Sunday Times 2

China investments and Lanka’s growth: Areas of concern

- Sri Lanka was a major recipient of loans and investments from China during 2005-2014

- Between 2005-14 China official development assistance and investments were equivalent to 42% of the total public investment during the period

- During 2005-2014, Chinese received contracts worth USD 9.0 billion, which was equivalent to 76 percent of the total development assistance

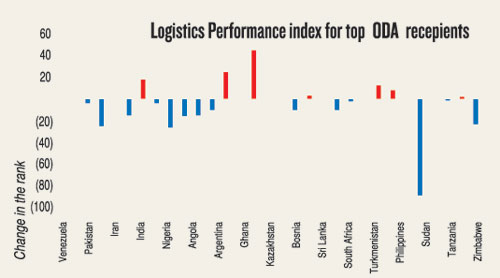

- Supported by China investments, Sri Lanka improved in Logistics Performance Index from 92 to 89 between 2007 and 2014

- The country declined 16 positions from 67 to 83 between 2005 to 2014 in the Corruption Perception Index

- Zimbabwe was able to negotiate better grant elements on Chinese loans compared to Sri Lanka

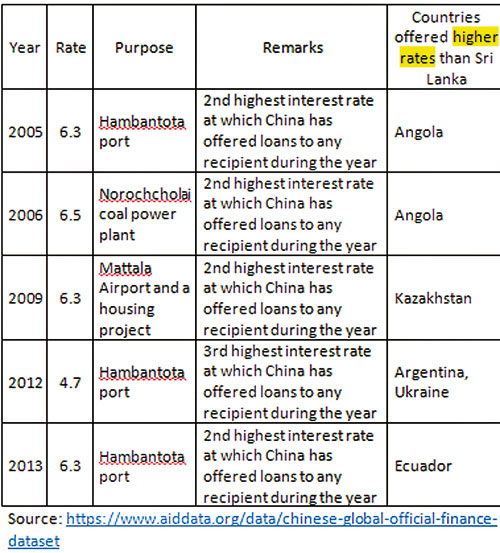

- Some of the loans received by Sri Lanka had very high interest rates in the world during this period

China announced its “Go Global” strategy in 2000. This strategy was a key focus in both the 10th Five Year Plan (2001-2005) and the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2006-2010). In line with the strategy beginning in the mid-2000s, China’s State-Owned Companies (SOCs) stepped up offering financing on a large scale to recipient countries along with foreign direct investments (FDI). According to the China Global Investment Tracker (http://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/), the value of China’s overseas investment and construction combined was USD 1.8 trillion between 2005 and 2017 from an insignificant volume prior to 2005. This is in addition to USD 705 billion offered in Chinese official development finance between 2000-2014, according to AidData’s Global Chinese Official Finance Dataset (https://www.aiddata.org/data/chinese-global-official-finance-dataset).

The Hambantota Port: Built with Chinese funds

With the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the focus has been shifted to international and maritime infrastructure. Chinese firms have pledged billions of dollars to develop maritime ports and related projects across the Indo-Pacific region since the announcement of the BRI, to increase global trade connectivity. Although the Chinese government portrays that these investments create win-win economic opportunities for all nations, there have been questions whether these investments are actually driven by strategic interests rather than economic rationale. Moreover, some authors argue that Chinese funding, which generally come without strings attached – other than requiring a Chinese company to receive the contracts, lead to debt traps. A commonly cited example, unfortunately, is the development of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota District (https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/25/world/asia/china-sri-lanka-port.html) by China.

