Lankan economy fails continuously

The Annual Report of the Central Bank (CB) of Sri Lanka for the year of 2017 confirms that despite new economic policy measures, the economy is failing in many vital aspects if not in entirety. Main objectives of the government as manifested during the past three and a half years include accelerated economic growth at 7 per cent, one million new employment, eradication of debt burden, industrial development, increase of FDI inflow, export promotion, eradication of poverty and accelerated infrastructure development, etc. There have been several development policy documents presented to Parliament by the Prime Minister and several policy measures have been taken by the National Economic Development Council to re-rail the economy which was said to have been de-railed during the previous regime. This was supported by four reshuffles introduced to the Cabinet during the period.

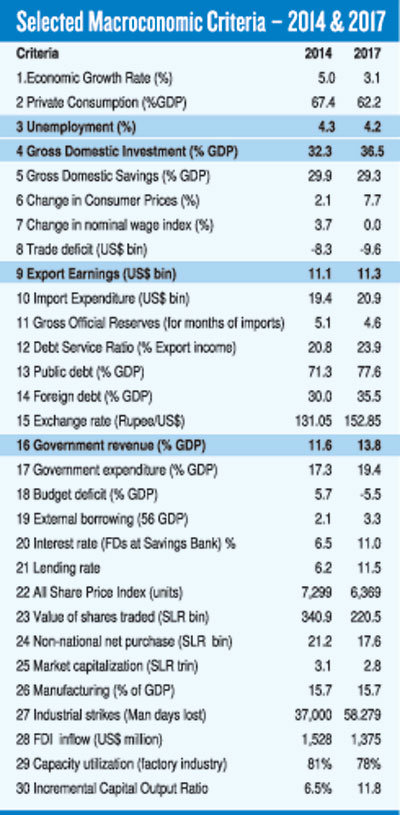

The performance of the economy and the success or failure of the government’s role in maneuvering the economy is presented in reports released by the CB. The CB’s annual reports during the past two years have confirmed that the economy is performing poorly. This article compares and contrasts the state of the economy in 2017 with that of 2014 in order to approximate the direction and performance of the economy. Among the 30 different criteria presented in this table, only four have shown slight progress whereas 26 have failed in contrast to their values in 2014. As this is a mere continuation of failure since 2015, this article analyses economic implications of the four improved areas instead of describing those 26 areas lagging behind.

The improvement of unemployment rate from 4.3 per cent in 2014 to 4.2 per cent in 2017 indicates a progress of 0.1 per cent during a three year period. This comprises a large portion of recruitment into government service. As the job market has shrunk due to growth contraction, new employment opportunities have not been generated in the private sector to a satisfactory level. The growth contraction is mainly due to decrease in private consumption and poor exports. Unsatisfactory job creation has withered the one million job creation programme. The much expected employment opportunities from FDI and foreign employment also have dwindled due to falling FDI inflows and failure to harness foreign employment opportunities.

Government revenue has improved from 11.6 per cent to 13.8 per cent during the three year period. This is due to widened and deepened tax net. On the contrary this transfers money from individuals and industry. Thus increase in government revenue through tax income has an adverse repercussion on consumption. This causes decrease in private consumption in the first round and leads to accumulation of inventory and production cut down which curtails factor income causing contraction in national income. As the government’s expected income drops due to economic contraction, it tends to widen and deepen the tax net in the second round to increase income or otherwise fills overall deficit through inflationary sources. As this cycle deepens a vicious circle of economic depression and inflation are experienced. The continuous decrease in GDP from 5 per cent in 2014 to 3.2 per cent in 2017 and 2 per cent in the first quarter of 2018 can partly be appropriated to this phenomenon. However, if the government spent tax revenue to generate new revenues, then this process is cancelled out and GDP is recuperated. Government expenditure has increased by 2.1 per cent while state revenue has increased by 2.2 per cent during 2017. This increase in expenditure was mainly due to uneconomical projects that do not generate new incomes. As there seems to be an expansion in the budget deficit of Rs. 733 billion this year which requires financing through loans or other means that eventually causes tax or price increase during the year.

The increase of gross domestic investment (GDI) from 32.3 per cent to 36.5 per cent during this period is remarkable. According to theory, there should be an ascending relationship between GDI and GDP growth rate. However, contradictorily, the descending relationship between the two has been reported; GDP growth rate has decreased from 4 per cent in 2016 to 3.2 per cent in 2017 while GDI has increased significantly. The relationship between GDI and GDP is explained by the concept of Incremental Capital Output Ratio (ICOR). This measures the units of capital required for a unit of growth in GDP. In 2017, this ratio has been 11.7:1. That is 11.7 units of investment are required to generate one unit of economic growth. In Sri Lanka, throughout the past decades this ratio has been generally 5:1 i.e. five units of investments bring about one unit of GDP growth. The government expects 7 per cent of economic growth in the coming years. According to ICOR calculation for 2017, there should be 82 per cent of GDI to gain 7 per cent of economic growth which is beyond imagination.

Export earnings have marginally grown by 1.8 per cent from Rs. 11.1 billion to Rs. 11.3 billion during the 3-year period which in other words is a US$ 70 million average increase per year. This growth should be seen in the context of the rapidly depreciating rupee during the period. It is believed that depreciating local currency is helpful in boosting exports. Sri Lanka’s exchange rate against US$ has depreciated by almost 30 rupees or by 20 per cent during the period. If exports were stimulated due to rupee depreciation at this rate, export earnings could have soared by US$ 2.2 regardless of new exports if any. This suggests that the government has failed in its export promotion drive together with FDI led export promotion. Although FDI has picked up in 2017, it has not contributed significantly to boosting exports. This encourages us to conclude that new FDI has focused more on local market than export market which is less advantageous.

The above discussion reveals that the four indicators, out of 30 as indicated in the above table, that have shown progress since 2014 also have encountered macroeconomic complications. The economy has become almost numb and thus irresponsive to policy measures introduced since 2015. This ailment of the economy can be observed from several symptoms. They include irresponsiveness of output to increasing domestic investment, irresponsiveness of exports to increasing FDI, irresponsiveness of exports and imports to depreciating rupee, and irresponsiveness of the production system to increased government expenditures. Additionally, hyper sensitivity in sections of the economy has caused several problems which include increase in cost of production due to increase in factor costs, decrease in real consumption due to taxes and increasing consumer prices, and the vicious cycle of tax. In general, the performance of the economy in 2017 is mostly a continuation of policy failure since its onset in 2015.