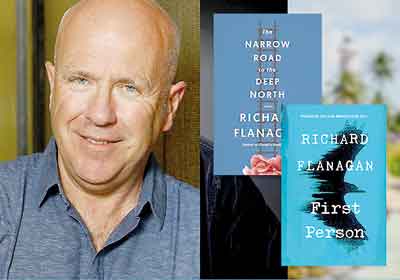

Richard Flanagan: Ghost writing a ghost

View(s): Richard Flanagan won the Man Booker prize in 2014 for The Narrow Road to the Deep North. But it was his latest book ‘First Person,’ which has the longer history: “First Person is the book I began before the Booker and which I finished after, while at the same time, trying to surf the mudslide that the Booker brings on without falling off and being buried alive,” Richard told a journalist from The Guardian.

Richard Flanagan won the Man Booker prize in 2014 for The Narrow Road to the Deep North. But it was his latest book ‘First Person,’ which has the longer history: “First Person is the book I began before the Booker and which I finished after, while at the same time, trying to surf the mudslide that the Booker brings on without falling off and being buried alive,” Richard told a journalist from The Guardian.In First Person, would-be novelist Kif finds himself embarking on the ghost-writing job from hell. Flanagan told a journalist from The Guardian how in 1991, while working as a builder’s labourer and trying to write his first novel, he was offered $10,000 by Australia’s greatest conman and corporate criminal, John Friedrich, to ghost-write his memoirs in six weeks.

“He had embezzled a billion dollars in today’s terms, set up a sort of a secret army and the whole thing had gone belly up. His bodyguard was a mate, which was how I got the gig. We worked on the book for three weeks and then he shot himself dead. I was left to ghost-write a ghost.”

Even beyond the bare lines of the plot, Flanagan and his fictional ghost-writer have other things in common – not least in how challenging it has been to make a living as a writer.

Flanagan is one of only four Australians to win the Man Booker Prize but before he won the £50,000 Booker, Flanagan was thinking of returning to manual labour to make a living. It wouldn’t have been that different from what his parents expected of him: “My mother had high hopes for me and thought, with application, I might make a good plumber. I had the folly of thinking I might even aspire to being a carpenter, but secretly all I ever wanted to be was a writer. I can’t believe I’ve made it to 56 with no one blowing the whistle on me – yet.”

Flanagan grew up in the remote mining town of Rosebery on Tasmania’s western coast, the fifth of six children. He is descended from Irish convicts transported during the Great Famine to Van Diemen’s Land. Flanagan’s father was a survivor of the Burma Death Railway.

His father’s story was intrinsic to The Narrow Road to the Deep North, which told the life story of Dorrigo Evans, a flawed war hero and survivor of the Death Railway. The Booker changed his life and let him continue as a writer, and much of that had to do with the prize cheque. He told a journalist from The Australian: “Look, being a writer is a journey into endless disappointments and failures…But I have been lucky enough, too — the Booker was a catastrophe of good luck — and I am still able to write, so I am grateful.”

His father’s story was intrinsic to The Narrow Road to the Deep North, which told the life story of Dorrigo Evans, a flawed war hero and survivor of the Death Railway. The Booker changed his life and let him continue as a writer, and much of that had to do with the prize cheque. He told a journalist from The Australian: “Look, being a writer is a journey into endless disappointments and failures…But I have been lucky enough, too — the Booker was a catastrophe of good luck — and I am still able to write, so I am grateful.”

The author has been frank about the challenges of swinging from a period of struggle to great success. He likes to tell a story about the best advice he was ever given, that has helped him keep his head through it all.

“When I was young, I won a scholarship out of Tasmania that got me to Oxford. I went to tell my parents. My mother was peeling vegetables and took it in the manner of a radio update on the football score, and suggested I tell my father who was out the back turning the compost. I told him my news. He never turned around. He said, reciting Kipling: “If you should meet with triumph or disaster treat these two impostors just the same.” And that was that. I laughed and left. But he was right.”