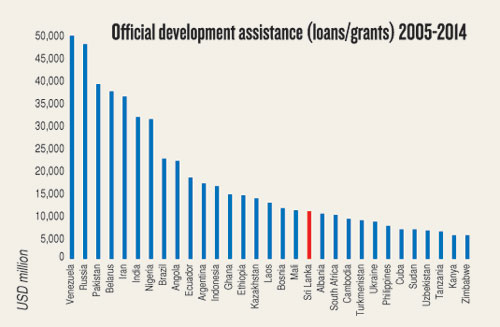

Sri Lanka was a clear beneficiary of China’s “Go Global” strategy related fund flows. The country ranked among the top 20 recipients of Chinese official development assistance (ODA) with USD 11.8 billion of ODA and other investments flowing in during 2005-2014. This amount was equivalent to 42 percent of the total public investment during the same period. In addition to ODA and other investments, China started engaging in large scale construction contracts, especially during the post-war construction drive. During 2005-2014, Chinese companies received contracts worth of USD 9.0 billion, which was equivalent to 76 percent of the total ODA value.

Sri Lanka was a clear beneficiary of China’s “Go Global” strategy related fund flows. The country ranked among the top 20 recipients of Chinese official development assistance (ODA) with USD 11.8 billion of ODA and other investments flowing in during 2005-2014. This amount was equivalent to 42 percent of the total public investment during the same period. In addition to ODA and other investments, China started engaging in large scale construction contracts, especially during the post-war construction drive. During 2005-2014, Chinese companies received contracts worth of USD 9.0 billion, which was equivalent to 76 percent of the total ODA value.

The terms negotiated by Sri Lanka were not attractive. It appears that the urgency of funding and the limited feasibility of the project have taken a toll on the interest rate. Some of the negotiated interest rates do not reflect relative credit ratings of respective countries. For example, Sri Lanka’s interest rates were higher than those of Venezuela and some African countries with lower credit ratings. A few examples are given in the table below.

More importantly, the grant element — computed based on the interest rate, repayment profile, face value and a discount rate — was also indicative of unfavorable terms for Sri Lanka. In certain instances, African countries including Zimbabwe could negotiate better terms reflected in higher grant elements compared to Sri Lanka.

More importantly, the grant element — computed based on the interest rate, repayment profile, face value and a discount rate — was also indicative of unfavorable terms for Sri Lanka. In certain instances, African countries including Zimbabwe could negotiate better terms reflected in higher grant elements compared to Sri Lanka.

Note: The grant element measures the concessionality of a loan. It is defined as the difference between its nominal value (face value) and the sum of the discounted future debt-service payments (net present value) to be made by the borrower, expressed as a percentage of the face value of the loan. Whenever the interest rate charged for a loan is lower than the discount rate, the resulting present value of the debt is smaller than its face value, with the difference reflecting the grant element of the loan.

In theory, large infrastructure investment should improve infrastructure, accelerate growth, and create more jobs for people. Accordingly, Chinese financing appears to have helped Sri Lanka to climb the Logistics Performance Index of the World Bank, albeit marginally, from 92 to 89 between 2007 and 2014. Sri Lanka’s economic growth also accelerated, in particular, during the early years of the post-war period, with construction contributing to 16 percent of the total growth between 2010 and 2014. However, there has been a deceleration of growth subsequently, partially explained by the impact of inclement weather, along with the deceleration of the contribution to growth from the construction sector. Other sectors have not been able to provide a boost to growth in a substantial way, supported by improved logistics and infrastructure of the country, as theory expects.

In theory, large infrastructure investment should improve infrastructure, accelerate growth, and create more jobs for people. Accordingly, Chinese financing appears to have helped Sri Lanka to climb the Logistics Performance Index of the World Bank, albeit marginally, from 92 to 89 between 2007 and 2014. Sri Lanka’s economic growth also accelerated, in particular, during the early years of the post-war period, with construction contributing to 16 percent of the total growth between 2010 and 2014. However, there has been a deceleration of growth subsequently, partially explained by the impact of inclement weather, along with the deceleration of the contribution to growth from the construction sector. Other sectors have not been able to provide a boost to growth in a substantial way, supported by improved logistics and infrastructure of the country, as theory expects.

