Michael Ondaatje’s identity between history and fiction

Michael Ondaatje, born in 1943, is both outsider and insider in relationships with Sri Lanka, the country of his birth and very early childhood. He began his adult discovery of this country in the late 70s of the last century, and that part he was to share with the world is in Running In The Family and Anil’s Ghost. The latter book which grew out of the former appears to have been a vitally needed part of Sri Lanka’s 20th century history. The fiction of a novelist can do what social science cannot or will not do.

Most critics describe Michael Ondaatje, the poet and novelist, who for nearly 50 years has been a Canadian and an international figure, as being of mixed Dutch and Tamil ancestry.

In Running in the Family Ondaatje is brief about this matter:

“My father always claimed to be a Ceylon Tamil, though that was more valid about three centuries earlier.”

It comes from family lore that Ondaatje’s ancestor, a south Indian from Thanjavur, Undachipillai Balasingham arrived in 1660 to give medical attention to the daughter of the Dutch governor of Ceylon. At this point began the transformation of the Tamil into a Ceylon Burgher. He was rewarded with land, a Dutch wife and a Dutch way of spelling his old Tamil name.

Again in Running in the Family, referring to some of the circles of upper middle class families that moved closely with the Ondaatjes in Ceylon, in the 1920s and 30s, he says:

“Everyone was vaguely related and had Sinhalese, Tamil, Dutch, British and Burgher blood in them going back many generations.”

Students of Michael Ondaatje’s writing may be on acceptable grounds to consider him a Burgher, but only in the Ceylon and Sri Lankan categorization of people. Importantly, he is much less a Burgher in relation to the association of his identity with his writings on Ceylon and Sri Lanka. The various parts of this writer are an admixture of ethnic pieces but more crucially all these subsumed by a commonality that is man.

Ondaatje was sent from Ceylon to England at the age of 11 in 1954, for personal family reasons, not as part of the socio-political emigration of the Burghers. This story is told in The Cat’s Table. There is possibly significance in The Cat’s Table emerging in 2011, a whole decade after he had painfully exhausted himself out of Sri Lanka in Anil’s Ghost. It is as if he played a trick with time, getting out of that country, finally, in the innocence of a child, putting behind the torment with which he left after Anil’s Ghost.

On his arrival in England in 1954, he joined his divorced mother and may have become an English schoolboy. He says the transformation did not take place.

“I went to school in England and had every opportunity to become English, but I never felt I had the “ability”. I always felt very ironic.”

He did not see those four years in England in perspective, he says, till he saw the Pakistani-English Hanif Kureshi’s film My Beautiful Launderette, about colonial Asians in Britain (1985).

“It was very important to me. When I saw it I thought: God! That was my life in England, endlessly visiting all those Sri Lankan aunts and uncles and hearing stories.”

And then to Canada in 1962. By the time he returned to Ceylon 25 years after he had last seen it, he had become an important Canadian poet and novelist, with The Dainty Monsters (1967), The Man With Seven Toes (1969), The Collected Works of Billy the Kid (1970), Rat Jelly (1973), Coming Through Slaughter (1978), There’s A Trick With A Knife I’m learning To Do (1979).

The establishment of that country, following its readership, recognized his work with the Governor General’s Award more than once.

Ondaatje had probably become part of the well known Canadian ‘mosaic’ in which a variety of cultures co-exist, inextricably mingled, yet not homogeneous. Merged but not fused. Not the melting pot kind. And inside Ondaatje himself this could well be the kind of formation that has taken shape.

In The English Patient there are four loners, one is an Indian, two are Canadians and the third, the patient who is not recognizable, who may or may not be English. I was attracted to this in association with Ondaatje’s identity.

Ondaatje possibly demonstrates, (but does not claim) through his writing that this kind of open identity is more creative in exploring the human condition.

“I came to hate nations. We are deformed by nation-states. …….All of us, even those with European homes and children in the distance, wished to remove the clothing of our countries… we disappeared into landscape….Erase nations!”

Against such an identity background I read Anil’s Ghost as a progressive development emerging from Running in the Family.

