News

Spoon-billed Sandpiper found in Sri Lanka!

View(s):The last record of a sighting in Sri Lanka was 40 years ago in 1978 and for many years, birdwatchers in the country have been on the look-out for it here.

The Spoon-billed Sandpiper at Vankalai Sanctuary. Pic by Ravi Darshana

As afternoon was slowly fading into evening, around 5 p.m. on June 6, an Executive in a finance company, Ravi Darshana, was returning home after work in Mannar, through the Vankalai Sanctuary when he saw an interesting sight.

At a water body, just 25 metres from the road, he saw a flock of 250-300 ‘loitering’ shorebirds. This was not the time of year for the sanctuary to hold multitudes of migrant waterbirds, for they had left two months before, most returning home far to the north of Sri Lanka, from where they had flown here to avoid the winter.

However, Ravi, a Ceylon Bird Club (CBC) member, could make out a mix of mainly Kentish Plovers and Lesser Sand (Mongolian) Plovers with a few Curlew Sandpipers and Little Stints. The latter three being the most numerous of the shorebird species that visit Sri Lanka and the first being quite common.

Two of the birds were feeding together separately from the rest and Ravi, focusing his binoculars on them, identified one as a Little Stint. The other, he noted, was of similar plumage but slightly bulkier in appearance……..and then he saw the unmistakable bill.

It was a Spoon-billed Sandpiper!

Ravi had spotted the little shorebird with the strikingly shaped bill, Calidris pygmaea, rated as ‘Critically Endangered’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The Sunday Times understands that the Spoon-billed Sandpiper has attracted much attention towards its protection in recent times. Seen in South India until 1996, there had been no records since then in that country, until April this year when it was seen in Bengal, adjacent to Bangladesh.

While the IUCN states that the Spoon-billed Sandpipers are “an extremely small population that is undergoing an extremely rapid population reduction”, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology points out that there could be “as few as 100 breeding pairs remaining”.

And on June 6, Ravi had seen this elusive shorebird, for whom birdwatchers in Sri Lanka have been on the alert because of the value to ornithology in knowing if its range had extended again and as a “prize” sighting.

Ravi, had joined the CBC a little more than a year ago, becoming an exceptional field ornithologist, recording one species new to the country and several which are very rare, in this brief time.

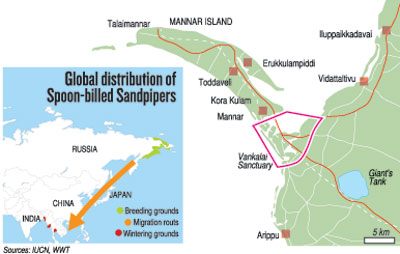

Spoon-billed Sandpipers breed in the eastern-most end of Asia and annually migrate along the shore of the continent to South-East Asia and the Bay of Bengal. Their population was naturally small to begin with and has declined dangerously. This is believed to be due to the loss of wetlands in its migratory and wintering range, caused by human activity, according to the CBC.

This has resulted in the setting up of a ‘Spoon-billed Sandpiper Task Force’ comprising numerous scientists and conservationists of many countries.

Explaining how Ravi had seen a flock of shorebirds, when most had left, the CBC said that young shorebirds which migrate for the first time, having left the breeding grounds a few months after their birth, do not return there at the end of their first winter. The great majority of them fly back part of the way to different summering grounds. A few of them ‘over-summer’ or ‘loiter’ on in the wintering grounds through the summer and stay the following winter as well. With some species this may happen a second time. After the next winter, they return home to breed. Until this time they also retain their less colourful winter plumage, which blends with their southerly surroundings.

Sri Lanka lies at the end of the great Central-South Asia ‘flyway’, one of the world’s major migration routes for birds which annually move south from the northern winter. For the hundreds of thousands of birds which winter in the island, there are two entry-and-exit pathways: The Jaffna Peninsula and Mannar, partly via the Adam’s Bridge islands. Most of the waterbirds remain in the north throughout the winter, staying within either region or flying between them.

It is possible that among these multitudes of birds, Spoon-billed Sandpipers arrived in Sri Lanka in any or all of the past years and were missed. The present bird was more conspicuous because it stayed on after the flocks of other shorebirds had left, the CBC said, adding that “now we know that the species still does migrate as far as its natural south-western limit, Sri Lanka, as it did before its population declined”.

The CBC is in contact with the Spoon-billed Sandpiper Task Force and Wetlands International regarding the find and the follow-up to it.

| Spoon-billed Sandpiper at a glance | |

| The Spoon-billed Sandpiper has a naturally limited breeding range on the Chukotsk peninsula and southwards to the isthmus of the Kamchatka peninsula, in north-eastern Russia…It migrates down the western Pacific coast through Russia, Japan, North Korea, South Korea, mainland China, Hong Kong (China), Taiwan (China) and Vietnam, to its main wintering grounds in southern China, Vietnam, Thailand, Bangladesh and Myanmar, according to the IUCN. Referring to its habitat and ecology, the IUCN states that it has a very specialised breeding habitat, using only lagoon spits with crowberry-lichen vegetation or dwarf birch and willow sedges, together with adjacent estuary or mudflat habitats that are used as feeding sites by adults during nesting. The species has never been recorded breeding further than 5 km (and exceptionally once, 7 km) from the seashore. |

| Protecting migrant birds | |

| Congratulating Ravi on the “wonderful” find of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper, the Ceylon Bird Club (CBC) Chairman Dr. Pathmanath Samaraweera says that the CBC kept the news limited for a short period of time to allow the study of the bird, as there is a present tendency for “photographic trophy hunters” to chase after rare birds, disturbing them. “The CBC is happy that Vankalai Sanctuary and Veditalativu Nature Reserve (NR) were declared as protected following up on the data provided by the club. We thank the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) for this and for further conservation measures even with limited resources in personnel,” he says, adding that the declaration was primarily to protect migrant birds. “If any ‘ringing’ is done we urge the DWC to observe or monitor and enforce, the stringent international rules which apply, to prevent any harm to them.” Referring to the wind farm in Mannar, Dr. Samaraweera says that they are disappointed that in spite of the extensive data and analysis supplied by the CBC highlighting the importance of the migratory pathway across which the wind turbines are to be constructed, the Ceylon Electricity Board and the Asian Development Bank chose to accept reports that stated that there was no significant collision threat to migratory birds from the wind turbines. Vankalai Sanctuary, a little over 4,800 hectares, and Veditalativu NR, even larger, together form an unbroken extent of land, one of the richest and most important waterbird areas in the world. They were declared protected areas in 2008 and 2016 respectively and Vankalai was named a Ramsar Site in 2010, all on data provided by the CBC. A CBC team carrying out its annual waterbird census at Veditalativu Lagoon in 2010, found a million shorebirds and in the Vankalai Sanctuary, it recorded half a million shorebirds in 2016 and 2018, and more than 100,000 waterbirds on several occasions. “There has been political pressure to de-gazette part of the Veditalativu NR for an aquaculture farm! The two protected areas have been encroached on already with political support or even initiative. These are not the only instances,” the CBC adds. |