Beginning from the mid-2000s, Sri Lanka has suffered a setback in the Corruption Perception Index of Transparency International. The country declined 16 positions from 67 to 83 between 2005 and 2014 which coincides with a period of substantial funding coming from China. Moreover, Sri Lanka’s illicit financial outflows during the same period (2005-2014) could be estimated at USD 13.0 billion (the range being USD 9.2 to 16.2 billions) based on the mid-point outflows published by the organisation for Global Financial Integrity. While the present analysis does not provide evidence of the causality between Chinese funding and corruption/illicit financial flows, the recent investigative article in New York Times on Hambantota port is suggestive of Chinese funding going to Sri Lanka’s presidential election campaign in 2015.

Beginning from the mid-2000s, Sri Lanka has suffered a setback in the Corruption Perception Index of Transparency International. The country declined 16 positions from 67 to 83 between 2005 and 2014 which coincides with a period of substantial funding coming from China. Moreover, Sri Lanka’s illicit financial outflows during the same period (2005-2014) could be estimated at USD 13.0 billion (the range being USD 9.2 to 16.2 billions) based on the mid-point outflows published by the organisation for Global Financial Integrity. While the present analysis does not provide evidence of the causality between Chinese funding and corruption/illicit financial flows, the recent investigative article in New York Times on Hambantota port is suggestive of Chinese funding going to Sri Lanka’s presidential election campaign in 2015.

As a case study, Chinese funding in Sri Lanka could offer a few lessons to the world. First, while ODAs and investments are important for a country’s progress; projects, which are not matured enough in terms of feasibility and preparation, could lead to unintended consequences. In such cases, the recipient will be in a weak position to engage in negotiations, thus leading to unfavorable terms. Second, maturity mismatches could result in liquidity crisis, which requires loan restructuring or forfeiture of the infrastructure asset in favour of the financier – Hambantota port asset provides a good example. More importantly, these projects could offer high rates of economic growth during the period of the construction; however, with limited benefits accruing to the economy thereafter, growth sustainability becomes a cause for concern.

As a case study, Chinese funding in Sri Lanka could offer a few lessons to the world. First, while ODAs and investments are important for a country’s progress; projects, which are not matured enough in terms of feasibility and preparation, could lead to unintended consequences. In such cases, the recipient will be in a weak position to engage in negotiations, thus leading to unfavorable terms. Second, maturity mismatches could result in liquidity crisis, which requires loan restructuring or forfeiture of the infrastructure asset in favour of the financier – Hambantota port asset provides a good example. More importantly, these projects could offer high rates of economic growth during the period of the construction; however, with limited benefits accruing to the economy thereafter, growth sustainability becomes a cause for concern.

Note: This article was prepared based on publicly available information. The choice of the period covered in the present analysis was not based on political considerations, but on data availability. ODA dataset covered the period from 2001 to 2014 while investment and contract related dataset was available for 2005 to 2017. Corruption Perception Index has its historical series. Illicit Financial Flows covered the period 2005-2014. Logistics Performance Index was originated only in 2007. Given the data considerations, mainly on ODA, contracts and investment, the overlapping period of 2005-2014 was considered.

| Who got what? Official development assistance Venezuela has been the largest recipient of China’s official development assistance from 2005 to 2014. While the top five include Russia, Belarus, Pakistan and Iran in addition to Venezuela, Sri Lanka was among the top 20 countries receiving Chinese official development assistance during this period.Note: AidData’s Global Chinese Official Finance Dataset includes loans, export credits, technical assistance and other types of support such as scholarships to public officials. The donor’s country, China, is no exception. While there are many occasions in which Chinese companies have been able to win contracts world over, Chinese official development assistance appears to have clear links with contract execution. In Sri Lanka, the total contract value offered to Chinese companies between 2005 and 2014 was equivalent to 77 percent of the total Chinese official development assistance. Logistics performance and corruption perception | |