Anil’s Ghost ( 2000) may be described as a novel in which “…Buddhism and its values met the harsh political events of the twentieth century” . This theme is developed through a story line about Anil Tissera, a UN sponsored female forensic scientist, who is allowed, reluctantly, by the government of Sri Lanka to investigate alleged human rights violations. She was born and bred in Sri Lanka and departed, as a young woman, to be educated abroad and to become Euro-American. Her foreignness is nearly complete. In her investigation she is paired off by the government with a 40-year old Sri Lankan archaeologist, Sarath Diyasena. The government’s apparently deliberate mismatch of archaeologist and UN forensic scientist then becomes a paradoxical match, between terrible contemporary events and one of the ancient traditions of the island, Buddhist civilization.

While working on Running in the Family Ondaatje could well have found that post-colonial privileged Sinhalese families, even allowing for professed Buddhist culture, could easily be merged in the imagination with colonial Burgher families .When Anil Tissera (“Ondaatje”) returns 18 years after Running in the Family there are only a few scattered relatives. Yet social silhouettes, from the first work keep running through Anil’s Ghost .

Like Michael Ondaatje in Running in the Family, Anil Tissera the returned “foreigner” in Anil’s Ghost uses a colonial remnant of the Colombo harbour, the cabin of an abandoned ship, the Oronsay of the old days of the Orient Line, to investigate unearthed skeletons. On her last morning in Sri Lanka she too leaves from there, though through virtue of plot and changed circumstances, the feelings are different:

“She wanted openness and air, didn’t want to face the darkness in the hold…there was no wish in her to be here anymore…be ready to leave at five tomorrow morning. There’s a seven o’clock plane.”

“I arrived in a plane but love the harbour” says Ondaatje in Running in the Family. He does not need to say he left, long ago, from the harbour. This connection of the area of the harbour as base, is organic, like many other relationships between the two works.

Running through Anil’s Ghost is a silhouette of the family in Running in the Family. Sarath Diyasena’s father made the family fortunes go up and down as Ondaatje’s father did in ‘Running’, the mother of the Diyasena boys was a dancer, in her youth, who wanted to choreograph them all, like Ondaatje’s mother in his earlier work. There was in the Diyasena family too an uncle who directed amateur theatricals, St. Thomas’ College by the sea is the college also of the Diyasena brothers. Ondaatje himself is silhouetted in Anil Tissera:

“Suddenly Anil was glad to be back, the buried scenes from childhood alive in her… As a child in Kuttapitiya Anil had once stepped on the shallow grave of a recently buried chicken… Her weight pushed the air in the body through the beak and there was a muffled squawk which frightened Anil.”

Ondaatje’s childhood home in Kuttapitiya, his father’s tea estate bungalow, features in ‘Running’.

I read all these connections between the two works, also as Anil (“Ondaatje”) continuing his research , now beyond the family into larger society, by holding on to, even if minimally, the identities he had discovered earlier, in Running in the Family.

( For the full version of this article, This essay was written for Prof. Ashley Halpe’s memorial volume)

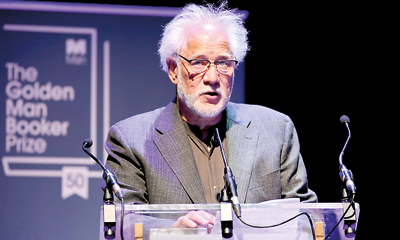

| Man Booker @50 picks ‘The English Patient’ as best

All 51 previous winners were considered by a panel of judges, who whittled them down to one from each decade. The public then voted on their ultimate favourite and settled on Ondaatje’s romance, which was originally a joint winner of the 1992 prize. Judge Kamila Shamsie said it was “that rare novel which gets under your skin”. Accepting the award, Ondaatje said: “Not for a second do I believe this is the best book on the list – or any other list that could have been put together of Booker novels.” He also said he suspected the Oscar-winning adaptation starring Ralph Fiennes, Juliette Binoche and Kristen Scott Thomas “probably had something to do with the result of this vote”.

| |

Sri Lankan-born Canadian author Michael Ondaatje’s book ‘The English Patient’ won the Golden Man Booker Prize at a festival to mark the literary award’s 50th anniversary.

Sri Lankan-born Canadian author Michael Ondaatje’s book ‘The English Patient’ won the Golden Man Booker Prize at a festival to mark the literary award’s 50th anniversary.