An ocean of gratefulness still flows

A rare photograph of D.S. Senanayake at the Gal Oya site

From atop Inginiyagala, he is the master of all he surveys. Spread before him, to his right is the massive ‘Samudraya’ (ocean), with its waters, taking on a golden hue, glistening in the setting sun and to his left are lush paddy-fields in their green glory.

Awe-inspiring is the Gal Oya Multipurpose Scheme with its heart being the Senanayake Samudraya, still retaining the No. 1 position more than 69 years after it was commissioned.

Modern machinery of that era as well as elephants had been utilized for this pioneering project to take shape off plans on drawing boards to the hard ground of Ampara.

As Sri Lanka celebrates its 70th Independence Day, it is still the Father of the Nation, D.S. Senanayake, who is revered by the humble peasantry of Ampara for giving leadership to the Gal Oya Scheme.

We start our journey to the 1950s not at the point where the icy waters of the 108-km Gal Oya flow forth from the mist-laden mountains of Badulla, but at the point where it is dammed to harness its waters which earlier went into the sea, south of Kalmunai in the east…..the spectacular vista of the Senanayake Samudraya on one side and on the other the hydro-power turbines, the fresh-water fisheries tanks and the vast tracts of paddy.

The Gal Oya Multipurpose Scheme: Awe- inspiring panoramic view. Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

“Never has the Senanayake Samudraya gone dry,” says Ampara’s Director of Irrigation, Eng. K.D. Nihal Siriwardhana, seated before a large map of this scheme, while adorning a full wall at the entrance to his office is a colourful artist’s impression of it.

In the early days, long before the Gal Oya Scheme, Ampara was at the receiving end of both droughts and floods. It was to ward off these natural calamities and cushion the peasantry, the backbone of this rice-eating country, that it was implemented by the visionary D.S. Senanayake, after Sri Lanka had just shed the shackles of colonialism.

Dammed they did the Gal Oya, creating the Senanayake Samudraya, the largest reservoir in the country, sending out water along the Right and the Left Bank canals to irrigate 120,000 acres of which a large acreage is still under paddy and a smaller acreage (about 11,000 acres) under sugarcane cultivation. The project also incorporated the ‘River Division’ cultivations which had been carried out using anicuts downstream, before the scheme came into operation.

There were two groups of people who were settled in the villages ‘carved from the jungle’ around the Gal Oya Scheme.

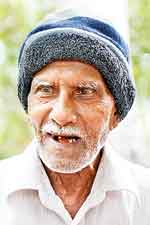

Eng. Nihal Siriwardhana

“They were those displaced by the waters of the reservoir who were given lands in lieu of those they had lost and others who were brought from far off lands and resettled in the area (colonists),” says 85-year-old Ekanayake Mudiyanselage Appusingho in Polwatte. He himself from Bandarawela did not come as a colonist but to do wadu-weda (carpentry) as he was working at the Small Industries Ministry then and formed the construction team which put up the shuttering and also built the silos in which the paddy harvests would be stored later.

He met and married K.A. Podi Menike, now 74, who had come as an eight-year-old with her parents from Gonagala in Kegalle to make their home as colonists here.

Colony hathalihak hadala minissu dura gam walin genawa, says Appusingho, as Menike nods vigorously. (Forty colonies were established with people brought from distant areas.)

Menike relives those early years when her father left his ancestral home and hearth and arrived with only his family and bundles of clothing to make a life here. Large swathes of land had been “dozered” bare. Each colonist family was given “everything” — a small cottage with three rooms, all tools such as mammoties, pannittu (buckets), kethi (sickles) needed to cultivate the land as also a harak banak (a pair of cattle) for ploughing, along with a four-acre mada idama for paddy and a one-acre goda idama for big and small trees including coconut and mango.

Podi Menike

Vivid are Menike’s memories – how they went to Polgahawela, took the train to Batticaloa and due to violent protests by the locals, they got onto lorries with the army being deployed to provide a guard from the Railway Station to their brand new homes. In Batticaloa, they had a rice and fish meal and once in their homes were given half a loaf of bread each with seeni-sambol. Later rice rations were from the cooperative until they got a yield from their paddy-fields.

Sweat and toil were the routine of the early days at the new frontier, wracked by the fevers of malaria, with an ambulance “like a lorry” taking the sick to hospital.

