Columns

Economic implications of New York Times expose: Infrastructure development and foreign debt

View(s):The New York Times (NYT) expose of June 25, 2018 on the country’s high foreign indebtedness to China has once again drawn attention to the high cost of borrowing from the Chinese and the country’s debt servicing burden.

It alleges that there was a great deal of kickbacks and corruption. Consequently the country’s indebtedness to China increased and resulted in Sri Lanka being in a debt trap. Former President Mahinda Rajapaksa has denied the NYT claims of corruption and threatened to sue the paper.

It alleges that there was a great deal of kickbacks and corruption. Consequently the country’s indebtedness to China increased and resulted in Sri Lanka being in a debt trap. Former President Mahinda Rajapaksa has denied the NYT claims of corruption and threatened to sue the paper.

Chinese debt

In this renewed interest in infrastructure investment and development, it is apt to discuss the economics of the massive infrastructure investment undertaken by the Rajapaksa regime. The NYT contends that the high cost infrastructure expenditure of the previous government funded by the Chinese has created a massive indebtedness to China.

Pertinent economic issues

Has the infrastructure investment and development led to a significant economic benefit? Has it increased the foreign debt to massive proportions and led the country into a foreign debt trap? What were the merits and defects of the investment programme of the last regime?

The pertinent issues are: Whether these infrastructure developments were beneficial; were they too costly, and was the extent of foreign indebtedness beyond the capacity of the Government to repay? In other words, was the cost of the infrastructure development too high, were the priorities in infrastructure appropriate and correct and was the debt incurred too much?

Infrastructure improvement

There can be no doubt that the previous regime improved the country’s infrastructure as never before. The post independent period was largely one of living on the infrastructure developed by the British before independence. Roads, especially outside the metropolis, bridges, railway and ports were developed by the Rajapaksa regime, especially after the end of the war in 2009.

Economics of infrastructure

Intrinsically, infrastructure projects have high costs and their economic returns are over a long period of time. Owing to the long gestation period and their low annual returns, it is prudent for infrastructure investments to be phased out, rather than undertaken concurrently in large measure.

Furthermore, when infrastructure projects are foreign funded, foreign indebtedness could rise sharply if these infrastructure projects do not increase tradable goods or only increase exports marginally, as it happened with these investments. They then increase the country’s debt and make foreign debt servicing onerous. Moreover, owing to other policies of the Rajapaksa regime, such as the withdrawal of the GSP plus concession by the European Union (EU), exports declined. In contrast, had the large investment been in export manufacturing industries, the export income derived after its shorter gestation period would have reduced the debt servicing burden.

White elephants

White elephants

To make matters worse, apart from the justifiable infrastructure projects such as the improvement of the road and railway network and bridges, there were large investments in projects that did not bring returns and even incurred additional costs of maintenance. These white elephants included the Hambantota harbour, the Mattala airport and the Hambantota cricket grounds. These and the wide roads built in remote areas like Hambantota were projects with low or no returns. As it turned out they became a financial burden to the subsequent government that had to find ways and means of making them bring in some returns.

Corruption

The New York Times article had serious charges of corruption. If the allegations of corruption are correct, then the costs of these projects would have been higher than warranted. It has been suggested that the kickbacks cost 20 percent more and therefore the cost of the projects and economic burden more.

Former President Mahinda Rajapakse has denied these allegations and is challenging the NYT. The truth may, however, be never known,

Growth of foreign debt

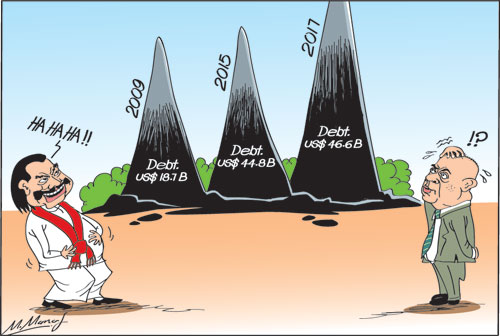

Foreign debt increased significantly from 2000-2009 that were war years. It doubled from US$ 9 billion in 2000 to US$ 18.66 billion in 2009. In the next five years it more than doubled, and at the end of 2014 foreign debt had risen to US$ 42.9 billion or 53.6 percent of GDP.

The high costs of the infrastructure were a major reason for this increase in debt, though not the only one. The indebtedness was not only to the Chinese. There were substantial borrowing from multilateral agencies and international banks. In fact, the debt to China is said to be only a small fraction of the total foreign debt.

Fundamental flaw

A fundamental deficiency in these high cost foreign funded projects was that they did not increase the country’s tradable goods and increase exports. Therefore, they did not ease the debt servicing costs. It is due to this factor that while GDP increased owing to the infrastructure investment, the trade deficit continued to expand instead of shrinking. While the annual average GDP growth increased by 6 percent during 2010-15, the trade deficit expanded.

Foreign debt increases

The country’s foreign debt has continued to increase in the last three years under the new Government. At the end of 2015 the foreign debt reached US$ 44.8 billion or 54.4 percent of GDP. By the end of 2016, it reached US$ 46.6 billion and expanded to US$ 51 billion at the end of 2017 — that is estimated at about 55 percent of GDP.

Although debt repayments was one reason for increasing foreign borrowing in the last two years, the economic policies pursued by the unity government too contributed to the need to borrow. Inappropriate monetary and fiscal policies aggravated the problem by increasing the trade deficit.

All things considered

Although many infrastructure projects made important contributions to the country’s economic development, there were several projects that had no economic justification and proved to be white elephants. The large foreign funded investment did not increase the country’s export earnings significantly and therefore enhanced the debt servicing costs.

Quite apart from the issue of corruption that is being challenged by the former President Mahinda Rajapaksa, there is no doubt that the infrastructure development were very costly and increased the country’s foreign debt burden. Owing to the need to repay the debt as well as other expenditure that was foreign funded, the debt increased between 2015 and 2017.

In conclusion

The servicing of the debt is a severe problem for the government. Debt servicing costs are estimated at US$ 4.2 billion in 2019 and are estimated to be US$ 12 billion in the next three years. The international borrowing for infrastructure development is one reason for aggravating this problem.

Leave a Reply

Post Comment