in pursuing the theme of extra-terrestrials: “(1) the reasons for believing in the existence of extra-terrestrial life, and (2) the impact (and perhaps lack of impact in some quarters) such a discovery would have on Earth in the near future.”

This letter further aroused Arthur’s curiosity and he became anxious to meet Kubrick to discuss the project in more detail. Fortunately, he was due to travel to New York to complete work on Time-Life Science Library’s Man and Space, the main text of which had been written in Colombo. Arthur prepared for his eventual meeting with Kubrick by trawling through his published fiction for ideas that could be used for the type of film envisaged. “I quickly settled on a short story called The Sentinel, written over the 1948 Christmas holiday for a BBC contest,” Arthur reminisces in McAleer’s biography. “It was this story’s idea which I suggested in my reply to Kubrick as the take-off point for a movie. The finding – and triggering – of an intelligence detector, buried on the Moon eons ago, would give all the excuse we needed for the exploration of the Universe.”

In the end six other stories would become elements in both the screenplay and novel of the film, but it was the decision taken in Colombo regarding The Sentinel that initiated the elaborate creative process.

Arthur embarked on the journey from Colombo to New York in mid-April 1964 not knowing the project would delay his return to Ceylon until June of the following year. During this time a number of milestones in the project would be reached – a collaborative agreement between Arthur and Stanley Kubrick, the writing of the novel, if not the screenplay, and the decision by MGM to fund the project. But production did not begin until December 1965.

It was in April 1965 that Kubrick chose the title 2001: A Space Odyssey. Thirty-five years into the future, 2001 was felt to be distant enough in time to ensure that the film’s future realism would not be undercut by reality. The year 2001 has been inextricably associated worldwide with the film.

Sri Lanka, his adopted home

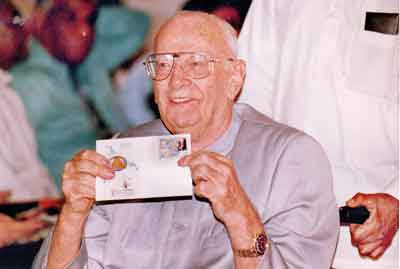

Arthur C. Clarke being honoured with a first day cover in 1999 to mark 50 years of communications in Sri Lanka

Although Sri Lanka, as literary critic Andrew Robinson expressed it, “does not impinge much on his prolific best-selling fiction and non-fiction”, Arthur wrote some notable and quotable pieces extolling the island’s virtues for the modern traveller. Possibly the best piece of this nature he created for Roloff Beny’s Island Ceylon (1970), to my mind the most impressive coffee-table book about the country.

“It may well be that each of Ceylon’s attractions is surpassed somewhere on Earth,” Arthur commented in the epilogue. “Cambodia may have more impressive ruins, Tahiti lovelier beaches, Bali more beautiful landscapes (though I doubt it), Thailand more charming people (ditto). But I find it hard to believe that there is any country which scores so highly in all departments – which has so many advantages, and so few disadvantages, especially for the western visitor.”

A similar passage I have always admired, written for BOAC, now British Airways, makes the important point that the island is a veritable microcosm – and that visitors should quit Colombo if they wish to see the real country.

“The Island of Ceylon is a small universe; it contains as many variations of culture, scenery, and climate as some countries a dozen times its size. What you get from it depends on what you bring; if you never stray from your hotel bar or the dusty streets of Westernized Colombo, you could perish of fulminating boredom in a week, and it would serve you right. But if you are interested in people, history, nature and art – all the things that really matter – you may find, as I have, that a lifetime is not enough.”

Arthur was philosophical when he wrote of his relationship with Sri Lanka. In an article for the London Observer for instance, he discussed the significance of the two principal beaches in his life: Minehead, in Somerset, where he grew up, and the other Unawatuna, which he discovered much later in life.

“One day, after a lecture somewhere in the American Midwest, a young lady asked me why I liked Ceylon. I was about to switch on the soundtrack I had played a hundred times before, when suddenly I saw those two beaches. Do not ask me why it happened then; but in that moment of double vision, I knew the truth. The drab, chill northern beach was merely the pale reflection of an ultimate and long-unsuspecting beauty. Like the three Princes of Serendip, I had found far more than I was seeking – in Serendip itself. Ten thousand kilometres from the place where I was born, I had come home.”

In addition, there is this passage from The Treasure of the Great Reef (1974): “Always it is the same; the slender palm trees leaning over the white sand, the warm sun sparkling on the waves as they break on the inshore reef, the outrigger fishing boats drawn up high on the beach. This alone is real; the rest is but a dream from which I shall presently awake.”

Events of past decades meant that Arthur had to contend with something of a Lost Paradise, where his “slender palm trees” had been bulldozed to make way for yet another insipid hotel; where his “beautiful landscapes” had become scarred by development and erosion; where his “charming people” had been stunned by incessant conflict and violence.

Arthur is one of a small but celebrated band of British writers – others include D. H. Lawrence and Anthony Burgess – who led fulfilling and enriching expatriate lives. It is impossible to spend decades in an adopted country without becoming inextricably wound up in its fate and Arthur was no exception. He showed consistent concern for the future direction, well-being and prosperity of Sri Lanka. Whether it be his pioneering underwater explorations, his eloquent writings, his contribution to the Arthur C. Clarke Centre for Modern Technologies, or even his occasional newspaper correspondence on subjects as diverse as daylight saving and Senerat Paranavitana’s interlinear inscriptions at Sigiriya, Arthur showed an unwavering commitment to his beloved tropical island. He is, without doubt, “Arthur of Serendip”.

This recollection of Sir Arthur C. Clarke has been compiled from various birthday celebrations and accounts of the making of 2001: A Space Odyssey that have appeared in The Sunday Times over the past two decades.