Of the colonized villages, earlier “gana wanantare” (dense jungle) infested with wild animals including elephants, 36 were occupied by the Sinhalese and the others by Tamils and Muslims.

In 1957, came the great flood, says Menike, with fears that the Senanayake Samudraya would breach its bunds. The panicky colonists “suddanta telephone kara”, assuming that the foreigners would rush there and release all the water from the reservoir to overcome the danger. The foreigners did come but the reply was unexpected…….“Umbalage kandu deka vishwasa nethivunath, bemma kedenne ne.” (Even though the two hills between which lies the Senanayake Samudraya are not sure, the dam will not give-way.)

Former Minister: P. Dayaratne

Their words have held true even today, says Menike in amazement.

On the directions of the Appusingho-Menike couple, we cross the Left Bank canal at Alioluwa Handiya to go to the home of 78-year-old Herath Mudiyanselage Gunaratne.

“Ithama dushkarai api enakota, yana-ena paraval thibbe ne, guru paraval witharai thibbe,” says Gunaratne whose family came from Badulla, explaining how remote the area was sans roads, only dusty tracks. His father grew oranges for a living but decided to take a chance in the new world of Gal Oya. They were amongst the first settlers, arriving to a literal desert, with all vegetation cleared by huge machinery and set ablaze in the village of Wawinna. Their new houses were of cement-block walls and tile-roof while a school in the area before the scheme sported only goma-meti biththi (mud walls) and an iluk-thatched roof. The colonists were issued balapatra (permits) for the land they cultivated which were later changed to Swarnabhoomi or Jayabhoomi deeds.

E.M. Appusingho

Gunaratne attended the new village school which had on its register about 140 children and was the first to pass the Senior School Certificate from there, after which he trained as a teacher and returned to serve the area, retiring as a Principal.

It is in the garden of the Ampara Hospital that we meet 63-year-old Digamadulle Ranawira who has been discharged after a scan. He has written two books, ‘Gal Oya Nilame I & II’ in Sinhala on the lives of the “Gal Oya colony karayo” at the urging of his father.

His father was from Hindagala, Peradeniya and his mother from Dunkewila, Gampola. News filtered to Gampola that Gal Oya needed settlers. There were two conditions of settler-eligibility – they could not own an inch of land and their eldest should be a son. “Thaththa had as the eldest a daughter,” smiles Ranawira but the Arachchi wanted him to state otherwise.

Seventy-two applications went from their village and nine families, eight of whom were closely related, were chosen after medical check-ups. It was 1952 and a lorry picked up the walang-pigang, latta-lotta (knick-knacks) and dropped them at the Gampola Railway Station. When they de-trained at Batticaloa, they were met by a Colonization Officer and two Village Officers.

D. Ranawira

Gal Oyata paya thibba gaman mal vessak vessa, says Ranawira recalling what his father had told him how there was a mild shower of rain auguring well for the colonists. He too ticks off on his fingers what was provided to the colonists including lantherum (lanterns), 400 rupees to buy cattle for ploughing and two busal of bittara wee (seed paddy) of the Illankaliya variety. D.S. Senanayake mahattaya colonistslata avashya hema dema dunna. (The colonists were given everything they needed by D.S.)

“They were expected to cultivate paddy with rainwater and after they had eaten rice from two or three kanna (seasons), they were promised water from the Left Bank canal of the Gal Oya Scheme,” he says.

Long-time Ampara politician P. Dayaratne puts things in perspective when he says that the motive of D.S. Senanayake was to make then Ceylon self-sufficient by opening up new lands for paddy. Then Director of Irrigation, J.S. Kennedy who was working in the east, realized the potential of creating a large reservoir by damming the Gal Oya.

Did you know that the catchment area of the Senanayake Samudraya is in the Uva Province, while the waters actually benefit those living in the Eastern Province, he asks.

H.M. Gunaratne

The rest, of course, is history. But former Minister Dayaratne’s contribution had come later. Explaining that the efficiency of an irrigation scheme lies in releasing the right quantity of water at the right time, he says that there was much wastage, with no management and conservation. People did not realize that water is precious.

Around 1977-78, when he was a young Member of Parliament, the colonists came to him with complaints about water shortages. On his request to Mahaweli Development Minister Gamini Dissanayake, the Gal Oya Rehabilitation Scheme was launched. It resulted in the use of 8 acre-feet of water for 1 acre of paddy being cut to 3.5 acre-feet of water.

