News

Health service nutrition failures a factor in alarming child malnutrition

Nutritionists and paediatricians agree with the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization’s findings that Sri Lankan children under five years of age are suffering from malnutrition that prevents them from reaching their full potential.

The recent report said that the prevalence of wasting — low weight for height — in children under five years stood at an alarming 21.4% and stunting at 14.7%.

The FAO recommended that the government strengthen its nutrition policy to prevent the disastrous effects, including impaired learning ability and lethargy.

The Sri Lanka College of Paediatricians, said that failure to create awareness of the value of nutrition and the choice of food have contributed to the problem.

President, Dr Asiri Abeygunewardena said that the education system focuses mainly on curative care and has failed to consider the strengthening of the nutrition status.

“Our education system has given more priority to treating sicknesses, rather than taking preventive measures,’’ he said.

He said that focusing on the nutritional awareness of pregnant women could have long-term benefits.

The nutrition and immunisation of children under five years, is done by the Family Health Bureau. The bureau carries out its programmes through the Medical Officers of Health, midwives and health officers. The programmes have not been effective, as the FAO report proves.

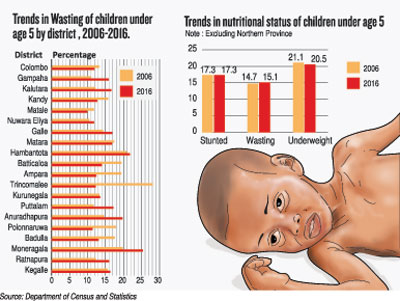

According to the Census and Statistics Department’s demographic and health survey of 2016, 17.3% of children below five years are stunted.

The situation has existed for the past 10 years.

However, there is a slight improvement in the measure of underweight children (down 1.5%) and wasting (down.4 per cent) , compared to the 2006 figures.

The prevalence of wasting in the district of Colombo which was 13% is 2006, has improved to 12%. Wasting in the past 10 years has remained high in most districts with a record high of 25.5% in Moneragala in the Uva Province.

There is just one district general hospital in Moneragala, a highly rural area.

In the districts of Puttalam and Anuradhapura wasting is at 19.5%.

Interestingly, the war-ravaged districts of Batticaloa, Trincomalee and Ampara have shown considerable improvement in the last 10 years, with a 6.5% to 15% drop in the numbers. In the Trincomalee district that had the highest percentage (28%), it has declined to 13% in 2016. More research has to be done to understand how these districts without specific intervention from the health sector had improved.

Prof Abeygunewardena points to failures in the education system for the existence of underweight and stunted children. Pregnant women and young mothers are not made aware of the value of nutrition in having healthy children.

“More emphasis has been given to addressing issues like dengue. Though our mortality rate has gone down, we are facing nutritional problems. Our neonatal care may be good, but preventive care is lagging,’’ he said.

He said Sri Lankans seem not to care enough about choosing nutritional food for their children.

Undernourishment is confined not only to the rural population but also found in urban Sri Lanka where city mothers often feed their children with biscuits and quick meals to cut down on time spent preparing a nutritious meal.

On a brighter note, Sri Lankan women are almost at the top on the breast feeding chart. The UNICEF report 2016 places Sri Lanka second in the list (78.4%) of mothers who breast-feed their babies during the first six months.

But this could also be explained by the high cost of infant milk formula in the country. The majority of Sri Lanka’s mothers are very poor and cannot afford infant formula long-term. More than 75% of Sri Lankans live in rural areas. Nearly nine million Sri Lankans do not even have access to water.

Rwanda tops the breastfeeding list with a high of 87%.

However, when it comes to weaning infants off breast milk and feeding solids, Sri Lankan mothers are apprehensive, and often prefer to give infant formula, or ‘congee’ – water strained from cooked rice.

Prof Abeygunewardena notes the importance of feeding mashed nutritious solids after six months of breastfeeding.

The ‘congee’ he said has very little nutrition in terms of kilo calories. A cup of 100 millilitres of ‘congee’ has only 20 kilo calories, whereas 100mls of milk has 70kc. As a result, the infant does not get enough nutrition.

“Feeding smashed solids should start at least at six months or even earlier,’’ he said.

Having recognised the need to create awareness among child-bearing women, the paediatricians have started a programme to educate pregnant women through maternity clinics. The doctors, midwives and health workers are educated on the types of food that could be given to infants during the weaning period.

This knowledge is passed on to pregnant women during their monthly visits to clinics and the family doctor.

Since 2016 the programme has covered Nuwara Eliya, Ratnapura and Galle districts. “There has been a lot of interest. We hope to cover the northern and eastern provinces, soon,’’ Prof Abeygunewardena said.

Former Industrial Technology Institute head, Dr Janaki Gooneratne, said that although the Government spends billions of rupees on the health services it has not been able to address malnutrition.

She suggests taking another look at the Triposha handout.

“We have been distributing Triposha for the past 30 years but there has not been any remarkable improvement in children’s nutritional status. It is time we reviewed it,’’ she said.

“Triposha is a corn soya blend. Instead a change could be brought with a rice blend which will be easy on the local palate. This will be more nourishing.’’

The Family Health Bureau, she said, needs to “pull up its socks’’ and bring in more active programmes for young mothers. “Good instructions and demonstrations are needed to get the message across,’’ she said.

Also, there is lack of formulated food in the market for 6 to 12 month olds. During this time, if the child does not get the proper nourishment he or she lags behind in weight and height relative to age.

The president of the Nutrition Society of Sri Lanka, Prof Anoma Chandrasekera, said: “We need a specific strategy to target areas that have high prevalence,’’ she said.

Prof Chandrasekera said that not employing nutritionists in the health sector is also compounding the problem.

Hospitals do not employ nutritionists.

“Nutritional advice is important for a healthy society and they should be available for consultation,’’ she said.