An insider goes to the heart of a kingdom

The Kandyan kingdom has always intrigued; from Robert Knox of the 17th Century down to this day when you cross the ancient boundaries of the Uda-rata or amble around the shady lake, with regal buildings rising from the green hills forming an amphitheatre. Kandy is an enigma with its lofty aristocratic traditions and culture. Only a true son of the land could envision a full-blooded picture of this last stronghold of the Sinhalese monarchy.

The Kandyan kingdom has always intrigued; from Robert Knox of the 17th Century down to this day when you cross the ancient boundaries of the Uda-rata or amble around the shady lake, with regal buildings rising from the green hills forming an amphitheatre. Kandy is an enigma with its lofty aristocratic traditions and culture. Only a true son of the land could envision a full-blooded picture of this last stronghold of the Sinhalese monarchy.

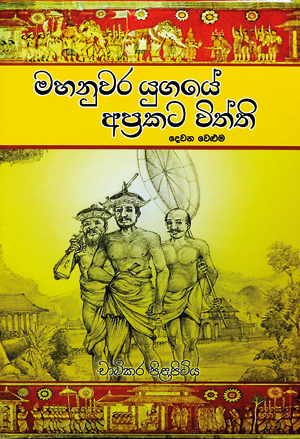

Chamikara Pilapitiya’s genealogy can be directly traced back as far as 1592 when Wimaladharmasuriya the First was king of Kandy. Chamikara has had a passion for history from his young days at Trinity College. His book Mahanuwara Yugaye Aprakata Witti is the fruit of ten years’ hard labour, in the course of which he unearthed a good number of unpublished primary sources- sannas or royal grants, ola leaf histories, and works of poetry- found in old homes and temples. He would salvage manuscripts destined to dusty oblivion in libraries and museums here and abroad- including in New York, Russia, Amsterdam and London.

When Chamikara’s father, Ariya Sumana Bandara, was on his deathbed, as tradition dictated he imparted family lore to him as the youngest son of the family. These included old Kandyan military secrets as well as secrets regarding the family lineage: enough to intrigue and fire the young man to embark on a quest into the heart of unknown Kandy. The quest, which would take him to many faraway places, would gather enough material for two magisterial volumes, a work justifying long days snatched off holidays from the tea industry- and precious family time: searching for lost tunnels in thick jungle, tracking ola manuscripts in ancient vihares, or braving wild mountains to locate old beacons and fortresses. In all the ventures his immaculate ancestry opened for him doors that would otherwise have been locked with those typically gigantic temple keys.

The book is testimony to the fact that a lot of valuable material, written records as well as oral traditions, remain locked in the pettagamas and libraries of Kandyan temples and houses as well as in the memories of its monks and nobility.

Chamikara’s passion for firearms and military history has obviously been a catalyst in pulling him into this research- the history of the kingdom being full of epic battles fought in dramatic hill terrain with classic and ingenious strategies and intriguing firearms- a great range from native to European armament. So the book is scattered with ‘profiles’ of guns- from the first Sri Lankan cannons to artillery guns used in the First World War.

The book is also a Kandyan Almanach de Gotha of sorts where many important families appear, tracing the evolution of the Kandyan nobility as courtiers of Sinhalese kings, then under the Nayakars, and consequently emerging as part of a new English-educated local elite under the British.

Also recorded in it is a grand story of the East meeting the West; where the indigenous landscape slowly gives way to advancing galleys and plate armour, heralding a new dawn. The two volumes come well illustrated though in black and white. Among the previously unpublished sketches and maps are a picture from the Netherlands, dating from 1766, of the Kandyan army on parade, and a map of the City of Kandy drawn by the Dutch during the invasion in 1765. Also produced in the book are the horoscopes of King Sri Wickrema Rajasinghe, his Queen Rengammal, the chatelaine Ehelepola Kumarihamy and Veera Puran Appu- warrior and freedom fighter.

Stitched onto the fabric of the book, which runs like a vivid mural of Kandy’s story till the Second World War, are gems of interchapters. These leaven the work with colourful insight into the age, on a range of subjects from the mukkaru, an ancient race probably of Arabic extraction who came here in search of precious stones, and the Bandaras, local chieftains who were later deified, to the great revivalist Buddhist monk Weliwita Saranankara Sangharaja. He hunts down King Raja Sinha II’s personal gun, with which he shot at an African mercenary who tried to kill him, and the nittewo, a fierce half-human pygmy race that is said to have inhabited the jungles of the Eastern province more than three centuries ago.

Of the final two extensive chapters, the first is on the Sacred Tooth Relic of the Buddha, the Diyawadana Nilame and the Dalada Maligawa, while the second chapter deals with the privileged circle of aristocratic families from which the Diyawadana Nilame is selected. Attached to the end of the book are a number of addenda on the illustrious Pilapitiya family.

The book is a meticulously researched academic work, but at the same time it is an exciting narrative you can dip into and be swept away by. The period it covers was one of high drama, and the saga, within each chapter, is broken down to snippets- each with its pithy title, so that the reading is lucid.

It was, also, a hugely dynamic age- so much change occurring in five centuries that makes the preceding millenia look a flatland of calm and peace in comparison. Yet woven into it also is personal history- not just of princes and courtiers and high personages but also of Corporal Barnesley who escaped the 1803 Kandyan wars with his almost severed head held in place with hands and lived to tell the tale- and the ‘young terrorist from Kegalle’, an innocent young man whose life was cruelly forfeited following the war of 1848, and his father killed in his attempts to save the son.

A hallmark of the early part of the period covered is the heavy inconsistency between local sources and the records left by the colonists. Chamikara, thanks to the unique vantage point he has gained with his research, is able to bring in a great degree of balance and accuracy into the midst of clashing narratives.

The work is also a rich collage of documents from the period: from the famous 1815 Kandyan Convention to the food rations granted to the king of Kandy held prisoner by the British, and the exquisite treasures that stately walawwes would yield to the colonists who kept records glittering with detail.

Whether as a reference book, that will sit easy on an erudite shelf, or as lighter reading, the book is a rare offering with new insight into a kingdom on the cusp of the Modern Age, divesting itself of the medieval. The fruit of the author’s sleuthing into the past will spill out on to two more publications, to appear soon, focusing on his passion for the military: The History of Sri Lankan Fire Arms, and The Secret Tunnels of Sri Lanka.