Farmer Organizations were also set up with the understanding that the ‘main channels’ under the Gal Oya Scheme would be looked after by the Irrigation Department, the ‘distribution channels’ jointly by the department and the farmers and the ‘field channels’ by the farmers, giving them ownership in this largest paddy producing district of Sri Lanka. This pilot project was replicated across the country.

Ironically, our search for photographs of the ‘Man behind the project’ D.S. Senanayake yields little results. We spot one fading black-and-white photograph of him at the Gal Oya site in the Golden Jubilee souvenir (1949-1999) of the Gal Oya Development Project.

It is also in the same book that historian K.M. de Silva confronts the allegations levelled that Sinhala colonists were brought into the “traditional homelands of the Tamils” stating: “Gal Oya and most of the other major colonization schemes of the Eastern Province were located in areas which were either the sites of remnant Sinhalese villages or were under the jungle tide.”

As we gaze over the Senanayake Samudraya before heading back to Colombo, what the poet said in ‘The Brook’ comes to mind with the adaptation “men may come and men may go, but Gal Oya goes on forever”. This is fortified by the colonists that Don Stephen Senanayake may be no more, gone a long time ago even before the Gal Oya Scheme reached its full potential, but lives in their hearts forever.

“Ape deviyo D.S. Api unu unu bath tikak kanakota, apita mathakvenne DS,” says Menike, summing up that their god is D.S. and whenever they eat a steaming plateful of rice they remember him.

| Page by page the story of the Gal Oya project | |

Elephant strength for the Gal Oya project (Pic from the Ampara Irrigation Office) The Gal Oya Multipurpose Scheme unfolds from the tomes of the Master Plan and other books preserved by the Irrigation Department. Gal Oya or Pattipola Aru as it was known then was notorious for seasonal flooding and long periods of drought. There were calls for a project to mitigate downstream flooding and serve as a controlled source of irrigation water, produce hydro-electric power and be a source for the domestic water supply. In 1913, the Gal Oya Project took seed in the mind of Batticaloa Irrigation Engineer J.S. Kennedy, with the idea blossoming when he became Director of Irrigation in 1935. 1936 – Kennedy summons a conference with senior irrigation officials to discuss the proposal for the first-ever multipurpose project. Initially, a hydrological gauging station is established and engineering surveys are conducted. Later the final location 35 miles upstream from the river mouth is finalized. 1941 – The first Sri Lankan Director of Irrigation, W.I.T. Alagaratnam, produces the first preliminary feasibility report but due to World War II there is little progress. 1947 – The report is revived and plans, studies and supporting data are prepared and renowned dam expert, Dr. J.L. Savage, approves them. November 30, 1948 – The contract for the construction (earth-fill dam, the mass concrete spillway and the powerhouse with separate outlet and tailrace) at Inginiyagala is awarded to Morrison-Knudsen International Co., of America. December 1949 – The statutory Gal Oya Development Board (GODB) comes into operation led by civil servant K. Kanagasundram with the Resident Manager being Shirley Amerasinghe. March 1949-November 1951 — Construction of the Gal Oya Scheme. 1952 – The Irrigation Department completes the irrigation headworks and hands over the project to the GODB. Thereafter, the GODB completes the Left Bank canal system and the tanks of Namal Oya, Aligalge, Himidurawa, Walagama and Navakiri Aru and the Right Bank canal system and the tanks of Jayanthi wewa, Ekgal Aru, Alahena and Malayadi. Meanwhile, several more existing tanks are incorporated into the Gal Oya Project: On the Left Bank, Kondavattavan, Amparai, Valattapiddy, Verragoda, Kadukkamunai and Chadayantalawa and on the Right Bank, Irrakkhamam Tank. 1951-52 onwards – Displaced families as well as families mainly from the Wet Zone are settled in the colonies. Nearly all are Sinhalese, selected on the basis of landlessness, size of family and background in peasant agriculture. Our research reveals that the 32-mile Left Bank canal provides irrigation facilities to 80,000 acres and the 21.5-mile Right Bank canal serves 40,000 acres, with the whole project being carried out and paid for with local resources and managed by local administrators. A small quantum of funds had been from the Colombo Plan and the United Nations.

|