Sunday Times 2

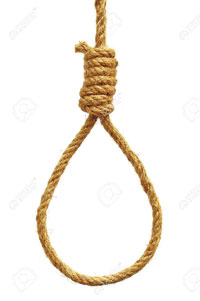

Enforcing the death penalty: A violation of national and international law

The reports in recent newspapers that President Sirisena “will commence signing death warrants”, and that the prisons authorities had been requested to send him nineteen names of death-row prisoners who are dealing in the drug trade while in prison, raise serious legal issues of a national and international nature.

These issues have apparently been ignored by members of the Cabinet who enthusiastically endorsed the President’s desire to have nineteen persons hanged. This is yet another example of populist, emotion-driven, decision making at the highest levels of government that pays scant regard to empirical evidence and to obligations imposed by law, both national and international.

These issues have apparently been ignored by members of the Cabinet who enthusiastically endorsed the President’s desire to have nineteen persons hanged. This is yet another example of populist, emotion-driven, decision making at the highest levels of government that pays scant regard to empirical evidence and to obligations imposed by law, both national and international.

The constitutional obligation

The last judicial execution took place in 1976 when I was Permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Justice. Then, as now, the Constitution prescribed the procedure to be followed when an accused person was sentenced to death by a trial court. Article 34 of our present Constitution states that, following the imposition of such sentence, the President shall cause a report to be made to him by the trial Judge. He shall forward such report to the Attorney General for his advice. Thereafter, the President shall send both reports to the Minister of Justice who will make the final recommendation whether the sentence should be carried out or whether it should be commuted to life imprisonment. When the President acts on that advice, and makes the appropriate order, the case is closed.

The procedure followed when Mr Felix Dias Bandaranaike was Minister of Justice was prescribed in a ministry standing order. If either the trial Judge or the Attorney General had recommended that the sentence should not be carried out, the Minister advised that the sentence be commuted. If the trial Judge and the Attorney General had both recommended that the sentence be carried out, a senior assistant secretary examined the case record and the investigation notes for one of three elements: (i) evidence of premeditation (ii) excessive cruelty in the commission of the murder (iii) any other material that “shocks the conscience”. If one of these elements was present, the Minister advised the President to let the law take its course. The executions ceased in 1976 when “Maru Sira” was found not to have been judicially executed. On 22 May 1977, the fifth anniversary of the Republic, President Gopallawa commuted the sentences of everyone on death row: 144 men and 3 women. Thereafter, President Jayewardene and his successors in office commuted every sentence of death. None, unfortunately, initiated legislative action to remove the death penalty from the statute book.

Legal issues

If the present Minister of Justice had conscientiously performed her constitutional duty, and if the President had acted according to the policy followed by his predecessors for 42 years, there would be no prisoners today under sentence of death. They would all be serving life sentences. A prisoner serving a life sentence cannot now be hanged. On the other hand, if there are prisoners still lingering in death row, nineteen among them cannot now be identified for hanging (as reported in the newspapers), because that suggests that the reporting procedure in respect of them, as required by the Constitution, has not yet been performed. If that be the case, and since the President has already publicly declared his desire to have them hanged, any recommendation submitted by the Minister to give effect to the President’s desire will surely be challenged in court as having been influenced by irrelevant considerations. The Minister would not have brought to bear her own independent judgment as required by the Constitution but would instead have been influenced by the President’s publicly declared desire and, indeed, by the Cabinet decision too.

Another issue arises from the reason publicly declared by the President for his desire to have the prisoners hanged, namely, that they have been indulging in the drug trade from within the prison premises. That cannot be the basis for an execution order. None of them has yet been indicted or convicted of the offence of drug trafficking from within prison premises. A prisoner has first to be charged with that offence, convicted and sentenced to death by a court, had his appeal dismissed, and then been recommended for execution by the Minister of Justice before the President can sign his or her death warrant. Any other course of action will constitute extra-judicial murder.

Empirical evidence

There is now an international commitment to abolish the death penalty. This is not only because of the desire to respect the dignity of the human being and the sanctity of human life, but also because the global empirical evidence demonstrates beyond any shadow of doubt that the death penalty does not serve as a deterrent. The most effective deterrent to crime is the certainty of detection. Competent policing, efficient prosecution, and expeditious trial – none of which appears to be evident in Sri Lanka today – should be the primary objective of the government. If, in the absence of such deterrent, an individual proceeds to a life of crime, the progress that humanity has made through the centuries now demands that that individual be afforded an opportunity for rehabilitation, for reform, for repentance, for hope, for spiritualty, so that some day he or she may be able to enjoy those fundamental rights and freedoms which others outside the prison walls enjoy, but which are only possible if his or her right to life is not extinguished.

The international consensus

The Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights requires that no one shall be executed and that each State shall take all necessary measures to abolish the death penalty within its jurisdiction. In 1983, the Council of Europe abolished the death penalty in peacetime, and in 2002 abolished the death penalty in all circumstances, including wartime. Similar instruments have been adopted by the states parties to the American Convention on Human Rights. In 2014, the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights developed a protocol on the abolition of the death penalty. More than 160 of the 193 member-states of the United Nations have abolished the death penalty or introduced a moratorium, either in law or in practice. They include all the countries of Europe including Russia, nearly all the countries of Africa, and all the countries of South and Central America and Canada, as well as Australia, New Zealand and much of the Pacific.

If Sri Lanka now breaks its 42-year moratorium on executions, it is inevitable that economic concessions granted by the European Union including GSP+ will be withdrawn. Assistance from abroad in the investigation of crime may not be forthcoming. Requests by Sri Lanka for the extradition of persons awaiting trial or already tried and convicted will probably be refused by other States because of the unpredictability of the sentencing policy of the Government. Many beyond our shores who truly and faithfully adhere to the philosophy of life based upon tolerance and compassion as expounded by the Buddha will stand aghast as the Government of the only country in the world whose Constitution requires the State “to protect and foster the Buddha Sasana” addresses a human being confined to a prison cell and tells him or her: “You are beyond the pale of humanity. You are not fit to live among humankind. You are not entitled to life. You are not entitled to dignity. You are not human. We will therefore annihilate your life”.

The unseen reality

When President Sirisena sits at his desk and picks up his pen to sign a death warrant ordering the Commissioner of Prisons to hang a human being by his or her neck until he or she is dead, I would entreat him to read to himself the execution of the death penalty as described by Professor Chris Barnard:

“The man’s spinal cord will rupture at the point where it enters the skull, electro-chemical discharges will send his limbs flailing in a grotesque dance, eyes and tongue will start from the facial apertures under the assault of the rope and his bowels and bladder may simultaneously void themselves to soil the legs and drip on the floor”.

If that has had no effect and the deed has been done, the members of the Cabinet who authorized the President to revoke the 42-year old moratorium, and the Roman Catholic Cardinal and Buddhist monks who cheered him on, should perhaps reflect on the following words of a former Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court of the Republic of South Africa:

“The deliberate annihilation of the life of a person systematically planned by the state as a mode of punishment is not like the act of killing in self-defence, an act justifiable in the defence of the clear right of the victim to the preservation of his life. It is not performed in a state of sudden emergency, or under the extraordinary pressures which operate when insurrections are confronted or when the state defends itself during war. It is systematically planned long after – sometimes years after – the offender has committed the offence for which he is to be punished, and while he waits impotently in custody, for his date with the hangman. In its obvious and awesome finality, it makes every other right, so vigorously and eloquently guaranteed by the Constitution, permanently impossible to enjoy. Its inherently irreversible consequence makes any reparation or correction impossible, if subsequent events establish, as they have sometimes done, the innocence of the executed individual or circumstances which demonstrate manifestly that he did not deserve the sentence of death.”

(The writer was one-time Secretary to the Ministry of Justice)